Worldbuilding can be a dull affair. An attempt to survey a place that isn’t there can often result in writing that isn’t readable. For M. John Harrison [1], a work of fiction relying on worldbuilding does not invite readers to the text with the idea that reading is a game in itself; it does not ask a reader to interpret, but to merely see or share a single world. This approach in speculative fiction produces text that functions as an operation manual and is patronizing to the reader. Like Harrison, I tend to see a heavy-handed stress on worldbuilding as a red flag. Writers—even notable ones—all too often fall prey to writing pages of exposition that can end up having no bearing upon the story or character.

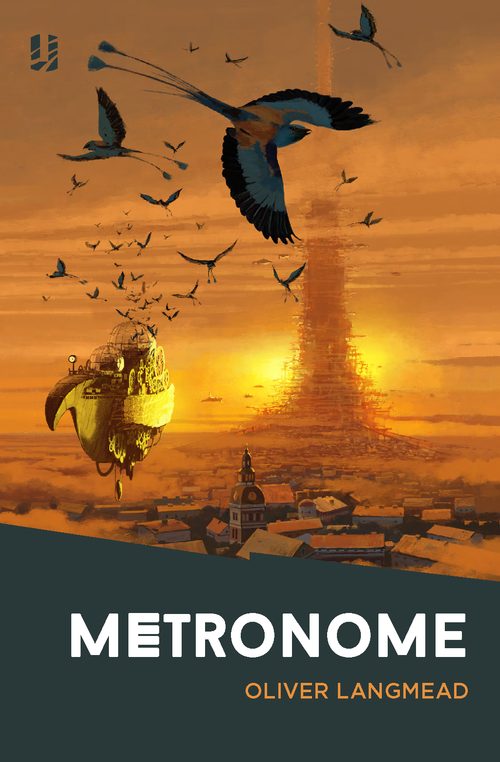

Oliver Langmead takes a risky route in his sophomore novel Metronome (Unsung Stories, 2017). His protagonist, William Manderlay is an aging musician living in a retirement home, suffering from arthritis. He can no longer play his instrument, and his age prevents him from sailing the seas as he had done in his youth. Manderlay is now being haunted by nightmares, which to his friends are signs of decay and senility. Manderlay’s dreams are not his alone. They are somewhat ‘shared,’ meaning that within these dreams, there are doors that connect dreamers, leading to a communitarian process that has over time resulted in a civilization centred around the city of Babel. This civilization is inhabited by dreamers, their figments, nightmares and Sleepwalkers. The last of this lot are responsible for hunting nightmares and keeping safe the Dreamworld. Metronome’s plot starts when one of these Sleepwalkers goes rogue, leading to a chase, where Manderlay’s music works as a map to a place where something ancient and sinister resides.

A large part of the story in Metronome takes place within the Dreamworld—which is a different world from the real world where Manderlay is dreaming.

Langmead is a proficient writer who manages to steer clear of the temptation to divulge the details of the world he has created all the time, curbing an enthusiasm that can otherwise debilitate the story. When Manderlay first enters the city of Babel (with its own tower), we are told how the centre of this dream-civilization has come to be. This amalgamation of dreams, which by all means should not exist, can be overwhelming for someone like Manderlay first walking through it. The plot therefore is never scrambled, and details do not pop up now and then at the cost of pace and coherence.

Langmead’s descriptions are vivid and beautiful:

Tall houses and teeming streets seem to have tumbled from its edges, as if they are fallen pieces of masonry, shadows made long by the golden sun. They sweep away on every visible side, made in all manner of different designs. The roads I can see are arranged haphazardly, as if spun by a careless spider, but in such a way that all of them seem to lead to the tower. There is no telling where the tower begins and the city ends, however, because the tower rises from the city gradually.

There are long slopes to every side of the city, some of which lead to distant plains and mountains, and some of which lead to crowded docks beside a glittering sea. I can see the black silhouettes of dozens of sailing ships, steam ships, tankers and all kinds of seafaring vessels.

And where he tells us about the dizzying sights of Babel:

I come to a tangled network of streets. They are filled with people and movement and sound. The crowds here are as much an assortment as the city they inhabit, treading the cobbles of the incline on heavy boots, sandals and even bare feet. I can hear conversations in European languages, and African, and Asian, with accents so varied that I struggle to even recognise English.

Where the streets open up and become roads, I travel past vehicles as well. Vans and cars rumble past, and so do tuk-tuks, bicycles and horse-drawn carriages. I am reminded of the chaos of the streets of Mumbai; with so many different vehicles the sight becomes confusing and dazzling.

Langmead is good at creating an arbitrary world which does not work by rules, where characters cannot always depend upon an assortment of powers (or magic) to make things work in their favor. This works to a great effect in the case of Sleepwalkers, who cannot use their powers to radically alter outcomes of events or to solve problems.

Using dreams in a story requires a cautionary approach in a manner that does drastically affect the implications of the plot.

The problem with Metronome is that Manderlay’s dreams do not tell us much about the characters. While Langmead does point out that Manderlay has been spending his last years fraught with longing and regret (and the dreaming in many ways works as a course correction), he does so through intrusive and abrupt flashbacks. Other characters are not given much place within the story, save for minor details about the motivations of a few.

Metronome would have been far more enjoyable if the Sleepwalkers were better sketched, but we meet the one that has gone rogue only twice, and while we are told about her objectives, her motivations are mostly left unstated. In her case, Langmead’s efforts to not use magic or powers as aplot device cease, as seen at a critical point in the story. Another fault with Metronome is that it tends to centre too much on Manderlay – his regrets, memories, and longing for a past that sometimes gets close to escapism. This especially affects the ending, which works against what was otherwise an intriguing buildup; the revelation or resolution we are given therefore feels banal.

Well written and often impressive as it is, demonstrating Langmead’s proficiency with prose and an ability to work with a plot and setting that in the hands of a less skilled writer would have given us a less striking result, Metronome makes for a quick and fairly enjoyable read, but not an exceptional one.

A free extract from Metronome (2017) is available here at Unsung Stories. Purchase on Amazon.

1 Harrison, “Very Afraid.” Uncle Zip’s Window. 2007. Archive.org.