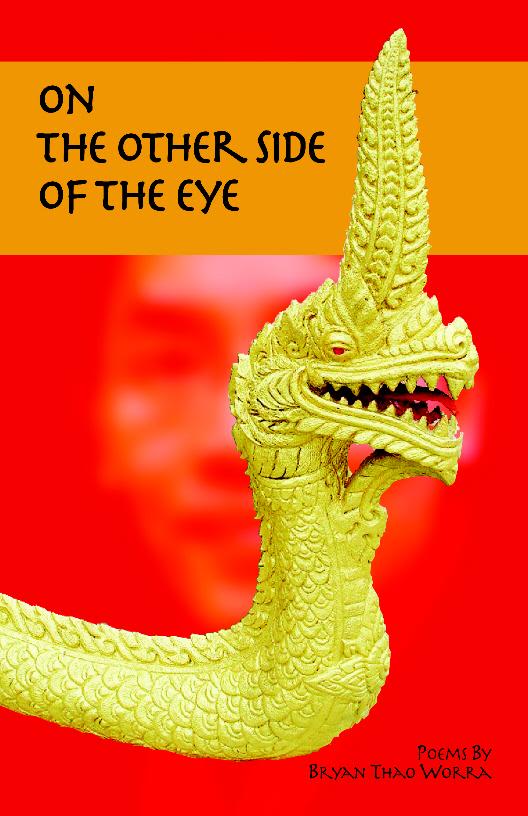

This summer, Lao American poet Bryan Thao Worra marked the 10th anniversary of his first full-length book of poetry, On The Other Side Of The Eye (Sam’s Dot Publishing, 2007). He holds over 20 awards for his writing and community service, organizing numerous literary and cultural events across the United States. His passion is to help refugees rebuild their literary and artistic traditions, particularly through the use of science fiction and fantasy. He is the president of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Poetry Association, an international organization founded in 1978. I caught up with him recently to discuss his extraordinary journey and where he’s going next.

This summer, Lao American poet Bryan Thao Worra marked the 10th anniversary of his first full-length book of poetry, On The Other Side Of The Eye (Sam’s Dot Publishing, 2007). He holds over 20 awards for his writing and community service, organizing numerous literary and cultural events across the United States. His passion is to help refugees rebuild their literary and artistic traditions, particularly through the use of science fiction and fantasy. He is the president of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Poetry Association, an international organization founded in 1978. I caught up with him recently to discuss his extraordinary journey and where he’s going next.

Congratulations on celebrating 10 years of On The Other Side Of The Eye. Can you tell us a little more about yourself? For example, how did you get started with an interest in literature?

Thanks, it feels like a great milestone for the book, and for our community as a whole. I’m a Lao American writer who came to the United States shortly before the end of the Lao Civil War in 1973 as the adopted child of an American pilot. I grew up in the American Midwest which was very different from Southeast Asia. The weather in that part of the US often meant staying inside, and I was fortunate to grow up in a home filled with books. I’d begun to show a talent for writing in grade school but really started getting my work out there once I began attending Otterbein University in the 1990s.

After that, there weren’t many years where I wasn’t writing. By 1999 I was getting published regularly and working with other refugees from Southeast Asia to share our stories and art with the world. I believed it was important for us to work together to rebuild our various literary and cultural traditions after the conflicts of the 20th century.

Have you always had an interest in science fiction and fantasy?

Growing up in the United States in the 1970s and 80s there weren’t many stories about Lao people. The closest we got were films like Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, Rambo and other works where we were always victims, enemies, or disposable objects of lust. In contrast, in science fiction, I could see more people who looked like me and had stories like mine. It was liberating to see those possibilities compared to what we saw in the mainstream media.

In a world like Blade Runner, it was supposed to be a dystopia, but it was still a world where you could have a Cambodian street geneticist or a noodle stand that served huge portions to their customers. In Star Trek, you had Asians who were regularly equal members of the crew, exploring the galaxy and helping others to solve their problems. You could watch a film like Big Trouble In Little China and see Asians both as heroes and villains in the story. I feel it was natural to get drawn to that. Which isn’t to say there haven’t been problematic stories in science fiction and fantasy, but at least here, we could see ourselves in the future in ways where we’re not an afterthought.

You’re involved heavily with science fiction poetry. Many of us hadn’t thought that was possible. Can you tell us more about it?

Strict “realism” in poetry is, in the grand scheme of things, a relatively new tradition. Looking at the traditions of the Ramayana, The Iliad, The Odyssey, The Canterbury Tales or the work of Edgar Allan Poe, William Blake, and so many others? Deeply imaginative verse has always been a vital part of a culture’s literary traditions. To thrive, a society needs to create work that considers the future, that finds a place for technology and the new inventions in our lives and how we relate to them and connect to them at a deep level.

Sometimes, science fiction poetry can be radical just for suggesting something like a Lao space program or imagining seemingly everyday ideas like a monorail system connecting nations we hadn’t previously thought would become connected. As we improve the capabilities of artificial intelligence, will they think along European and American logic processes, or take on a mindset closer to a Southeast Asian consciousness? How might a poem consider that? There are many possibilities.

I hope writers feel free to explore things at both a serious level and a more light-hearted level. What does a poem about a zombie apocalypse in Karachi look like? There are fascinating benefits for everyone when we feel free to push our imagination and language to the very limits of possibility.

What are some of the biggest lessons you learned from getting On The Other Side Of The Eye published?

You can’t be afraid to take risks and to write from a perspective that’s uniquely your own. That doesn’t mean be incomprehensibly outré, but you should be happy finding your own voice. To find ways to say something, even everyday things, in a way no one else might consider.

On The Other Side Of The Eye was the first full-length book of Lao American poetry that was looking at our journey as refugees through the lens of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. People weren’t expecting that, but it opened up tremendous possibilities for writers going forward from there. Lao were no longer limited to writing clichéd immigrant or refugee narratives, but had the freedom to write poems about anything their heart desired. It’s one of the things I’m proudest of about this book, even though, at the time, there were some very negative people in my life who said it was irresponsible to waste my time writing like this. History has since proven them quite wrong.

When you run into a point where you’re about to write about something no one else has written about before, that’s when you just take the plunge and try to write something, anything down, and see what happens.

You don’t have to worry about being the last word on the matter, but try to get a word in. Sometimes history will agree with how you expressed it, and your words will last the ages. Sometimes it won’t, but not for lack of trying. And that’s still a fine moment.

It’s important to get to a point where you’re comfortable with the idea that your first book will not be your last. Put together a book that ultimately you will personally enjoy reading, time and time again, even if no one else does. The very best of our books will be books that are capable of still surprising the author years later.

Who are some of the emerging Southeast Asian voices you’re keeping an eye on?

I’m presently keeping a particular eye on several Southeast Asian poets including Jenna Le, Sokunthary Svay, Krysada Phounsiri, Soul Vang, Cassandra Khaw, Burlee Vang, Mai Der Vang, Khaty Xiong, Pos Moua, Peuo Tuy, Bunkong Tuon, Mong Lan, Christing Sng, Kristina Ong Muslim, and Do Nguyen Mai, who’ve all been presenting some fine and imaginative work. I’ve also been following the prose work of Zen Cho, Aliette de Bodard, Joyce Chng, and Jaymee Goh. I think we’re going to see a golden age of Southeast Asian speculative thought in the next few years.

What would you recommend for editors and publishers who want to encourage more submissions from Southeast Asian writers?

I think it’s effective to build relationships with emerging writers and voices and to encourage them over a long stretch of time with a collaborative and supportive mindset. I hate seeing promising writers give up the pen because they were discouraged by seemingly harsh but well-intentioned critiques. Have conversations with them. Be open to their feedback and concerns, and understand that sometimes they will have a very long stretch between new pieces. If you’re really committed to Southeast Asian writers you’ll have to be constantly scouting and checking various lists and profiles every year for new and established voices. I’m hoping Mithila Review will continue to be an excellent literary space for writers in the region and around the globe.

What are you working on for your current literary projects?

My process is that I’m always working on several different books at a time as a writer. But I’m particularly taking a look at a manuscript that addresses a concept of the “apocalypse” and the end of the world when you come from a spiritual and intellectual tradition that believes in ideas such as karma and reincarnation. There are a few projects involving robotics, ghosts, and what it means to discuss many of the mythic heroes and monsters of our traditions in the United States.

Overall it ties into a discussion of what it means to nurture the imagination of refugees, which is often overlooked in the resettlement process. In the US we typically see refugee support efforts designed to focus on ‘practical’ skills at the expense of innovative thinking and problem solving skills. That’s a concern for me.

What are some of the things you hope to accomplish while you’re the president of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Poetry Association?

I recently wrapped up the first year with a number of good outcomes including an increased presence at science fiction, fantasy and comic conventions. I hope people see you don’t have to be an academic or a full-time writer to bring speculative poetry into your life as a reader or a creator.

We’ve been expanding readings across the US and doing more to encourage diversity in speculative poetry, especially from less traditional perspectives. We’ve been making stronger efforts to present the SFPA as an inclusive organization and a network we can turn to for constructive feedback, fellowship and support especially from an international perspective.

We’re about to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the SFPA in 2018, so I want our members to have a chance to look at what we’ve accomplished, but also to appreciate that there are many interesting ways for us to bring poetry to the world now: There are new technologies, presentation techniques, and changes that let us go far beyond the page and stage.

What are some of your personal rules for yourself when it comes to writing? When it comes to editing?

Personally, I think it’s important to focus on ideas over form, because I tend to consider an international audience. If your work relies too much on rules of form or rhyme schemes, when it comes time to translate it into Khmer, Japanese, German, French, Esperanto, or some other language, it’s often not going to cross over well. Interesting ideas matter!

There are some other key principles I try to apply. For example, I try not to write things I’ll be afraid to stand by ten or twenty years later. But I give myself space to be a young writer, one who will get better over time.

I don’t write using italicized words to denote a ‘foreign’ word or concept. In the US we don’t italicize sushi, tacos, ninja, vampire, aloha, Jedi or avatar. Why should Lao, for example, italicize sabaidee, kinnaly, or phi, then? I prefer not to write in a way that uses footnotes unless it’s likely to be obscure to everyone. One person’s Chao Anou is another’s JFK. Who are we to make assumptions, eh?

Even when writing the silliest of things, strive to confer wisdom, directly or indirectly.

What is one of your favorite pieces to recommend for readers who want to get an introduction to your writing?

My poetry goes in many different directions at any particular point, but some of the consistently popular poems readers get introduced to include “The Deep Ones,” “The Last War Poem,” and “On A Stairway In Luang Prabang.” I’d like to think that in all of my collections there is a good mix of pieces that are challenging, and pieces that are easier to understand, with the hope that my readers don’t give up, but make a good effort to try to solve the puzzling ones.

What words of advice do you have for aspiring writers?

Find your passion, don’t be afraid to carve out your own territory. In the process you have to be constantly looking for new ways to express familiar ideas and themes, and to ground them when possible within your own reality.

Make your landmarks, your streets yours and put them on the literary map in your own words, on your own terms.

A writer’s longevity rarely comes from writing about things agreeably, upholding the existing narratives, but from challenging those stories profoundly with a deep intent. You can’t be afraid of criticism, and you need to know when to stand by your principles and the best of your wildest ideas and dreams. You could change worlds.

And above all: Be patient with yourself, but get off your butt and write.