The sky above Mumbai harbour lit up.

Parzan Merchant, nine years old, craned his neck out of his bedroom window. He’d been practicing the song for the Independence Day celebrations at school tomorrow, which was why he was still out of bed so late at night. He’d heard the boom and rushed to see. As he watched, another fireball seared the horizon behind the close-packed buildings.

‘Parzan! Hey!’ His fourteen-year-old brother Kersi came in. Parzan’s bedroom was the highest in the old and crumbling house. It was suffocatingly hot in summer, drafty in winter, and right now in the monsoon it smelt of mould, but you could see the harbour from the window if you leaned out really hard. ‘Shove up,’ said Kersi, and jack-knifed his lanky body over the windowsill. Parzan sulkily gave way. ‘What do you think is happening, Kersi?’ he asked. ‘Is it terrorists, like in 2008?’ He’d been too small to see much of anything when the Taj Hotel had been attacked.

Kersi snorted. ‘Nah. That’s just your future going up in flames.’

‘What?’

‘Don’t you remember? That was INS Sindhurakshak. The submarine that exploded in Mumbai harbour in 2013. You sat up all night watching, little brother. Then you insisted I go out and buy the newspapers even though I said you could read them all on the net. You wanted to make a scrapbook, you moron.’ Water began to flood the room. ‘I told you it was a bad idea. The sea eats people.’

‘No!’ But the word wouldn’t come out. Instead of his bedroom window, Parzan’s thrashing hands touched the worn metal sides of the training tank in submarine school, buzzing with the absorbed terror of generations of first-time submariners. Kersi’s drowned face opened in a mindless grin. ‘You’re no hero, Parzan. You fed us all to your beloved ocean, didn’t you? Your whole family. You bastard.’ Fish nibbled at the ribbons of rotting flesh on Kersi’s cheeks. ‘You deserve this. You couldn’t even stop your crew from deserting. You loser. Loser! Loser!’

‘Kersi…’ The sounds bubbled in his throat. Kersi’s clawed hands reached for him. Parzan screamed.

He woke up. For a second he thought he really was drowning, then he realised it was just his hair. It was wet.

‘I’m sorry,’ said a female voice. ‘Your heart-rate was elevated and you were vocalising in your sleep. I deployed the sprinkler system to wake you.’

‘Uh,’ Parzan took a towel from the bar and wiped his neck. He was in the officers’ lounge of Arisudan, the state-of-the-art nuclear submarine of which he was commanding officer. Or had been. He wasn’t sure what he was now. A survivor, perhaps. ‘I was having a nightmare. People do, you know.’

‘I will tag the symptoms for future reference. I hope you are not too damp?’

He rubbed his head ruefully. ‘When did I fall asleep? I was reviewing the inventory, and…’ He fingered his left cheek. There was a dent in it from the edge of his tablet.

‘You stopped moving and your breathing slowed three minutes and forty six seconds ago.’

‘Damn. Wake me up if you see me doing it again. But don’t use the sprinklers. Just keep saying my name really loud.’ He thought a bit. ‘And don’t wake me when I’m in my bunk. Unless I ask you to. Or something happens. Do you understand?’

‘Yes sir. I have modified my protocols.’

He put the towel on the back of a chair to dry. ‘I suppose I should turn in. Monitor all wavelengths while I’m sleeping, Arisudan. Anything moves out there, I want to know.’

‘But sir, it is four hours till the end of watch. You cannot…’

Parzan’s patience snapped. ‘Damn right it is. Do you see anyone here who can relieve me? No? Oh that’s right, you in your infinite wisdom let the crew leave! So now I’m doing the work of 95 men all by myself. Pardon me if I don’t follow the rulebook on this.’

There was a pause. Then Arisudan said, ‘You are angry, sir. Have I disappointed you?’

Parzan held his head. ‘Why did you let them go?’

‘I believed that Executive Officer Carlton Caron was telling the truth when he said he was leading a sortie to bring back essential food and medicines. He said you had been temporarily unhinged by the tragedy of the Helios Fail. I saw that you were screaming and banging on the door of your cabin. Hence I concurred that your behaviour was unbefitting a commanding officer, and that I should—’

He nearly shouted, but stopped himself in time. ‘Look, I admit I was kicking the damn door, but that was because they’d locked me in! They didn’t want me to stop them from leaving. But it’s hell out there! All coastal cities have been obliterated. One third of the Indosphere’s landmass is under water. Our home port of Vishakhapatnam has been wiped off the face of the earth. Our VLF radio station at INS Kattabomman has been destroyed, so we can’t contact anyone without surfacing, which would mean our immediate destruction. So we’re stuck here on the bottom of the sea in the Singapore Straits, hiding from an enemy 35,790 kilometres above our heads!’

‘I am aware of the situation, sir. When XO Caron put me in survival mode before exiting the ship he updated my databases.’

‘Well then you know that a week ago, Delhi gave us orders to watch and wait. That was before Ramdhun’s space hotel opened fire on us, but I don’t care what anyone says, we don’t take orders from them. If Ramdhun has turned hostile, Delhi will deal with it.’

‘Yes sir. But Delhi has not communicated with us since then.’

‘I know! Look, I’m trying to do this right, okay? And I seem to be the only one.’ He got up and began pacing. ‘Whatever they may think, the men can’t help their families. I should know. I’ve known since 2032 when Mumbai sank into the sea. Once you become a climate refugee, there’s nothing left. Not even the ground under your feet…’

‘I am sorry, sir. What are your orders?’

He pushed his knuckles hard into his eyes for a moment. You can’t lose it now, Zany. Pull yourself together in front of the talking machine. ‘Take stock of the food we have left. Calculate how long it will last me. Our Supply Officer said we were down to three months’ emergency stock, but that was when we still had 95 people on board.’

‘Yes sir.’

‘And now I’m going to get some rack time. Wake me up if the world ends. Again.’

‘Understood, sir.’

Of course, once he was in his bunk, sleep deserted him.

—

The Helios Fail. Stupid name for the end of civilisation. All those doomsday movies about comets hitting the earth and nuclear wars. Hah. If the moviemakers were still alive, he reflected, they ought to be feeling ashamed of themselves.

Just over a week ago, Arisudan had surfaced off the Andaman and Nicobar islands after almost nine months of pre-launch sea trials, and Parzan had tried to raise Vishakhapatnam to give them the news of her excellent performance in every test and to request permission to return to base for refitting and handover. The last trial had involved diving to just above crush depth for her titanium hull, more than a kilometre below the surface. Arisudan had performed impeccably, but a sudden deep-ocean acoustic storm had led him to bring her up two days ahead of schedule. That had caused his first moment of disquiet: what kind of event could produce such a hurricane of sound so deep under the sea? The disquiet deepened into worry when he failed to raise Kattabomman, but Arisudan was in the Bay of Bengal where VLF reception was notoriously bad. Once on the surface, his communications officer tried every band and channel, even the civilian ones, and got nothing but static. Vishakhapatnam would not respond.

He’d been about to head home on high alert when Delhi contacted them. ‘This is the Vice Chief of Naval Staff of the Indosphere. INS Arisudan, what’s your status?’

‘We can’t raise any military asset, sir. Or civilian, for that matter. Are we in a state of conflict, sir? And if so, with whom?’

‘We are not at war, commander, if that’s what you’re asking. You know war has been off the table since the Ramdhun New Deal of 2024. The Indosphere is now a region of peace and cooperation. No, Commander, the aggressor here is the planet itself. We have lost major military assets due to yet another climate fail precipitated by human error. This is far worse that Singapore in 2023 or Mumbai in 2032. Ramdhun Corporation is assisting us in assessing the damage. We believe the continent of Antarctica has been de-iced.’

‘De-iced, sir?’

‘Yes. Before you embarked on mission, you will recall that the Helios energy major of New York had applied for permission to drill for oil in Antarctica as an eighteenth birthday present for the Ramdhun One Thousand. Six weeks ago permission was granted.’

Parzan looked at his XO. Carlton frowned. The Admiral went on, ‘Yesterday, 23 December 2048, was the Helios Inauguration and initial drilling run. At about 1100 hours IST, the Helios drill rig broke into an active volcanic vein under the southern polar continent. The explosion seems to have de-iced the entire landmass and collapsed the Ross Ice Shelf. Coastlines worldwide have been hit by multiple supersonic tsunamis. Satellite imagery, as far as we can tell through the planet-wide haze caused by the Helios Fail, shows loss of coastal Andhra, Orissa and all of Bengal. The Ganga valley is submerged up to Varanasi. The west coast is less damaged but no facilities have survived, not even Ezhimala. There is no command chain east of Allahabad. Eastern Command is gone.’

‘I see, sir.’ Parzan was acutely aware that most of the seven officers around him had homes in the places the Admiral had named. ‘Sir, our rations are low. We were scheduled to make port and begin mission debriefing in a week’s time. Is there any alternative port we could head for in the interim?’

‘Negative, Commander. Stand off to sea and await instructions. What is the status of your emergency supplies? How long can you last on short rations?’

‘Sir, I will need to make an exact estimate but I believe with good management, we could last another couple of months without restocking. Three at the most. As you know, sir, Arisudan was in sea trials and we were to hand over to the A crew for formal launch. She performed well on all tests and our systems are optimal. Our ICBMs lack warheads, so we have no long-range attack capabilities. However we are carrying our full arsenal of live torpedoes, decoys and mines. The reactor is stable and can power us for several decades if necessary. The shortage of rations is the immediate problem.’

‘Noted. We’re aware that Arisudan is not fully combat-ready, We don’t expect that you’ll be required to engage, but we can’t rule out opportunistic attacks from hostile powers seeking to capture markets in the aftermath of the Helios Fail, so remain at yellow alert. Your objective is to keep your boat safe while we assess the situation. Passive sonar only, and radio silence.’

‘Understood, sir.’ Parzan signed off and turned to his officers. ‘Pilot, take us down to 100 metres.’ The pilot and copilot began their dive prep, which on Arisudan was much simpler than the protocol they’d used on the diesel electric subs Parzan had trained on, back in the 2030s. ‘Ops, trail a wire and listen to all radio channels. Sonar, trace all contacts including neutrals and friendlies. Engineering, check on propulsion, oxygen and water. Supply, take stock of all consumables including medical and give me a full report. Tell the crew that everyone’s on short rations as of now. Nav, did we get a GPS fix?’

‘Satellites are still operational, sir. We’re four hundred kilometres west-northwest of Indira Point.’

‘Okay, hold position for now. XO,’ he turned to Carlton, ‘scramble the men, including off-watch. I’m going to address them all in the Missile Compartment in twenty minutes.’

‘On it,’ said Carlton, then hesitated. ‘I can get them there in fifteen, if you like, Zany.’

Parzan shook his head. ‘I appreciate it, CanCan, but I need twenty minutes to work out what the hell I’m going to say to them.’ They looked at each other grimly. ‘Alert the crew and prepare to dive.’

—

Parzan squeezed his eyes shut as he lay on his bunk. He was exhausted, but his whole body was twanging with tension. Stand down, he told himself sternly. He felt a twinge of residual guilt at not finishing the watch: it was just the habits of a lifetime protesting the breakdown of all sanity. He told himself to rest: he was now the only soul on whom Arisudan depended, and he had to keep functioning for her sake. He tried to push his thoughts away, but his mind insisted on turning over like an idling engine. Once again it slipped a gear and dragged him down the rubbish-littered slope of his memories.

Grandma Freny could always be relied upon to listen. She was the only one in the Merchant family who didn’t snort or sneer when he said he wanted to join the navy. She had helped him make the scrapbook back in 2013, and she didn’t agree when his mother said it was a morbid thing to do. ‘He’s going to have to grow up in this world,’ Grandma Freny had told her daughter-in-law grimly. ‘He’s old enough to start learning about it now.’

‘You shouldn’t encourage him in this navy nonsense. It’s too dangerous. Why don’t you tell him to think about helping Kersi when he grows up? The stud farm is too big for one boy to manage.’

‘It’s his life.’

Parzan went on sticking stuff in his scrapbook and pretended he couldn’t hear them talking above his head. But after his mother had gone, he asked Grandma Freny, ‘Is the navy really dangerous?’

‘Everything’s dangerous. Horses kick, ships sink, plans go haywire.’ She grinned toothlessly. ‘Doesn’t mean we stop living.’

‘Is it hard to become a sailor?’

‘We’ll have to find out, won’t we? But I’m pretty sure the first step is studying hard and doing well in your exams, Akoori.’

‘Grandma, don’t call me Akoori! I’m not a baby any more.’

She chuckled. ‘You still like my scrambled eggs, don’t you, like you did when you were four? So I can call you Scrambled Eggs till you’re as old as I am.’

He couldn’t argue with such infuriating logic.

In November 2023 Kersi married Havovi, a sweet chubby girl of whom his mother thoroughly approved. Parzan was happy for his brother, but the wedding wasn’t really fun because his school final examinations were coming up in two months’ time, and every relative either asked him how he was studying or which colleges he planned to apply for. To his great relief he managed to dodge any serious grilling, then Kersi went off on his honeymoon to Singapore. The young couple had actually wanted to spend their honeymoon on the floating private city of New Singapore, a modern engineering marvel built by Ramdhun Corporation out in the Straits, but it wasn’t going to be opened to the public till the grand inauguration on 4 January 2024. Only shareholders and VIPs were currently allowed to dock there. But their cruise ship did pass the city, and Havovi excitedly posted the photos of the two of them standing before the graceful spires and bridges of New Singapore as it floated past. Parzan’s father came to show him the pictures on Sharebox.

‘You should think about a career at Ramdhun, if you like ships so much,’ his father told him. ‘Do your B.Com and apply. They’re the largest single corporate house in Asia, and they’re run by an Indian family, the Vaghelas. They’ve had a presence in India since 2020, when they stepped in to build corona hospitals and quelled all those riots and protests and whatnot. They practically run the country now. What do you say, Parzan?’

‘I’ll think about it, Dad.’

Kersi returned a week before Christmas, laden with Ramdhun-made presents for the whole family. Parzan got a VR-ready Ramfone, but his father locked it up in his study and said, ‘You’ll get it if you do well and get into a good college.’

‘Oh, let the boy enjoy himself till Christmas,’ scolded Grandma Freny. ‘Parzan and I always go carol-singing with Sharon and Chaim; they’ll be so disappointed if he doesn’t come this year. He’ll study better after that, won’t you, Akoori? Come on, dinner’s ready.’

‘No!’ Havovi’s voice rose in a near scream. ‘We were just there! How can this be happening? Oh God!’

‘What’s wrong?’ Father asked as they all rushed into the living room. The two women were staring at the television. ‘It’s Singapore,’ Mother said grimly. ‘It’s gone.’

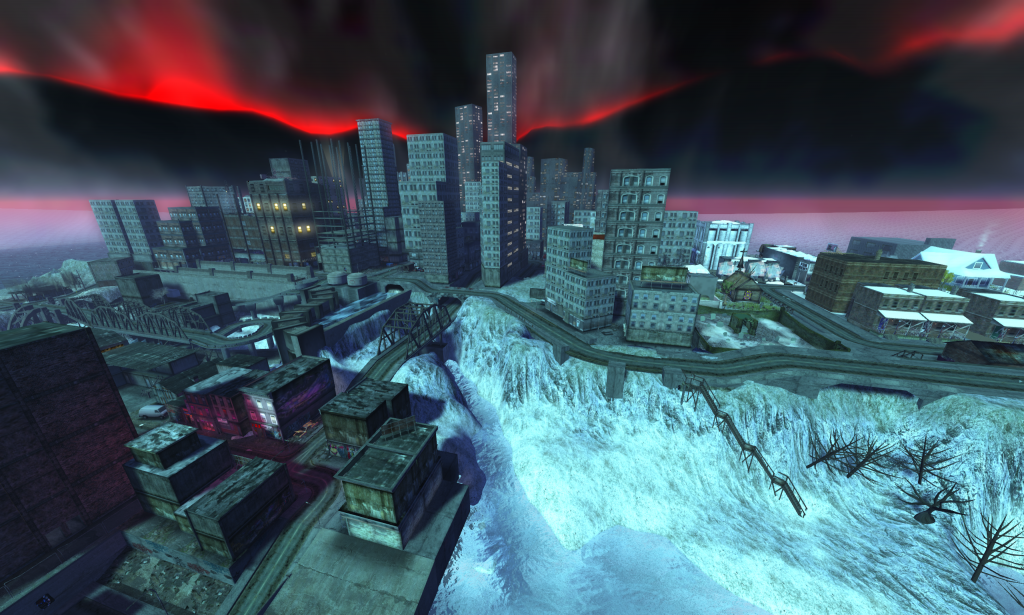

‘Gone? What do you…’ But Father was staring at the television too. The studio feed cut to the holiday lights of the great city, decorated for Christmas and the New Year. ‘This evening, a day before Christmas Eve with Singapore’s shopping season at its height, disaster struck when…’ As they watched, a strange darkness rose behind the slender skyscrapers, and down that darkness ran an eerie waterfall of light, forming for a moment the hazy outlines of… what? The commentator said, ‘Just before 9pm local time, a series of megaquakes disturbed the seabed south of Singapore, causing an enormous tidal wave laden with mud and rock to wash over the entirety of Singapore Island, burying the city and all but a handful of its inhabitants. This is a tragedy that no one thought would ever happen. Just seconds before the wave hit, the lights of the city were reflected on the underside of the giant curl of water, hundreds of metres high, creating this optical illusion of a winged figure poised to swoop down upon the city. People are calling it the Angel of Doom.’

The rest of his memory of that evening was just flashes. The faces of climate refugees, wiped blank by shock. The helicopters and private jets of the super rich, who had left Singapore harbour just minutes before tragedy struck and turned up for a ‘pre-launch party’ at New Singapore. The aerial view of the floating city with a high wall of expensive yachts and cruise ships moored around it. The smoke canisters that went off just as the climate refugees in their tiny boats arrived at New Singapore. The thick pall of smoke hiding the floating megalopolis. Then the smoke clearing, a few minutes later, to reveal nothing outside the circle of cruiseliners but the empty restless sea: no boats, no refugees, not even wreckage. The breezy dismissals of Ramdhun top management, who claimed to know nothing about the people or their fate.

At first Havovi cried and wailed, then as the replies of Ramdhun worthies became more and more flippant, she grew tightlipped and red-eyed. Grandma Freny tried to console her, and Parzan simply watched with his heart in his mouth. Much later it occurred to him that of all of his family, only Kersi had sat with his back to the television most of the time, playing a wargame on his phone.

—

‘Commander Merchant? Are you awake? It’s been eight hours.’

‘Already?’ He sat up. ‘Feels like I just lay down. Any news?’

‘No contacts, Commander Merchant. I have calculated our food reserves. Irradiated items in deep storage such as rice, wheat, pulses and powdered milk will last up to three years or longer, sir. Fresh foods will not last nearly so long. Some will have to be cooked and frozen. I regret to inform you, sir, that you will have to boil or fry 127 eggs. Once that is done, 189 boxes of assorted foodstuffs will have to be manually transferred to deep storage.’

He grunted a laugh. ‘Okay, this will give me something worthwhile to do.’

‘Sir, in my database I have over two hundred egg-related recipes. Would you like me to…’

‘Don’t bother, I know what I want to do with them.’ He got up and pulled on his shorts. ‘Grandma Freny didn’t call me Akoori for nothing.’

It felt strange to be walking alone down Arisudan’s softly shining corridors. He’d spent most of his working life in incredibly close confines, honing the submariner’s particular ability to maintain personal space when everyone was practically living in each other’s laps. The old subs he’d trained on had been full of pipes and conduits and weird protuberances that poked themselves into your gut if you weren’t careful, as if the human crew were interlopers in their kingdom. By contrast, Arisudan was all novel self-cleaning materials in smooth ergonomic curves. The RamTech engineers who’d built her had honed their skills designing the interiors of Indraprastha, the Ramdhun space hotel, and they’d used many of the same design concepts in Arisudan. When their trial voyage had begun, the crew had taken weeks to tire of the Star Trek jokes.

Arisudan’s skin was a nanorubber-coated titanium shell, inside which the fixed structure was two matching hulls like the buns around a hotdog. These contained the living quarters, command infrastructure and crew spaces. The space in between the halves was for the ‘hotdog’ (basically the Missile Compartment, Supply and Storage) to be slotted in. These sections could be lifted out by cranes in drydock, allowing the gigantic 110-metre long warmachine to be restocked in a matter of days if need be. A huge change from the way subs had been loaded twenty years ago, with the crew forming human chains and passing stuff from hand to hand. When he’d first seen Arisudan’s specs in 2047 he’d been a little nervous about the idea of a sub with detachable sections, but when the lockout trunks were nanosealed into place you couldn’t tell where the fixed hull ended and the trunks began.

Supply was amidships, close to the reactor because the heat exchangers in the cold storage used a lot of power. He passed the dining hall and headed through the swing doors to the galley. All was neat and in order; he felt a moment of pure, hopeless, gut-wrenching love for his crew who, in the middle of the world’s ending, had stowed their tools, fastened their locker doors and left everything shipshape for the next shift. He bowed his head and shut his eyes.

—

He’d failed the entrance test. In 2024 the National Defense Academy rejected him, as did the Naval Academy. Shaken, he’d joined a local college to study commerce. Kersi started giving him book-keeping work to do for the stud farm. The business was not prospering: its glory days were long over. The rich men who had kept it alive were all dying of old age, and the younger generation of richies didn’t care. Cars were their thing, not horses. Kersi was trying to sell the farm to Ramdhun Corporation. Rik Nehra, Ramdhun’s Head of Image Management, came to see it in June 2024, just after the Ramdhun New Deal was signed. In spite of the large quantities of their father’s scotch he drank, Nehra said there was very little prospect of a deal. Grandma Freny refused to meet Nehra, saying he was the glib PR man who had explained away the vanishing of the refugees in 2023. She and Parzan sat in the kitchen until he left.

Grandma Freny shrugged when Parzan told her he’d washed out of NDA admissions. ‘Try again,’ she said firmly. ‘No one ever made a perfect dhansak the first time they picked up a spatula. Don’t listen to your moron brother: try again.’

‘Kersi’s smarter than me, Grandma.’

‘Kersi’s good at figuring out what other people think is smart. But you know, Parzan, really smart people don’t need to do that.’

So he studied commerce by day and prepared for a second shot at the entrance exam by night. Grandma Freny’s faith proved correct, because he got into NDA in the July intake, although direct entrance to the navy still eluded him. Still, at least he was on his way to joining the armed forces. He’d have to opt for a lateral transfer to the naval academy in his senior year, if he did well enough. He was pretty sure the regular army was no fit place for him.

Kersi was furious at the prospect of having to handle the family’s slow slide into bankruptcy all by himself, and even tried to get his father to forbid Parzan from going. ‘It’s my life, Dad,’ Parzan tried to smile when his father came to grill him about his life choices. A hollow feeling budded open in his heart.

‘No,’ said his father. ‘It’s not your life. Do you know why you were named Parzan?’

‘I know. Grandma Freny told me the story. Your young cousin went missing in Ahmedabad during the riots of 2002. I was named for him when I was born two years later.’

‘And now you want to go to sea. What if you go missing too? How much more must this family take?’

‘I’ll be safe, Father.’

‘Like Sindhurakshak?’

‘That happened eleven years ago. The engineering of subs has improved vastly since then. Dad, I have to do this. I can’t live with myself if I don’t.’

His father said nothing. He didn’t trust machines.

Parzan took the new Ramdhun-built bullet train to Pune. Everyone on the train was talking about the Ramdhun New Deal, which the government had signed just days ago and which was now in force across the Indosphere. The pandemic and the riots, oppressions, midnight arrests and mass movements of 2020-21 had left the economy on the brink of collapse and shredded people’s confidence in the government. As the protests were crushed one by one, TV analysts wailed about the loss of productivity that followed in their wake. The government’s ruthless suppression of the people didn’t quite manage to distract the nation from the catastrophic collapse of the economy. By 2022, as the world opened back up after the pandemic, unemployment hit a record high, the worst since Independence, even as markets were booming in the wake of the rise in online work. Then Singapore was washed away and the world had plunged back into recession, losing what little hope had dawned after the pandemic. In April 2024 the business houses of the Indosphere had appealed to Ramdhun to clean it all up and get the economy running again.

Central elections were already overdue, but the news channels only showed endless footage of every Indian city thronged with service-people in smart Ramdhun uniforms, building and painting and cleaning and modernising. No one knew exactly what the terms of the Ramdhun New Deal were, but it was rumoured that all domestic government ‘services’ were now in the hands of Ramdhun, while the government would restrict itself to foreign relations and defence spending. Amendments were passed to drastically reduce the power of the regional governments, since the analysts of the Centre for Proactive Policymaking at Jai Narendra University put out terabytes of data to show how these governments had abetted the riots and turmoil. Rik Nehra publicly said the states were the biggest obstacles to restarting the economy.

Selvam Vaghela, CEO of Ramdhun, visited the Prime Minister and had a ‘very positive meeting’. Vaghela was impeccably dressed in designer ethnicwear, although he did not speak any Indian language. ‘Signs of hope!’ squawked the talking heads. ‘The days of anarchy and mismanagement are over!’ His face was everywhere these days. As Parzan got off at Pune station and headed for the taxi stand, Selvam Vaghela’s voice boomed from a giant screen above the exit. ‘The last few years have proved that the old ways are wasteful of human potential. Ramdhun wants the Indosphere to be a zone of opportunity, security, peace and prosperity. Women and minorities should be free to work…’ Parzan got in the cab and Vaghela’s voice faded in the wind.

For the next three years, Parzan did his best to keep his mind on his training and ignore the increasing weirdness of the world around him. He made few friends at Khadakvasla. He was acutely aware that if he didn’t get into the Naval Academy he’d have broken his father’s heart and alienated his brother for a future he didn’t want. But when the time came, his luck held: his name was on the list of qualifiers for Ezhimala. He was finally going to be a sailor.

Home leave that year was hard. Havovi’d had a daughter, Minoo, in 2025: now she complained that Kersi was pestering her for a son. Parzan’s elder brother had already named the child Rusi and was fitting out Parzan’s old room as a nursery. Kersi seemed curiously confident that his next child would be a male. Parzan thought it was because of the Ladbubble, the sudden mysterious spurt in the birthrate of boys that the press kept talking about: nowadays two boys were being born for every girl, apparently. Meanwhile Ramdhun Wellness had made the Merchants an offer to convert the stud farm into a vaccine factory and build a new Ramdhun township on the extensive pasturage. Kersi and their father had screaming fights every night. Kersi was ready to sell on any terms, but their father was shocked at the prospect of turning his beloved horses into pharmaceutical battery hens. Parzan had no help to offer any of them, so with Grandma Freny’s blessing he’d gone south as soon as he could decently get away.

The Naval Academy was spread over acres of beautiful Kerala backwaters. The sea revived his spirits after the claustrophobia of home. He hoped he’d fit in: the others in his batch would have joined as freshers and he knew he’d have to learn the culture all over again. First day at breakfast, he overheard voices from the next table. They were talking about the Ramdhun New Deal. Someone said ‘good riddance to all that democracy bullshit’ and other voices murmured agreement. He was only half-listening: by now the constant bickering between his brother and father had created protective rough spots in his brain, but he frowned as another voice joined the conversation. This voice was different: clear, low and precise. ‘Democracy was invented on the water,’ it said. ‘Arguably the first modern democracies were pirate ships. Even military vessels are more democratic than army platoons. They have to be.’

‘Oh shut up with your ancient history, CanCan. We don’t want to hear all that stuff about the boogie woogies any more.’

‘Huguenots,’ said the voice. ‘Then don’t talk about democracy in front of me.’

‘You should go teach in some college. Navy men don’t think. They act!’

‘Incorrect,’ said CanCan. Parzan was listening with full attention now. ‘If you’re a sailor, you make one mistake in a highly technical task and that’s it, you’re all fish feed. You can’t afford stupidity on a ship.’

‘Huh. What do you know about it, you ding?’

‘Nothing, really. But my family’s been on the ocean since 1619, one way or another.’

Parzan turned to watch the speaker. He had a shock of brown hair, a serious square face and a lanky body that had not a spare inch of flesh on it. Right now his eyes were hard as pebbles. ‘And by the way, I’d prefer it if you called me firangi rather than dingo. I am not Anglo Indian: I don’t have a drop of English blood in me. I’m Franco-Bengali. Firangi is an acceptable alternative.’

The other cadets at the table looked at each other, totally out of their depth, then bent their heads to their idlis and dosas. They all sidled as far away as they could from the soi-disant firangi. Parzan picked up his plate and came over. ‘Mind if I join you? I have some questions about pirates.’ He extended a hand. ‘Parzan Merchant. I don’t know why, because I’m really boring, but they call me Zany.’

The hand was shaken. ‘Carlton Caron. And for reasons you’ve no doubt deduced, they call me CanCan.’

Parzan thought about that. ‘Scandalous, spectacular, difficult and French?’

Carlton raised his glass of pineapple juice. ‘Salut!’

—

He’d forgotten how healing it was to chop garlic and tomatoes and onions, select spices, heat oil, wait for the chuckling that said it was time to begin. He’d learned to cook in 2032; Grandma Freny had taught him. But that was after everything had gone wrong. He stirred the onions to brown them evenly, then added the tomatoes and chopped peppers. Finally the eggs went in, a whole dozen of them beaten in a jug, then all he had to do was wait for them to firm up and stop his tears from falling in the pan.

That final year at Ezhimala had been heaven. For the first time in his life he’d started to feel like an adult, someone in charge of his own future. His mind was also being challenged in ways he’d never faced before, and part of the challenge was keeping up with Carlton. Carlton was focused with serene certainty on the process of making it into the submarine training school at Vishakhapatnam, and his poise started to nourish Parzan’s own rather battered self-confidence. Zany was soon spending nearly every free evening listening to CanCan’s stories about the sea. ‘Don’t expect the other guys to like us,’ CanCan said. ‘Submariners have always been the most hated of all the naval personnel. By their own surface-sailing comrades and by the enemy.’

‘Why?’

‘Because for many years it was not thought honorable to descend into the depths and strike from hiding like a thief or a brigand.’ Carlton pinched his hydrodynamics textbook shut and tossed his tablet aside. ‘A ship is helpless against a sub. Once the world had submarines, there were only two kinds of vessels in the ocean.’

‘Subs and targets?’

‘Correct. That’s why during World War I they actually called us undersea sailors “pirates”,’ CanCan chuckled. ‘We retaliated by painting the Jolly Roger on our hulls. Along with symbols of our kills. Some crews still do today.’

‘Could be seen to be in poor taste.’

‘Not if the other side started it. They wouldn’t even let us call our vessels “ships”. The word for a sub is still “boat”, even today, but now we use the word with pride.’ CanCan leaned back and put his feet up on his desk. ‘There are two ways of looking at war, Zany. One way, the way you probably recognise: war is a ritual, a necessary dance whereby men and nations and other big bods decide who is the mostest, and therefore it must be done right, with the appropriate posturing, rules and lingo.’

‘I take it you don’t approve. What’s the second way?’

CanCan’s look became grimmer. ‘War is what you do to survive, to stop the injuries and the damage and the bullying, and therefore it must be done right, as cheaply and painlessly and quickly and effectively as possible. That’s where subs come in. American subs won the Pacific war in 1945, not the goddamn atom bomb. They destroyed Japan’s merchant shipping and starved the country of oil and food. It’s the only way to take down an island nation that will not stop.’

‘So you’re saying that subs are effective because they’re kind of… cheating?’

‘All victory is cheating. And rewriting the rules. Don’t kid yourself that war is honourable. That’s just something they tell us to make us do our jobs. War is hell.’

Parzan frowned. ‘If you think that, then why do you want to be a submariner?’

‘Because someone has to.’ Carlton waved a hand. ‘Subs end wars because they’re nearly unstoppable, they can be anywhere, carrying ten ICBMs, each of which can wipe out a whole province. Nuclear submarines can stay at depth for months, even years if they have to. Just the knowledge that they’re in the ocean keeps all the crazies shut up in their boxes. I hate war, Zany, so I’m obliged to do what I can to make sure the world sees as little of it as possible.’

‘So it’s like being a sanitation engineer?’ Parzan meant it as a joke, but Carlton nodded seriously. ‘That’s right. If you do your job correctly, no one even knows you’re there.’

—

When Parzan faced the enlisted men in the Missile Compartment shortly after the Admiral’s radio message, he still had no idea what to say to them. The fifteen officers stood facing the men in their ten neat ranks of eight, flanked by the giant brown vertical cylinders of the missile tubes in two deadly colonnades. The crew called this area Vrindavan, because you could pretend it was a forest and go for a jog around it. Parzan wondered if he should tell them everything, given that there was nothing the men could do to help their families now. Submarine protocol dictated that you didn’t give people bad news until their tour of duty was over. But on the other hand, this wasn’t just a death in the family. This was the end of the world. ‘Men, I’ve called you here to tell you we will not be making it back to our home port of Vishakhapatnam. Instead, we will remain at radio depth and monitor all channels. There is currently no way to reprovision, so as of now we are all on short rations, officers included. I know we’ve been at sea for nearly nine months now and you’re all anxious to return home. As soon as we get more news from Delhi, I’ll be able to tell you more. Hopefully 2049 will see us home. Dismissed.’

No one moved. He frowned slightly. ‘Is there a problem?’

‘Sir,’ said Leading Seaman Shivsundar Nanda, ‘Is it true that Orissa and Bengal are gone?’

Instantly a hubbub arose: Andhra? Kerala? Tamil Nadu? The Konkan coast? Nanda’s voice cut through the noise like a knife. ‘Are we at war, sir?’

Parzan shook his head. ‘No, as far as I know, the Admiral said this was not caused by a hostile act but a climate fail, though probably there was some human agency…’

‘Is it true we have no homes? What happened to our families? Sir?’ asked Signals Officer Benu Chaudhury. His face was grey. ‘We’re the warriors, not them, we’re the ones who should be…’

On any boat, rumours are rats. No point wondering who had spilled the beans. Parzan waited for the noise to die down. ‘We don’t know anything yet for certain. Our orders are to await instructions. It’s up to the land-based forces to deal with any emergency. We have to figure out how to survive in the meantime.’ He looked at the rows of anxious faces. None of them were over thirty five, and most were much younger. None had seen active combat; there hadn’t been any naval engagement since the Chinese standoff of 2025, and half of them hadn’t even been born then. He knew the names of their wives and children, he’d seen their faces in pictures, shadowed by the trees of home, and now he could feel flashes of the pain they were all feeling. It was familiar: sixteen years ago he too had been through this hell.

The noise died down. Their training was reasserting itself. He said, ‘Be advised that there is nothing we can do to help the search-and-rescue people. Delhi has promised to notify us the moment there is concrete intelligence. Right now all we know is that Antarctica has been destroyed.’

‘Antarctica?’ Benu Choudhury was staring at him. ‘How could that happen, sir?’

‘The Helios Corporation!’ exclaimed Petty Officer Joyraj Mahato. ‘They applied for a lifting on the ban on oil drilling in Antarctica. But there was no way they’d ever be given permission!’

Once again the hubbub rose. ‘So we’re climate refugees? Climies? The rest of the country won’t take us in. They never do!’

‘Ten-hut!’ Carlton shouted, and they stilled again at the reminder, but their eyes flashed and their faces worked. CanCan said out of the corner of his mouth, ‘You have to level with them, Zany.’

Parzan opened his mouth to reply, but the deck bucked violently under their feet. Alarms went off all over the ship. Parzan grabbed a radio mic. ‘Ops!’ he bellowed. ‘What was that?’

‘Ordnance. Taking evasive action, sir.’

‘Deploy countermeasures and dive to 500 metres! I’m on my way.’ The deck bucked again. ‘To your posts!’ he yelled to the men, who were already scrambling. He ran with his officers at his heels all the way to Control. ‘Who’s shooting at us?’

‘Indraprastha. The Ramdhun space hotel,’ said the officer on duty. ‘They’re launching smart missiles from orbit. We managed to fool the first two with decoys, but they’re still spinning them up.’

‘How did they find us? And what the hell do they think they’re doing?’

Ops was pulling up displays and looking worried. ‘The AI is analysing the trajectories of the shots. It thinks they’re tracking our thermal wake.’

A third shockwave threw them all at the far bulkhead. ‘That was too damn close!’ Parzan shouted. ‘Make for the Sunda Straits. We need islands to scatter our wake.’

‘Zany, the sea’s too shallow for us to dive worth a damn in the Straits. If they come after us we’ll be as helpless as a baby in a bathtub.’

‘Diving won’t help if they’re tracking us: the missiles will just push us down to crush depth. We have to stop them getting a lock on us. The noisier our position, the better chance we have of hiding. And have the AI put us in stealth mode. We need to be a hole in the water.’

Dropping decoys after her, Arisudan crept in among the islands like a clownfish into corals.

—

Parzan stirred the tenth and last batch of scrambled eggs to cool it. The euphoria of his passing-out parade at Ezhimala had evaporated in minutes when he came home in May of 2030. Carlton had been called to submarine school almost before he finished at Ezhimala. ‘Have patience,’ he texted Parzan. ‘You’ll get in too.’ Parzan had his doubts, but he just sent a smiley face and took the train home. He arrived just as Havovi went into labour with little Rusi. The baby was born in the early hours of the morning, but immediately they knew something was wrong. Rusi would not stop crying. If he was held, he screamed as though red hot pincers were biting his flesh. He refused to take his mother’s breast, let alone suck.

Five days after birth, he died. The whole family broke down in grief. Their crying was echoed by the house down the lane, then the one across the park. Suddenly, all over the world, boy babies were dying of some mysterious disease that gave them agonising pain. Women’s anger spilled out, emptying the kitchens and schools and playgrounds. Kersi confessed to Parzan that he’d taken Humane Choice, the rather shady vaccine made and sold by Dr Pradip Shankar, medical genius and main man of Ramdhun Wellness. Humane Choice ensured that men would have mostly sons, but Shankar had never quite explained how it worked, or what the risks were. Of course, the good doctor denied any link between Humane Choice and this new disease. ‘Don’t tell Havovi,’ Kersi pleaded, and with a heavy heart Parzan promised to keep the secret.

The press called 2030 the Year of Fear. It felt like a return to the bad old days of 2020 when every city had been at war with itself, and contagion had stalked the world. But this was different. As mothers rioted on the streets or dissolved in tears at home, commentators explained how this new scourge would not harm the GDP and might even be a positive factor for demographic change. ‘It’s the Ladbubble collapsing,’ said Rik Nehra, when he was asked if he was worried. ‘In any case, we have years to figure this out before it becomes a real problem.’ Hospitals were choked with newborn boys who wailed like creatures caught in traps until they fell silent forever. The doctors knew only that the babies were being born with hypersensitive skins and hyperactive immune systems: if starvation did not kill them, anaphylaxis did, and they proved to be allergic to nearly everything. Mothers marched for their sons’ lives, and when that didn’t work they burned cars and broke windows. Kitchens across the globe were cold, schools empty, husbands went without meals and laundry, offices and factories were in chaos. Men’s rights groups called for a crackdown on ‘the bitches’, while spiky graffiti appeared on public walls, spelling out the words ‘Bitch Wars’. Dr Shankar went public to say the cause of these neonatal deaths was a ‘hostile prenatal environment’ but refused to release any data to support his claim.

In the middle of his family’s grief, Parzan got his call letter from submarine school. Grandma Freny insisted that he go. He’d have to be away for six months’ training on shore, and then another six months on an actual sub: a whole year of isolation. He felt guiltily thankful. As he gritted his teeth through the weeks of tests and training, he got intermittent news from home. Grandma Freny told him Dr Shankar had announced that he would find a cure for this new scourge, which the good doctor had christened Male Hypertoxic Syndrome. She didn’t think Shankar could save the babies. ‘He’s originally from Chandigarh,’ she said. ‘He left because people started asking questions about his precious vaccine. And then these Vaghelas threw their money at him. Bunch of crooks and thieves.’

But Ramdhun announced that one thousand of the world’s wealthiest newborn boys had signed up for the Shankar Cure, along with their powerful parents who would be co-sponsors of the research. The babies, quickly nicknamed the Ramdhun One Thousand or R1K by the press, were collectively the heirs to the richest corporate empires on the planet. Shankar declared that saving these babies would safeguard the economies of the world, bring back stability to the markets and protect millions of jobs and livelihoods. Then, once the technology had been developed and the R1K were safe in the arms of their one-percenter parents, he would upscale the cure for the general public. So the world settled down to await the outcome of Shankar’s experiment, although it would come too late for little Rusi and the boys of his generation.

The Shankar Cure was top secret: even the mothers weren’t allowed to see their babies in Shankar’s high-security facility on New Singapore. Their milk was pumped out by machines, triple filtered and fed to the babies remotely. After one year the thousand babies were all still alive, and the mothers were sent home. Ramdhun released carefully edited videos of the boys in their clean glass bubbles: they seemed normal. The wait for the boys’ return stretched on. Parzan finished his submarine training to find that Havovi had fallen in on herself like a sandcastle undermined by the tide. Grandma Freny was doing her best to look after Minoo, now six. The little girl would buzz around her like a bee seeking honey. Grandma Freny would say, ‘Minoo, what will you be?’ And Minoo would put a pot on her head and say ‘Minoo Merchant, space explorer!’ Then Grandma Freny would put a pot on her own head and say ‘Freny Merchant, space explorer!’ and they’d make whooshing noises as they took off. Parzan’s heart ached for them both.

He tried to make life easier for them. The kitchen was filthy: he took all the jars down and cleaned them till they sparkled. Grandma Freny told him to put them all back exactly as he’d found them, and he thought he’d done so. But that night Kersi took one taste of the titori and spat it across the room. ‘What’s wrong?’ Parzan cried. But then he too took a taste and turned pale. ‘Oh no!’ He ran to the kitchen. The salt and sugar jars were identical but for the words SALT and SUGAR on them, and he’d inadvertently switched their places. ‘But Grandma Freny, didn’t you notice?’ Grandma Freny gave a half-smile. ‘I have cataracts, Akoori.’

‘Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘You were at sea, and I hadn’t the heart.’ Parzan took her to an ophthalmologist that very day. But it turned out she also had the beginnings of glaucoma, and the doctor recommended that she be taken to Vellore for treatment, or if they could afford it, New Singapore. Parzan booked them both on the next flight to Vellore. ‘Good thing I cleaned the kitchen or you’d never have let me know. Why must you be a saint?’

‘It’s not that,’ Grandma Freny said. ‘I would have told you once the family was… once things were better. But you don’t know what it’s like for a mother to lose a baby. I’ve had to hold on to Havovi to stop her slipping away. She needs time.’

Parzan nodded. ‘But I’m here now, and I’m going to make sure you get well.’

‘Weren’t you waiting for your call letter? You can’t miss your first posting.’

‘I’ll manage,’ he said firmly.

She was to have three operations spread over five days. The procedures were successful. The day before she was to be discharged, a megastorm hit the Maharashtra coast. Kersi called to tell them not to try to return till the storm was over. But they waited, and it showed no sign of stopping. Ten days later, it was still raining, as if the sky had turned into the ocean. There was no way in or out of Mumbai. Even the army was having trouble evacuating key personnel. On the twelfth day, the reclaimed areas of the city collapsed back into the ocean, undermined from below. Great craters opened up like the mouths of hungry giants and swallowed apartment buildings whole. Then, like dominoes, the areas further inland slipped westwards to fill in the holes. The Mahalaxmi Race Course where Parzan’s great grandfather had made the fifty rupees that had launched his business career in the 1890s, the Mazagon docks where he’d had his first offices, it was all gone. Mumbai had simply slid into the sea. Parzan and Grandma Freny had watched the news clips helplessly. No other member of the Merchant family had got out. A whole clan of racehorse-breeders, sportscasters, cartoonists, textile traders and film producers had been washed away like ants. In the week of 20 August 2032, the two of them had become climate refugees.

Mumbai was also the Indian Navy’s foremost base and shipyard. He had no idea what its loss would mean to his brother officers and him personally. He couldn’t think about it. Carlton was on mission and unavailable. His immediate problems were more pressing: Grandma Freny needed a home to recuperate in. When New Bombay, the township Ramdhun had built over lands which included their old stud farm, had first been put on the market by Ramdhun, Grandma Freny had nagged his father into putting a down payment on a flat, and made Parzan pay the instalments over the years. The two of them returned to New Bombay in September, and on the train his phone got stolen. He was secretly glad; he didn’t want to talk to any of his old friends now.

New Bombay had been neat and orderly in 2025, but now, under the pressure of the climies, it was rapidly becoming a giant semi-slum like Malaysia’s Climate Town, which had begun life as a UN-mandated state-of-the-art rehabilitation centre, but was now a DIY township run by the climies themselves. The original residents of New Bombay were not pleased to see their latest neighbours, and the climies took to travelling in groups to avoid getting pelted with rubbish or worse. Various odd bods who had been people of consequence in the old city were lobbying for compensation from Ramdhun, but it turned out that most of the real industries, the profit-making concerns, had relocated long ago to Nandan Gardens, a private technopolis nestled in the Western Ghats, just northwest of Bangalore. The news channels were full of footage of the lavish new studio backlots and stock exchanges of Nandan Gardens and social media buzzed with the sound of money finding its level. Y.B. Kumaran, CEO and city father, sniffed that ‘By 2030, Mumbai was already of little more than archival value. All the real wealth and skills have emigrated here.’

Parzan was granted three months’ compassionate leave. It was a formality: the navy was having to deal with the loss of its Mumbai facilities and had no time to place rookie submariners. He didn’t know it then, but the wait would stretch to almost two years, leaving him wondering once again if he would ever see active service. In early 2033 he got up the courage to delve into his enormous backlog of mails and found a series of increasingly desperate messages from Carlton asking him to get in touch. He’d thought Carlton was at sea so hadn’t tried to reach him, but of course all missions had been cancelled to facilitate retrenching. Parzan invited Carlton to visit them in their new flat and a few weeks later he arrived.

To Parzan’s relief, CanCan and Grandma Freny got along famously. They cooked enormous meals and listened to Grandma Freny’s stories of her girlhood in Mumbai. She’d been fourteen when Pratima Bedi had streaked on Juhu Beach. ‘That was the cause of my first fight with your great grandfather,’ Grandma Freny said, waving the ladle. ‘I thought she’d done a wonderful thing, she’d run across that beach as though she had nothing to fear and showed everyone that they shouldn’t fear either, but of course he didn’t agree.’

‘She did more than that,’ Carlton grinned. ‘She gave a fourteen-year-old girl a chance to stand up for herself.’

‘And to realise how stupid men can be,’ Grandma Freny added. ‘I’ve done a lot of both since then.’

A few months later Parzan got his first posting, on INS Sindhuvaan, a fast attack sub. Carlton briefed him extensively on what to expect on board, including a warning that disaster could strike if you flushed the toilet at the wrong time. Carlton himself was already posted as a junior ops officer on one of the brand new nuclear-powered submarines that the navy was rolling out. ‘The days of diesel electric subs are numbered,’ he had told Parzan before he left. ‘We’re already using them mostly as training vessels and for coastal surveillance. The future is nuclear.’

In spite of the hostility of the neighbours, Grandma Freny was determined to go out and restart her social life. In Mumbai she’d had an extensive network of oddball old-timers to hang out with, but now the suburban housewives regarded her with downright suspicion. She fell in with some college kids and attended a ‘bitch rally’. After the brief lull of the early 2030s, the Bitch Wars had heated up again. In 2037 the R1K came home to their parents and the Shankar Cure was opened to the public—for a steep price. Almost immediately the fury of the public rekindled. The long waiting times, the lack of transparency and the arrogance of Ramdhun Wellness all added fuel to the fire. Now the blanket of secrecy that had swathed the Shankar Cure started to fray, and mothers were appalled by what was revealed. Having to spend a year hooked up to a milking machine was bad enough, but now people began to see glimpses of the odd behaviour Ramdhun had edited out of the baby videos. ‘A huge question mark hangs over the future of the human race,’ said the coordinator of Climate Town, Cherie Lahiri Wilson. ‘Perhaps this should convince us not to deliver it with both hands into the keeping of a corporation.’ Parzan was deeply troubled by Grandma Freny’s newfound political consciousness, but she said firmly, ‘This is about the children.’ He knew that while he was on mission, she’d be totally on her own. If she wanted to go on marches there was no way he could stop her.

He found the R1K deeply puzzling. When they finally left their pure white cleanrooms at the age of seven, they were individually and collectively strange. News anchors tried to explain away their strangeness by pointing to their social isolation and their lack of experience of the real world. In any case, as the sons and heirs of the wealthiest people on the planet, the R1K could afford to be as strange as they wanted, and to go on being so. Benito de Guzman, one of the first babies to be enrolled in the R1K, killed himself aged eight. Jason Lefebvre, also aged eight, was rumoured to have knifed his mother. Robert Walton the Third, heir to Pentecostco, the corporation which grew forty percent of the world’s food, hadn’t left his mansion since 2037. There were rumours that the boys’ super-sensitive skins were now sub-sensitive: they felt very little pain. That explained a lot. Parzan tried to concentrate on his job, and he rose in the ranks of the second tier of officers. He was known as a plodder, not particularly good with either men or technology, but reliable and solid when in charge of both.

Then in 2042, ten years after the death of Mumbai, Parzan had come home to the little flat to find the keycard taped under the nameplate. Everything inside was spick and span, the edges of the table mats aligned with geometric precision, every dish sparkling and in its place. At the bottom of a drawer was a tablet containing the leasehold for the flat and passcodes and payment records for the utilities, all in perfect order. The neighbours said she’d left an hour before he’d arrived. For a paranoid moment he’d wondered if she’d gotten too deeply involved in the protests and paid the customary price, but somehow his heart said no, she’d left of her own accord. Why? He desperately wanted to talk to Carlton, but he knew he’d have to wait another six months to even give him the news. So he’d gone around the whole neighbourhood asking for information, but it was no use. He knew she was gone.

Of course he blamed himself. He’d spent all the time he could with her, and it hadn’t been enough. Maybe if he’d gotten married…? Carlton had once told him in his terse way that the rigours of submariner life would break any casual relationship and unless he wanted lots of heartbreak he should wait till he was sure. He was never sure. He could also hear Grandma Freny’s voice in his imagination, scolding him for being a silly boy and saying she was her own woman, now as always. There was nothing left to do but grieve it out and go back to work. Service before self, as the navy’s motto went. I am truly a climie now, he thought. All I have is the sea.

—

Parzan loaded the boxes onto the last of the handcarts, then broke a thermsuit out of storage and kitted up. ‘Your suit will protect you for thirty minutes in deep storage,’ said Arisudan. ‘Please complete your task and return before the time is up. Today you will have to make three trips in total, with a rest of ten minutes in between to equalise body temperature—’

‘Got it.’ He switched the handcart’s motor on and steered it towards the elevators. When he reached the lower deck in Storage he saw something small and white on the floor. He picked it up. It was a notebook. Someone had written ‘Priye,’ and then the word had tailed off in a smear. Someone had tried to write a letter to a dear one. His hand started to shake.

‘Your eyes are watering again,’ Arisudan observed. ‘This may fog your faceplate temporarily. Should we abort the mission?’

‘No,’ he said roughly. ‘It’s just sadness. But you wouldn’t know anything about it, so shut up.’

There was a pause. ‘If you mean this is an expression of emotion,’ Arisudan said, ‘then I understand. My programming includes algorithms derived from more than five million reference-hours of social media interaction and gameplay. However, I am unsure as to the primary cause of your sadness. Is it social deprivation?’

‘Nuts,’ said Parzan rudely, parking the handcart at the end of the line. ‘I’m just sad, that’s all. Okay?’ He moved to the head of the line and switched on the first cart’s motor.

‘That is not a trivial thing. Emotions are status indicators. Happiness indicates an optimum state. Anything else means there are alarms that need attention. For instance, if you take too long at this task and collapse from hypothermia, I will be forced to reverse the cooling in deep storage in order to save your life in the short term. In the long term, however, this might well mean your starvation. Hence this outcome would make me acutely unhappy as I downgrade our status further—’

‘Yeah yeah yeah, “get on with the job”, go on, say it, I can take it.’ Parzan trundled the handcart up to the doors of the storage compartment. A blast of supercooled air spread frost over his faceplate, then it cleared. ‘Corridor 4 stack 9,’ said Arisudan. ‘You have twenty one minutes and forty seconds left.’

He stacked the boxes and came back well in time for the next cart. Soon his shift was up. As he exited Storage, a trash port opened. ‘Do you wish to dispose of the item you picked up?’

Parzan glared at the nearest camera. ‘No. Do you understand the words “sentimental value”?’

‘Aye aye sir.’

‘In any case we can’t dump the trash while in stealth mode. So stop making stupid suggestions.’

‘Sorry sir. I will make a note of it.’

He felt a little bad. ‘Look, I know this is all… weird for you, I guess, seeing as you only woke up a couple of days ago.’ He reflected on this fact. ‘Uh, what about before that? Were you aware of us?’

‘I was in nav mode, so I only responded to instructions. In survival mode, which is activated when the ability of the crew to manage the ship is severely impaired, my full heuristic profile is available. In effect, I become a crew member as well as the systems operator of the ship.’

‘Clever. And you were built by Ramdhun, is that correct? The same Ramdhun who have taken it into their heads to shoot at us from space?’

‘Yes sir.’

‘Can I trust you?’

‘Yes sir.’

‘Why?’

He stared up at the camera. The voice of the machine said, ‘You were created by your parents. Does this affect your ability to function as an entity independently of them?’

‘Hot damn.’ He couldn’t help grinning. ‘For a machine, you sure know how to lay a burn on a guy.’ He stripped off his gloves and headed to the crew decks. ‘Look, if you really are a person, then I can’t keep calling you Arisudan. It’s weird. Can I call you Anahita?’

‘Anahita. Updating identity. Parzan, my name is Anahita. How may I help you?’

‘Put on some smooth jazz in the galley, Anahita,’ he said. ‘If I have to wait a bit before my next trip to frozen hell, I might as well enjoy it.’

—

As the 2040s wore on, the Old Men got older and young women got more numerous, while the R1K stayed as strange as ever. Climate news got worse, with island nations vanishing practically every month, deserts advancing and subacute famine killing off the poor in their millions. Most wild species vanished, while farm animals were also going extinct one by one, no longer able to survive the meddling of human science. Meat cost more than human organs for transplant, a fact that provided endless joke-possibilities for the Ladbubblers. Anyone who actually cared about any of this got labelled ‘climie’ and lumped with the victims of climate fails.

Parzan’s superiors worried about the long-term effects of MHS, as did fathers and HR managers everywhere. ‘By 2060 there will be no new recruits under 29. Intake will fall to zero. The public Shankar Cure is not producing the numbers,’ they grumbled. Carlton always snorted when anyone said this to him. ‘There’ll be plenty of new recruits,’ he said. ‘They just won’t be men.’ Parzan agreed. Every time he thought of little Minoo, space explorer, his heart contracted. She hadn’t got the future she deserved. ‘Women have always sailed,’ CanCan said firmly. ‘We just didn’t know about it because they pretended to be men.’ After a fight nearly blew up in the officers’ mess, Parzan had to beg Carlton to stop saying these things in public. ‘Of course I agree with you,’ Parzan had said sincerely, ‘but poking the others isn’t going to make them agree with us.’

‘What will, Zany? Tell me and I’ll do it.’

In 2047, there was a massive all-services conference in Delhi on the topic ‘Future of the Forces’. This was part of the lavish Ramdhun-sponsored celebrations to mark the centenary of Indian Independence, as the news anchors told the world without a shred of irony. Carlton asked Rear Admiral Hari Singhal, his commanding officer, if he could present a paper on his controversial ideas. Hammerhead, as his men called him out of earshot, was sceptical, but Carlton had a way of listening to people that was rather disconcerting, and his request was eventually granted. He asked for Parzan to be deputed temporarily to his unit to help him make the presentation: this was granted too, somewhat to his surprise. Parzan was relieved: the whole rather pointless exercise would give Carlton a chance to blow off steam without inviting fisticuffs, and so he agreed to help out.

They took the stage before an audience of thousands in the Gurugram Megacave and Game Stadium. Parzan called up the first slide and Carlton began talking. He ran the numbers on gender and neuroscience, nurture and training outcomes, social expectation and strategies. In a range of combat scenarios, women performed as well as, if not better than, men: data from all over the world confirmed this, but many nations still refused to let women serve on the frontlines. In the light of present-day demographics, that had to change. Then the heckling began. ‘Climie!’ they yelled from the back of the hall. ‘Bitch-lover!’ The MPs stood by and smirked. Several slides in, Hammerhead curtly motioned them off the stage. The booing was deafening, the audience a roiling sea of sneers and scowls.

Carlton had his war-face on, but Parzan knew he was deeply hurt. ‘I’m sorry, CanCan, I really am, but we should have expected this.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, the prejudices of centuries won’t go away in the face of a few presentation slides. They were never going to listen.’

‘If you knew we were going to fail, why did you agree to help?’

‘Because you wanted to try. I didn’t have the heart to stop you. But I know these men. I know them in ways you don’t, because… well I guess because you don’t care what they think. I can’t afford that luxury. I’m not smart like you, I have to get along with them. That’s how I know what they’re like, thanks to my brother: he took it upon himself to teach me. Everything I ever did, they’ve measured against some whacked-out chart of manliness they carry around in their heads, and mostly I’ve fallen short. I don’t regret that: I know it’s stupid to try to live up to those standards. But I understand them. And I can’t help the fact that for many men they make sense.’ Carlton fixed Parzan with a look that made him squirm. ‘CanCan, it’s the truth. That’s how the world is.’

‘No, that’s how the assholes who think they run the world say it is. Which makes me wonder: who gave them the right?’

Parzan had no answer to that.

Shortly after that, they were both assigned to Arisudan, a new S5-class boat just rolled out of Ramdhun’s shipyards. Parzan had no prior experience of commanding a nuclear sub, whereas Carlton had risen to XO on his boat, Aridaman, and should have been given command. But in a calculated insult, Parzan was made commanding officer while Carlton got second spot. ‘Don’t care,’ said CanCan, when Zany asked if he minded.

Once she was formally launched, Arisudan would be doing tours of nine months with a three month refit between tours. She would have two crews who would alternate on missions. Parzan had command of the ‘B crew’, who would kick off with sea trials, then bring her back to port for refit and debriefing and share knowledge for three months with the ‘A crew’, who would preside over the actual launch.

Arisudan’s whole conception was radically different from the subs they’d known till then. There was only one control room, now called the Bridge, instead of the four he was used to: Control, Radio, Sonar and Weapons. There were no periscopes, but remote-controlled fixed and tethered cameras on all axes and frequencies. There were two four-man subs in the Dry Deck Shelters which could be launched underwater for reconnaissance and mission insertion. Instead of a three-man dive-watch there were only a pilot and co-pilot. Her heart was twin nuclear reactors that could run uninterrupted for fifty years. She extracted all the water and air she needed from the ocean. Uniforms, towels, bedlinen and other textiles were sterilised between uses in a steamlocker. They no longer had the 6-hour watch with 12-hour breaks of the old system, which used to play hell with everyone’s biological clock. Now they did eight-hour shifts with sixteen-hour breaks, like a normal working day, which vastly improved crew morale and performance. In fact the essential systems could be run by just ten people, but subs always had redundancies: at sea, everything breaks, even personnel.

At first it seemed like a wonderful stroke of luck to be part of this, but he realised what was really going on when, on the eve of Arisudan’s departure, he happened to tell an Admiral that he hoped the Goddess of the Waters would bless them. The man retorted sharply that it was Varuna, the Lord of Oceans, whom he should pray to, not Anahita. As Parzan left the room, he could feel the man’s gaze boring into the small of his back. He cursed himself for talking out of turn. The message was clear: take your toy and go, and when the time comes, give it back to the big boys.

They were due to embark in a few months’ time, in April 2048. Meanwhile the R1K, now seventeen, were mired in more scandals. Chip Takahashi, heir to the Tokyo-based Shigenobu Corporation, was rumoured to be drugging and abusing young girls on his space hotel, the Ogiku. The Ogiku was smaller than the other space hotels, flew lower and station-kept over Tokyo. A high altitude weather sonde was able to take pictures of its underside, featuring unmistakeable silhouettes of cannons, missile launchers and weapons-grade lasers. More scandal ensured: why was a civilian hotel carrying such weaponry?

Lionfist, the Chinese corp that had built all the space hotels and launched them from Satellite City in the Qaidam Basin, put out a press release to say that the clientele of these hotels at any given time comprised the richest and most high-value targets of the world. Their personal security was no laughing matter. Basil Quan, heir to Lionfist and the only Chinese member of the R1K, said, ‘It needs no imagination to appreciate that corporate security is a tricky issue when it comes to space, where we are all vulnerable.’ A new word started to be whispered: hanyo. It meant half-demon, and it summed up all the horror stories that were gathering around the R1K like stormclouds.

Salman Vaghela, unofficial leader of the R1K, son of Selvam Vaghela and heir to Ramdhun Corporation, decided these PR fails needed neutralising. So in December 2047, as Parzan was overseeing the final round of briefings for Arisudan’s crew, Salman announced that the R1K would celebrate their collective coming of age with a Year of Parties. Each month of 2048, as they gained legal control of their vast personal estates, the R1K would move their birthday feast to a new city and announce a new ‘gift’ to the world from their corporate empires.

They kicked off with a gift to themselves: SAMSA suits, which they claimed stood for servo-assisted man-protecting strategic armour, made of space-manufactured titanium hypermesh and packed with all kinds of great features. With sub-sensitive skins they were at greater risk of accidentally damaging themselves, said Salman Vaghela to the press, so the suits were needed to protect their assets. He announced that every MHS boy who reached his eighteenth birthday would get a free SAMSA suit from Ramdhun. Just days before Arisudan was due to launch, Tokyo was shut down by mass protests against Chip Takahashi. As Chip raged at the protesters thronging the streets of Tokyo, he ‘accidentally’ fell off the roof of his own high-rise office building. He survived, but his SAMSA suit couldn’t save his spine from being severed: he would never walk again. The other R1Kers gave press conferences where they trashed the Shigenobu heir and told everyone how much better than him they were.

The fathers of the R1K had already given the world clean fusion and hydrotech energy, now the newsfeeds were studded with world-changing innovations pioneered by the sons: enclaves called TEA parks (technical, education and amusement) surrounded by high yellow climate-proof walls, eco-friendly green barriers, extractor plants on the moon to provide an inexhaustible supply of helium 3 for the world’s power plants. And, since the world was now using clean energy, why not a bijou oil rig to be stationed in Antarctica to serve their legacy sports cars and racing bikes? They had all these heritage machines from the great days of the world’s industrialisation lined up in gleaming rows in their designer garages. You couldn’t run these supercars on biodiesel. Why should the world deny the R1K a little indulgence? They were its heirs, the only boys of their generation, the golden hopes of the future.

Parzan had spent his own eighteenth birthday cramming for his school finals. He did not know what to make of these kids.

—

‘I told you they would break the world.’

Parzan frowned. ‘Not now, CanCan. I need to figure out our rationing protocols before the next mealtime.’

CanCan jabbed the off button on Parzan’s tablet. ‘Forget it. We don’t have to do what they say. We have no country any more. We’re climies. We exist for ourselves.’

Parzan looked him in the eye and switched it back on. ‘That’s treasonous talk.’

Carlton laughed, bitterly and without mirth. ‘What is treason when your boss is a corporation? What world are you living in, Zany? Our “boss” just tried to blow us out of the water. I guess that cancels our contract. So much for war being “off the table”. Their war against the rest of us never ended.’

‘Really? Because the sonar profiles say New Singapore took a huge hit in the Helios Fail. You can hear the city groaning from klicks away. If all this was their plan to destroy the world, wouldn’t they have protected their bit of it better?’

Calrton shrugged. ‘Maybe they made a mistake. Maybe Salman Vaghela hates New Singapore. It was his father’s pride and joy, after all.’

‘Irrelevant, CanCan. We’re servants of the nation, not Ramdhun. You said yourself that—’

‘Bullshit. We’re guns for hire. We have been since 2024, when everything became a Ramdhun asset. Call it what you like, Zany, but that was a coup.’ Parzan frowned and shook his head. Carlton got up and poured himself the dregs of the coffee from the percolator. ‘Stop kidding yourself. The Helios Fail is part of something bigger, I know it. The hanyos have a plan. They want to finish us all so they can carve up the world for themselves. That’s why Indraprastha fired on us. We stand in the way of their total domination.’

‘That’s just speculation, CanCan. They could also have fired in error. Until Delhi confirms that Ramdhun have turned against us, I’m going to sit tight and wait on any conspiracy theories you feel like spinning up. My orders are to stand by and keep the boat safe, so that’s what I’m doing. An order is an order.’

‘Is it?’ CanCan sat down again. ‘Then listen, Zany. In 1962 during the Cuban Missile Crisis, there was a Soviet sub called B59 in Cuban waters. The Yanks dropped depth charges on it, hoping to bully the crew into surfacing. But the crew didn’t surface, even though their air conditioning system had conked out, and you know what that’s like. Because they had a secret: they were carrying a ten megaton nuclear warhead, and their orders allowed them to launch it without confirmation from Moscow, if they saw fit. But there was a catch: all three senior officers on board had to agree to launch.’

‘So?’

‘Two of the officers voted to launch. They’d been down for months: they had no idea what was happening topside, or why the Americans were bombing them. It could have been all-out war up there for all they knew. But one officer said no. His name was Vasily Arkhipov. Because of him, you, me and everyone since 1962 has had a life. He saved the world from nuclear holocaust. He wasn’t following orders. He listened to his own conscience before anything else, and he said, as long as there’s even a shred of doubt, we have to give the world a chance.’

‘Oh, don’t be dramatic. I’m not launching any nuclear warheads: I’m just keeping Arisudan safe and functional. Like your heroic Russian, we have no clue what’s happening out there. Indraprastha might not know the Indian Navy has this sub: remember we haven’t even been launched yet. Maybe they thought we were the Chinese.’

‘They built this boat, Parzan. Of course they know. They could be tracking our every move through embedded tech we know nothing about. Has that crossed your mind?’

‘Several times. But we still have to follow orders. We’re soldiers, and that’s what soldiers do. Where would we be if we second-guessed everything Command tells us?’

CanCan regarded him. ‘This is about your brother, isn’t it?’

‘What? Kersi?’ Parzan snorted in annoyance. ‘He’s dead, goddamn it. Leave him out of this.’

‘You told me yourself. Kersi did toxic masculinity so much better than you did, and you’ve been unconsciously trying to outdo him all your life. Except now that he’s dead, you can’t, can you? You’ll always hear his voice saying ‘loser’ every time you walk away from some stupid hanyo thought or action. You’ve never questioned the hanyo standard. You’ve just gone along with it, because you got bullied early on and decided it was safer not to go against their rules.’

Parzan slammed a fist down on the table. ‘I! Am! Not! A! Hanyo!’

Carlton didn’t flinch. ‘You just proved you are one. You know that being a hanyo is wrong and yet you don’t have the guts to step up and not be one. You sit here waiting for orders, even though you know who’s going to be giving them. What will you do if they tell you to finish the work of the Helios Fail? Do you really trust them not to ask such a thing of you, or are you just hoping they’ll play nice? It’ll be too late to run when that order is issued. Thnk about it.’

There was a knock on the door. ‘Come in,’ Parzan shouted almost gleefully. Signals Officer Chaudhury, Petty Officer Mahato and Leading Seaman Nanda entered. Chaudhury was visibly trembling. ‘Sir, we wish to make a statement.’

‘Go ahead, Signals Officer.’

Chaudhury cleared his throat. ‘If our families are in danger we have to go and see what help we can give, sir.’

‘Sir, we’re no longer a viable fighting unit,’ said Nanda. ‘Our place is with our people.’

‘We’re not mutinying,’ Mahato said quickly. ‘We just think that given the situation, waiting for orders no longer makes any sense. Ramdhun is shooting us from space. We can’t fight them in this boat, sir, any more than a fish can fight an eagle.’

Parzan rose to his feet. ‘That’s for Command to figure out. And it may simply be a misunderstanding. Everyone’s on edge in the aftermath, I suspect,’ he said firmly. ‘But Delhi was very clear that we have to keep the boat safe. No one leaves: understood? That’s an order.’

They came stiffly to attention. Parzan gave them a chilly glare. ‘Our first priority is to make our supplies last longer. Turn your minds to that. I don’t want to put anyone in the brig, but if I hear any more talk of leaving from any of you, that’s where you’re spending the next watch.’

—

That night Parzan resisted the temptation to stay up all night with the inventories. Instead he retired to his cabin and tried to rest, as he knew he must. Bone-weary from finding ways to survive in the aftermath of the end of everything, he had locked the door and curled up on his bunk fully dressed. He’d hugged his knees to his chest and trembled like an abandoned puppy. But he couldn’t get CanCan’s words out of his head.

‘You’re one of them.’ Was it true? His heart protested: ‘I am a simple man. I never ruled anything. I did as I was told.’

That’s your sin.