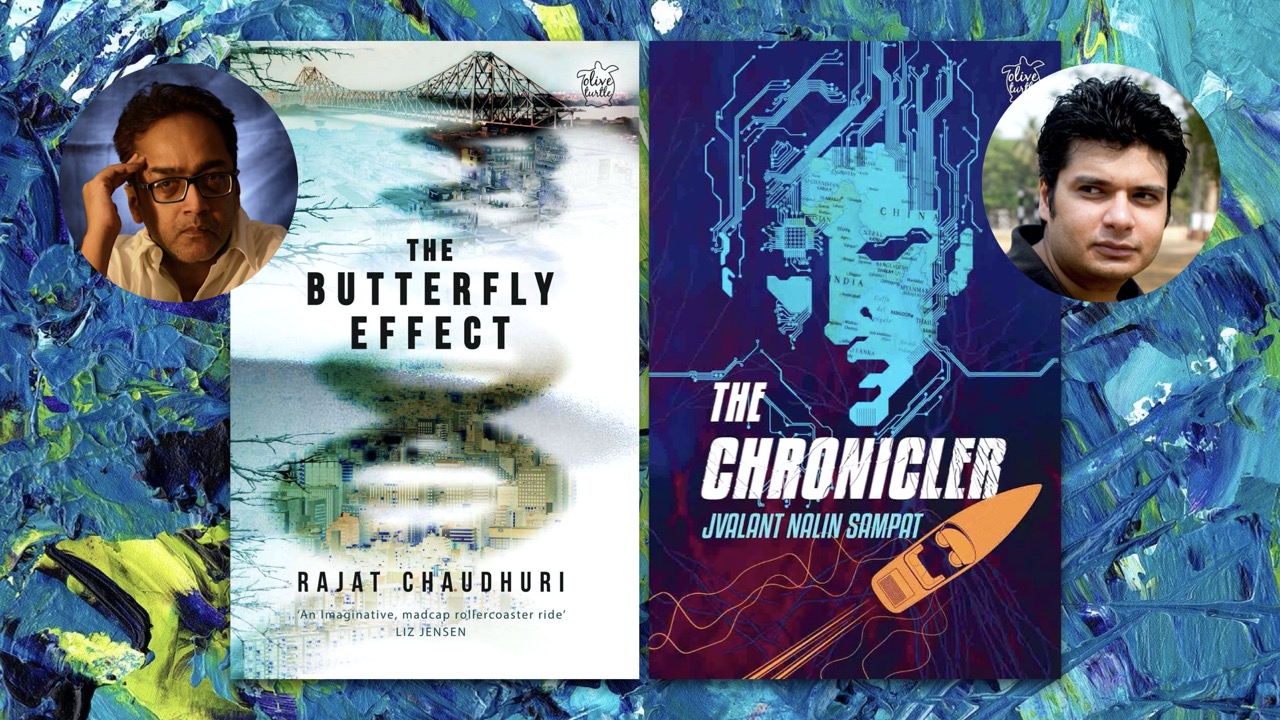

Rajat Chaudhuri and Jvalant Nalin Sampat discuss science fiction (“sci-fi”), cli-fi (climate fiction), solarpunk, classic sci-fi films, and their respective books: The Butterfly Effect and The Chronicler.

Rajat,

Nice of Salik to arrange a round table like this. Seems you’ve already had quite a journey. I am just wading into these waters. Personally, I see stories set in a backdrop—don’t necessarily see them as sci-fi, or speculative fiction; this new term seems to have gained a lot of currency lately. I just like to select an era as a backdrop and use it as a canvas to paint a story. How do you go about your craft?

I try to tell stories that age well. So it is with trepidation that I venture into something like sci-fi. 2001 A Space Odyssey and Back to the Future come to mind. The former had public telephones and moon bases by 2001 and the later had fax machines and flying taxis in 2013. Do you worry that your science fiction will not age well? Not that these haven’t—they are still enjoyable. But not everyone is an Arthur C. Clarke. How do you see someone picking up your sci-fi work—20 years from now or even 30? Some of the memes these days show 2050 as distant from 2020 as 1990 is and that kind of makes you think about these things.

Another aspect of writing sci-fi I find fascinating is that many writers assume that there will be a more liberal society in the future unless you are writing something utterly dystopian. You see writing from the 90s and earlier and you see space travel, equal rights irrespective of sexual orientation, leaps in medicine. But looking at this current Modi-Trump world we live in, perhaps we should explore more of a dystopian future? A lurch to the right is quite apparent in most societies. Do share your views.

*

Thank you Jvalant,

Let me thank Mithila Review and Salik for arranging this. It’s an honour for me, more of a mainstream literary fiction writer (at least that is how it has been till the last two books) to be invited by one of the well-regarded speculative fiction journals from this part of the world to discuss our work.

To get directly to your question about craft—I believe there are two parts to this, really. First the jumping-off point, where you launch into creating a new work and then comes the arduous, day-to-day, fashioning of character, settings and scenes while also keeping a lookout for the plot so that it doesn’t get too much of a life of its own, totally disregarding the creator or her subconscious. Though that is important too at least in certain stretches of the process.

For me each book started differently. There was almost always a distinct image, a strong impression, a person or an overlap of these that propelled me towards this madness. Then again the experience one gains from living have an important role to play. I have been an environmental activist for donkey’s years; I still am involved with climate change and sustainability work which, as you can well guess, can be fulfilling and frustrating in equal measure. But in course of these engagements, I’ve had the opportunity to travel widely and meet a wide swathe of people from different nationalities. I have always thought about using this rich and diverse experience creatively. My first novel (Amber Dusk) was essentially a fruit of this engagement and so was my latest but in a very different way, of course. In my most recent novel (The Butterfly Effect), which has been variously dubbed as sci-fi, cli-fi, speculative or biopunk, I was trying to visualise my activist work through a creative lens—not in the sense of the experience of activism and meeting people and creating characters but as a different means to engage people (here the reader)—about the dangers posed by science without precaution and a neo-liberal order that is anchored on growth for growth’s sake disregarding people, lives and the planet.

There has been another great driver of my creative output and that is the city of Calcutta/Kolkata where I live. For many years now I have been reading and experiencing the city through books, aimless wandering and purposeful exploration. There are elements of the flaneur’s ambivalence here but there is also a deeper interest to know the city through its characters, especially dark, marginal, almost gothic characters. I have made friends of them and have been in some very interesting situations. They distract me from my creative work but without these friendships and without the dust of Calcutta sticking to my boots every day, I guess I wouldn’t have written much. Two of my books—Hotel Calcutta and the most recent Calcutta Nights, a work of translation from a Bengali mystery writer’s nocturnal wanderings, with shades of gothic and pulp, in the first decade of the 20th century—are both fruits of this Calcuttaphilia. Perhaps the fact that I also write in Bengali and have been much influenced by the literature also feeds into this special relationship with the city. A kind of osmosis between the two languages and the literatures that define my choice of subject, characters, style and more.

This connection with Bangla literature feeds into an interest in speculative fiction for as you know Bangla, Urdu and some other languages have a strong speculative tradition right from one of the first sci-fi stories written by the scientist Jagadish Chandra Bose to Premendra Mitra, Satyajit Ray, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay and many more. Which brings me to your comment about ‘speculative fiction’ as a category gaining currency. I feel it’s a good thing as spec-fic is an umbrella expression covering all kinds of work, in a variety of mediums that goes off at a tangent from the real. We are not only looking for Darko Suvin’s novum here but looking much beyond and basically challenging European enlightenment’s dalliance with reason and modernism’s partitioning project which kept everything from mysterious powers (like your Nine Unknown Men perhaps?) to the non-human world out of the halls of ‘serious’ fiction. Would you say your work has this problematic relation with ‘reason’? Does it jettison the verisimilitude pact of modernity, and if so, do you feel concerned that writing such stories could push your work into the ghettos of what is called ‘genre’?

Your question about sci-fi aging well or not is very interesting as this has implications for the kind of speculative/sci-fi work I have written (The Butterfly Effect). I have been thinking a lot about this lately, especially in the context of climate and eco-dystopian fiction as a subset of sci-fi. In my activist circles there is a clear understanding about the need to write hopeful futures and keep dystopia at an arm’s length. Many believe dystopian depictions can immobilise people draining their energy to act. On the other hand scholars like Keira Hambrick hold that readers have genre expectations and can easily filter the dystopian element, drawing their dose of enjoyment from it while not ignoring the message of a cli-fi novel. I have come across interesting empirical ecocritical studies of climate fiction where it has been found that the characterisation and vivid settings of a climate ravaged world that connect more with the reader, also the reader’s political leanings (liberal, conservative, etc), but not really whether it is dystopia, utopia or something in-between. In my case, I am looking forward to creating works about positive futures and in this context must tell you about this interesting Asia-Pacific solarpunk anthology for which I am reading stories right now.

However to think beyond this activist intention, which one can never quite abandon, and so on and thinking of all kinds of speculative fiction I would say the reader’s enjoyment is paramount. If flying cars appear over Delhi in 2010 so be it as long as the reader is happy. However, sci-fi authors, many of them, I suspect have a secret urge to be successful futurists and so they have this desire to guess it right and this in its turn has bred interesting `Who was right’ comparisons like the one between Brave New World and 1984.

I am intrigued by the plot of your novel. With Nine Unknown Men, was it the Morning of the Magicians where I read about them first? First I must tell you a secret. I finished a novel sometime ago, which is a sort of urban fantasy set in modern India (Delhi and Calcutta) and these Nine make a cameo appearance there! Because of getting busy with other projects I never quite completed or polished it but with the success of your book I am thinking about it again. That aside, do tell me about your research. How did you chance upon the story of the Nine? I must say plots like the one in The Tenth Unknown brings to my mind two very different writers—Dan Brown and Umberto Eco. Do you complete your research before beginning to write or you continue parallelly till some distance? And if you go for the latter does the research have an impact on the plot that you may already have in your mind? Do you have a very definite plot right from the beginning or just know some goals that you have to reach?

*

Thanks Rajat.

That was a pretty intense read. I must confess I had to look up the word “verisimilitude”.

But then again, you are from Calcutta—one of the last bastions where English hasn’t been Americanized.

I have always been a bit of a history buff. So when I got the opportunity to work in a library as a tech assistant in the US, I happily spent a significant amount of time getting books from the history section. I learned more about India there than anywhere else. I went through old NY Times archives on microfilm and microfiche—a fascinating way to store history before the digital revolution kicked in. So my research for The Tenth Unknown unknowingly started a long time ago. But I wanted to be accurate while writing the book—so some research did continue in parallel.

I am not truly concerned about being slotted into a “genre”. In fact, I prefer not to be considered a “literary” author because I think with shrinking attention spans and the proliferation of NetFlix and Amazon Prime, literary writing is going to go the Kodak way.

As you said, the reader’s entertainment is paramount. You asked where I came across the legend of Asoka’s Nine Unknown Men. I don’t even remember. But it probably stuck me as entertaining and led to the first book. For The Chronicler I did make a conscious decision to eschew chapters and kept my sentences short and the language accessible. I think the crude term is “idiot proofing”. Do you make a conscious effort to do that or you don’t compromise on your prose?

Also, I’ve never spoken to someone who is a bilingual author. If you had to write the same story in both English and Bengali—which language do you think would do more justice to your thoughts?

I’ve always known Bengali literature is very rich (my Mom’s from Calcutta) and I guess there must be some great speculative fiction in various other Indian languages as well. It is my loss that I can’t read any works in Indian languages. I avoid reading translations—something is inevitably lost.

Let me know if you are ever in Bombay, it would be great to catch up.

*

Jvalant,

Apologies for the delay in getting back this time. I just published a book and have been working with a group on a solarpunk anthology so time management just went out of the window.

I guess we have different ideas about making our stories accessible to the audience which of course goes with the corollary, what kind of audience we are looking at. Though it might sound elitist to certain people, I am not much for watering down the language to a sort of lowest common denominator or using the Flesch–Kincaid readability test on my story, because I believe a larger and varied palette of words (colours in case of artists), a distinct style and so on makes the final work (the painting) more appealing to the discerning viewer. Literature is about exercising the mind and the reader’s involvement in the work of imagination is part of its appeal. Literary construction, as well as a larger written vocabulary, just adds to this magic. In this I lean towards ideas of Will Self (In Praise of Difficult Novels) and others.

However, this is not to say that the complexity should be an end in itself. Given my theme, story and the depth of the characters, this process can be calibrated as required. I must say I have been a fan of Hemingway and Carver and all those wonderful hardboiled detective fiction produced in the West where the language often flows smooth like a river. Hemingway, of course, was trying to do it consciously, and in that he was somewhat like Paul Cezanne in art, who asked us to see nature ‘just in terms of spheres, cylinders and cones’.

However beyond all this, the story is paramount and I am not much for the modernist tendency of lingering and prefer faster travel even if it be through a complex structure.

If I may return to the Nine Unknown Men in your first book, I am curious to know whether you found any connection between them and the so-called Navaratnas of Vikramaditya’s court during your research. Could it be that the Navaratnas legend was taken up by Talbot Mundy, Pauwels, Bergier and others and repurposed as the Nine Unknown Men in their stories?

As you mention, the OTT platforms like Netflix are no doubt having an impact on how words are produced and consumed. However, I am not ready to believe these will spell the death knell for literary writing. I believe the novel is a powerful and very adaptive form that can metamorphose with the times but never die out. In fact, the death knell for the literary novel has been sounded many times in the past but this form proved highly resilient. But I do believe the novel and the story is undergoing and will continue to undergo major changes because of the biggest challenge facing humanity today—climate change. A bestselling novelist from the UK recently asked me whether I believe all novels in the near future will be climate novels or cli-fi. Well if things continue as they are and which is what looks most probable, then writers would find it hard to ignore this reality in their works. Also because of the amorphous, hyperobject like nature of climate change and its effects, the form of the novel is coming under serious stress and this is already transforming the creative work of many writers.

As this form is very adaptive, we find in the works of writers like David Mitchell, to give just one example, how the new realities of digital media are being adapted by literary writers. One change that literature in general is going to undergo because of these new realities, and this we already find happening, is the return of the serialised novels in the style of the nineteenth-century penny dreadful. Your new novel The Chronicler seems to have been consciously written for the screen, considering its cinematic aspects, as so many books are now being turned into web series and so on.

Thanks for asking the question about writing in two languages. I have given this some thought but of course I can speak only for myself. As you know, Marathi writers have a strong bilingual tradition among writers just as we used to have in Bengali but now not so much. I’ve often written and published stories in English, and then transcreated these in Bengali and published the Bangla story. Also I am now translating from Bengali to English and just published a new book Calcutta Nights which is an early twentieth-century real-life account of famous Bengali author Hemendra Kumar Roy’s nocturnal wanderings in forbidden and dangerous places of the city. A translated poetry collection is next. But do you really think it’s not worth reading translations as something is inevitably lost? Well, I believe something new is created and while a little might be lost much more is gained. Are we really able to express our innermost thoughts and feelings exactly to the next person in any language? We cannot, so something is always being lost but our minds, perceptions and language compensate for it in beautiful and human ways.

To answer your question, I have found that I am more comfortable writing humour in Bengali. When I write in English, quite unconsciously, I tend towards national or transnational settings while I enjoy setting my Bengali stories in Calcutta and Bengal.

Yes, I will surely get in touch when I am in Bombay next time. It is such an atmospheric city and certain things about it always remind me of Calcutta.