I died as a mineral and became a plant,

I died as plant and rose to animal,

I died as animal and I was Man.

Why should I fear? When was I less by dying?

— Rumi

Being deprived of a dream is much more cruel than simply being shot and dismissed.

— George Saliba

The Crew

The crew of La Mariposa Negra had scoured the starless planet for days before the jinn told them the truth. The Akasharians were dead. They had been dead for seven millennia. Came in and out of existence in the blink of God’s eye. It was a moment of revelation.

The Captain

Lieutenant Najam Cortes stood outside La Mariposa, a neat line of footprints leading behind him to the ship like the footprints of a ciguapa. Minutes ago, the Shaykha had radioed out the news.

A grin crossed his face. In Dominican folklore, ciguapas were omens of death, mythical women with backward feet who’d walk from the ocean at night. This reminded him of the first evening he spent watching the stars with his father, lying on the cool sand of Dominico, ears cocked to the whisper of the sea.

“Look, Najam,” his father said. Young Cortes rolled his eyes and looked up. “People — they say they look, but they do not. Not truly. They fail to notice the immensity.”

As Cortes regarded the sparkling black, he wondered how many stars there were and how much more empty space there was. Was there life out there? This was a childish thought, he would admit eventually. In two dozen millennia, humanity had discovered nothing smarter than a ferret.

“Al-Ghaib,” his father murmured.

“Dad,” he protested. “English.”

“God, the Unknown.”

He and his step-brother, ship’s archaeologist Burhan Jimenez, idled away their early youth on that beach. They spent hours in the water and sand until the sun set. They’d lie on their backs and watch the stars each night with fresh eyes, waiting for an answer to drop from the sky until their eyelids drooped and one of them began to snore. Soon the sun would cast the night violet-blue in premonition of dawn, when birds would rouse them. The brothers would perform their morning prayers, attend academy, and return in the evenings to repeat the routine.

Nothing could climb from the ether, eyes searching, brains occupied with anything more than hunt, forage, mate, defecate. The corporate empire, Kradys, declared this a mathematical impossibility. They had explored enough of the uncharted space to know that the statistical probability of intelligent life was magnitudes of fractions of one percent. It may as well be zero. They had derived a mathematical proof for the Fermi Paradox and claimed the universe humanity’s absolute manifest destiny.

Or so they said.

Thousands of years of wishful thinking, despite the mounting evidence against it, that there was someone else out there — to end with this. At first, Cortes couldn’t believe it. Now, he’d stopped caring. He had come to save Paco Sol for the Shaykha, not for Paco, science, or the experience of first contact. He owed the Shaykha for her charity and the lives she saved in the war, including his own. She was honorable, and if Cortes lived by one principle, it was that honor was to be reciprocated.

Now he had completed his moral obligations. They were on Akashar. But the extinction of the Akasharians — the crew’s only hope for Paco’s survival — merely escalated Cortes’s frustration. Something more had to be done. This couldn’t be the end of their long journey, could it, the ashes of a dead civilization?

He surveyed the ambiguous remains of Akashar in La Mariposa’s meek light, his jungle-green suit crinkling like twisted aluminum. His large grey eyes, flecked with black, stared back at him from inside his visor.

Cortes knelt in the Akasharian ash and faced a triangular, black edifice overhead, then the grey smog above and the opaque debris behind it. The ship rested behind him like a coral reef doused in ash, wings sticking out awkwardly as if to catch heat from the cold. A hole occupied the debris overhead, a dark gap in the sky, a black mockery of the sun this world never had. In their desperation, the Akasharians had wrenched a peephole in their orbital junkyard so that as they perished they could glimpse the worlds beyond.

He stared into the probe’s camera readout in the periphery of his helmet. The probe hovered over the surface, climbing mountains and crossing fields of ash.

Something dark blue flashed across the screen. He inhaled sharply.

“I seek refuge in God —”

He switched the probe to manual and turned it around. There was something there, wriggling in the thin atmosphere of Akashar.

The Physicist

Inside La Mariposa, Arondi Maduro stared into the debris above and held Orlando Rodriguez. He paused, a pouch of Gliesean rum on his lips. He wasn’t smiling, Arondi noticed. He always smiled. He smiled too much. She was about to tell him this but stopped, watching as his face grew blank. She wished she were more than mildly satisfied with his change in character.

Arondi wanted to return to that age when people believed they would find a universe thriving with sentient life. They had just perfected cryogenic science, and everything had seemed possible. People listened for signals in every wavelength on the electromagnetic spectrum. They searched every star system in the Milky Way and half the next. They looked for patterns in nature, anything that could tell them another sentient race awaited. In the end they found white noise from the Big Bang; prokaryotic cells on Bashar; and algae in a few places like Europa, Lincei, Gliese 581g, and Santiago. Dominico once bustled with life, but Kradys had industrialized it into desert and mulch.

There was nothing. After twenty-four millennia, people concluded the search was a lost cause. Kradys wrote a predictive formula telling them so.

Of course, the Shaykha’s analysis revealed a small but significantly nonzero probability of sentient life elsewhere. It was something on the order of one hundredth, a far cry from Kradys’ magnitudes of fractions of one percent. Set the Shayha’s probability against the statistical enormity of the universe, and intelligent life seemed a lot easier to find. Kradys incarcerated the Shaykha on Gliese 581g to prevent her from rallying followers. Bad science, Kradys bureaucrats declared, was a cultural malaise. The crew could’ve stormed the prison, but the Shaykha had insisted on remaining in protest.

A decade later, her son, Paco Sol, came to the old crew. He told them he’d seen the strangest things. Something had infected him. No, infected was wrong. The jinn called it Champollion’s Foot. He was dying. They broke out the Shaykha, evaded the corporate fleet, and journeyed here only to find —

What was it? It wasn’t nothing. It wasn’t something. It was frustrating, anticlimactic. The weight of eons of human curiosity pressed down on the barrenness of this cosmic non-answer, as if Arondi had lived those billions of lives spent searching.

We are still alone.

“A star,” she murmured. She stared through the gap in the debris. “We always thought it would have a star.”

“You didn’t believe the observations from Dominico?” Orlando’s hot breath caressed her temple.

“I thought it was temporary, not a home world. Not their only home world. What kind of world doesn’t have a star?”

“Akashar,” he translated, “the world without light.”

Outside, La Mariposa’s light forged a path out of the dark. Only now, engulfed by this planet’s unending blackness, did Arondi understand the name. She had previously thought of light as the norm and shadow as anomaly. But here light was not a status quo eclipsed by its absence. Rather, the absence of light was the norm, accompanied by little but the faint luminosity of distant stars. All her years of study culminated with this moment of simple experience. It was almost embarrassing how poorly her research had helped her achieve this raw feeling of comprehension. The idea of vacuum was a concept now tangible, something not merely known but somehow, inexplicably, felt. Finally, she grasped the essential nature of the cosmos: an ocean of shadow eclipsed by anomalies of energy and mass.

The Engineer

Titanus “Tito” Fernandez sat in the middle of the engine room curled around his electric cigarette. The cigarette blushed red as he peered into the thermodynamic tank where the jinn idled. It was an incredible piece of machinery. Jinn, beings of smokeless fire, were perfect combustion reactions. No excess. When you stuck them in a ship’s ass like provisions in a cargo bay, you did away with half the thermodynamic inefficiency.

“Fuck inefficiency.” He winked at the jinn. They writhed in their cage.

These jinn had brought the crew of La Mariposa here, for what that was worth. Thermo tanks ran the damned corporate empire. Human rights? Shit, they weren’t human, were they?

This was when Tito experienced his epiphany. He snapped to his feet, strode to the wall opposite the tank, and turned to Burhan Jimenez, who was staring at a holographic diagram of the wastes from Akashar. Tito pointed at the diagram.

“It’s a long piece of shit, man.” Tito sucked on his cigarette. He frowned at Jimenez. “We had all these fancy ideas about first contact. We invade them. They invade us. We encounter by chance in deep space. We get each other’s signals. They make patterns out of stars, write messages in distant nebulae.” He pushed off the wall. “At the end of the day, all we find is their shit, literally — washed up in our backyard. These fucking wastes from Akashar. Like a Megalodon’s giant turd floating onto our cosmic beach. I mean, what the fuck?” He laughed again, a high, wheezing cackle. “Man. We’re dogs, sniffing each other’s asses.”

Jimenez glared at him. “Can you take anything seriously, Titanus?”

“It’s a shit-cloud.” Tito smirked, ignoring Jimenez. That pompous bastard. “One big-ass snake monster. Now we’ve finally arrived at the bottom of the drain, and all we found is the Mother Shit. Akashar.” He rapped on the tank, where the ghostly forms of jinn squirmed in their cage. “Eh, boys?”

The Psychiatrist

Orlando Rodriguez pushed from Arondi’s embrace. Tito liked to call them “star-crossed lovers,” regurgitating an antiquated phrase only the engineer seemed to understand. This era felt like an antiquated thing, immortal, obsolete, and perversely old. Somehow Tito’s epithet worked — Arondi, the daughter of a massacred revolutionary, and Orlando, the son of a military contractor, together at the edge of known space.

Arondi could flush her cheeks and tell him she loved him, but it was difficult for him to believe her. “Do you think this, us — is it pheromones?” she would ask him, straight-faced. “Are our feelings the byproducts of evolution?” He could never help but agree, the way she always asked it, lips open and wet. But today felt like the end of something, like he had to call her out before they each passed to another life.

He moved the pouch of rum from his mouth, the fermented alien algae bitter on his tongue, and took her hand.

“Pheromones,” he echoed from those long-lost bedside conversations. Arondi kept staring at Akashar, but her grip tightened. “So you think we’re animals?”

“It’s not an ugly thing.” She said it as if he’d called her stupid. Her eyes flickered over the unintelligible sprawl of Akashar, Cortes’s figure a dark green pinprick in the distance dimly lit by La Mariposa’s overhead. “Science is beautiful on its own. It doesn’t require meaning.”

“Beauty without meaning…” he answered. He wanted to tease her, but the words felt manufactured. The bleak landscape of Akashar seemed to latch on to every thought with an enormous weight, like the Higgs ascribing mass. The Midas of gravity, these ragged structures, these mountains of ash, that orbital junk obscuring their view of this side of the universe.

He rubbed her thumb. She flicked it and turned, facing him.

“Science is the only thing we know,” she replied. “You’re the psychologist. This should be obvious for you. We’re addicted to meaning… It’s nothing more than neurons firing. What we know is the only thing that matters, because it’s the only thing we have.”

He could see in her furrowed brow that she knew her reply was as vacant as his silence.

“So.” He gestured at Akashar. “Why do you keep staring?”

She looked into the black expanse, quiet.

Pheromones. He almost laughed. A relationship based on the concept that love itself could be parsed and understood — was that love at all? It was as empty as the planet before them.

He reached for her cheek.

“Look at me, Arondi.”

For many of Orlando’s patients, the stars not only inspired awe. They conjured the thought that maybe there were others with whom they might share the cosmic toil of consciousness. People dreamt this for millennia. After twenty-four millennia, people kept dreaming, but they knew it was that. A dream.

Arondi continued to stare through the hole the Akasharians had wrenched out of their sky.

“Look at me,” Orlando said.

“I’m looking.”

He struggled to retain his poise.

“We’re alone,” he told her. “That’s the truth. We have to live with that.”

She had the look of one who had moments ago suffered a revelation, experienced rather than realized an item of great portent that stood in the face of prior intelligence. Like the face of an angel who had experienced, if it were possible, the absence of God. Her skin was prickly against his fingers.

The Archaeologist

The moment the jinn from the Hydrogen Bridge relayed the news, Burhan Jimenez finally understood the images he had scrutinized for so many months. They were the physical illustration of the slow death of an ancient civilization. Arondi’s diagrams depicted centuries of refuse launched from Akashar, crossing the void like streams of cosmic bile. Now he knew, as a matter of conscience over mere fact, that it displayed the gradual extinction of an old race.

Tito taunted the jinn. “Eh, boys?” he was saying. How ironic for a man named Titanus to be so small. Of course, this was why people called him Tito.

Burhan ignored him and turned back to the diagrams of the wastes from Akashar. He followed the debris again and again through the display, trying to make sense of something dark and cosmic at the edge of comprehension.

The jinn made it clear, the Shaykha had said. The Akasharians were dead, bodies vaporized. They wouldn’t say why. This made sense. They couldn’t say. Jinn were animals, weren’t they? What more could they do than rely on basic information? They knew the Akasharians were dead the way a dog barks after the stench of a buried carcass.

He kept perusing the diagrams, as if to wring an alternate truth from the debris. The initial discovery should have fascinated him. And it had. But he now realized Kradys’ ideas lived so deeply in him that the thought of an alien was itself alien, surreal, impossible. The revelation of Akashar’s existence had ignited a brief if wary hope, but the Akasharians’ apparent extinction rendered that question moot and extinguished his excitement as quickly as it had arrived. Only the existence of a living species, a threat to Kradys’ manifest destiny, was capable of rousing those age-old flames that kept children up at night beneath the stars, as they had for Burhan and Najam on the Dominican beaches of their youth. During no other time in his life had Burhan felt this distinct conflict between the rational clarity of his academic fervor and what he now suspected was the absurdity of his preconceived notions, which until this point he had assumed as fact. They were ideas he had been told from a young age, so young it seemed he had always believed them.

Burhan rubbed his eyes and moved his fingers into the somber purple aura of the display. He tracked the sinews of waste from Akashar all the way to the edges of the corporate empire, to the tiny black globule that had infected the Shaykha’s son, Paco Sol.

The diagrams revealed the evolution of Akashar and its inhabitants. First the dust of planetary creation. Then the debris of soon-to-be space farers — “What kind of civilization is that,” he wondered aloud, “that it simply discards its waste in hordes? My God, what excess… ” Then the silver, geometric remains of what he assumed were battles. Then the moons and rocky planets the inhabitants had brought near Akashar. They had no diaspora. No one ever found Akashar, he realized, because the Akasharians brought worlds to their home rather than colonizing worlds beyond. Without a diaspora, the probability of discovery was narrow; Akashar and its trail of debris occupied less than a hair’s width on the cosmic map. Each pattern in the debris made way for another. Like layers of rock and deceased life-forms beneath ground indicate the life of a planet and its inhabitants, the stream of extraterrestrial waste indicated the civilizations of Akashar.

“History,” he concluded, “is physical. A timeline in space.”

“No shit,” Tito said behind him.

Burhan swiveled in his chair but chose to disregard the engineer’s remark.

“What I still cannot determine is how they passed,” Burhan wondered, rubbing his jaw.

Tito held his cigarette aside and pretended to blow smoke.

“How does this not to disturb your conscience?” Burhan demanded. “That we can watch the history of the extinction of a sentient race — likely the only other such race in existence — before our eyes?”

Tito tapped the smart glass built into the jinn’s thermodynamic cage.

“And these bastards?”

Burhan squinted. “Pardon me?”

“Jinn aren’t sentient?”

Burhan shrugged. “You’re the man who operates the tank.”

“You traveled in this ship.” Tito clutched a rung. “Kradys built the damned system anyway. ‘Economic progress.’ ‘Interstellar cattle.’” As Tito stepped close, Burhan could smell the man’s odor gravitate toward him. Tito stopped inches from his face. “Just because I take advantage of the bastards doesn’t mean I think their brains are mush. They’re the ones who found this place first.”

“No. The jinn from the Hydrogen Bridge—”

“Oh so some jinn are sentient?” He raised a wiry brow.

Burhan sighed. “I feel disinclined to comment. We know terrestrials spoke of them millennia ago. They lived, occasionally hidden, among us on Earth and existed long before our species evolved. We’ve enslaved them for so many millennia that, even if they did possess the faculties of man, they do not feel resolutely — hm, that word — alien.”

“If they’re not alien,” Tito replied, left nostril twitching, “then what the hell are they?”

Burhan raised his arms. “So after all that fuss, you suggest they are animals? Smart, gaseous monkeys? Savages from the hydrogen jungle or Earth or whichever planet you so choose? Is that the answer you’re looking for, my friend? Because I have none.”

Tito scoffed. “No, my friend,” he replied, imitating Burhan’s pitch. “I’m not suggesting they’re animals. I’m suggesting the opposite. You intellectuals, this idiot crew, this damned intergalactic culture of comatose fuckups —” He paused, staring into La Mariposa’s cragged ceiling. “You’re an archaeologist, not a philosopher, but you are obsessed with the Truth. Whatever that fucking is. Even you can’t figure judgment from fact. You’re no different from a bureaucrat. You think either too much or too little. You’re as stupid as your brother. He believes in dignity and rules. That makes for a bad revolutionary; he’s the one captain who didn’t die in the war. Fuck the rules. Your brother doesn’t care about discovery or tragedy. He cares about honor, as if that’s something else. You don’t know how to care. Who makes the rules for this shit? There’re no rules for mass extinction, man.”

Burhan thought for a moment that Tito was talking to the air. Was that foul-mouthed cretin mocking him?

“You defile my brother’s name,” Burhan murmured.

“Did you hear a fucking word I said, Jimenez?” Tito looked away and waved a hand. “Whatever.” He shrugged, looked back. “I just happen to think we’re all implicit in a system.”

“A system?”

“Yeah. No escaping it, not even death. Or shit.” Tito grinned. “Which is why, you know, who cares? Stick ’em in a fucking tank for all I care. End of the day, no matter what I do, I’m just another comatose fuckup like you, no matter how much I deny it. I know these space monkeys must be self-aware” — he tapped on the cage — “but the idea is so socially, biologically, existentially… wrong. It can’t be!” He threw up his arms. “Impossible! You know? You know. You know exactly. We’re brought up like that. It’s in our blood. That’s self-awareness. But unlike you, my friend, I thrive in the Hell of civilization. I embrace evil. You languish in its banality, searching desperately for a way to be anything other than a product of our time.”

Burhan scowled. Tito was out of his mind. He couched himself in proletarian straight talk, but beneath the veneer he was a misanthrope. One does not argue with madmen.

Tito laughed at him and inserted his cigarette between his lips.

The intercom blared. Burhan cocked his head. He watched Tito extract his cigarette. In the backdrop, the jinn scurried in their tank, a contained storm of crackling blue fire. The com buzzed a second time. It was Najam.

“Cortes here. The probe found something. I think…” Pause. “It’s a flag.”

The Inorganic Biologist

Karell Cory found it difficult to describe the condition of her fiancé, Paco Sol, without scientific precedent. The most she could say was that the alien shit was eating him from the inside.

Alien enzymes reversed his genetic structure constantly, molecules realigning, shifting to left-handedness in a chain reaction. They tried to recreate the foreign inorganic compounds in his system but couldn’t, not fully. So his genes crumbled, malformed helixes splitting slowly like cracked ice. There was a reason life as humans knew it was based mostly on right-handed DNA. The only thing keeping his system from falling apart was the garish blue glow of his cryogenic cocoon. Even that wouldn’t last. It was partly to blame.

Karell touched the surface and shivered. Beneath the icy saline goo, Paco’s pale complexion radiated white light as if he were a pile of bones at the bottom of a pool. Paco had lived decades in cryo as he delivered corporate goods across void, in ricochet between Bashar and Gliese 581g, and then one day he’d found the black orb outside the wastes from Akashar.

“Idiot,” she told the cocoon. “Why’d you touch it, Paco?”

The cocoon growled.

“You’re not a fool, are you?” She smiled briefly.

Paco had killed dozens in attempts to find a cure, but he wasn’t always a bad guy. His problem, Karell believed, was that he hadn’t considered death since the war. Death scared him. None of this was his fault. He’d say it was God’s, she knew.

Paco was always scrawny. He had a hard life trekking in cryo between Bashar and Gliese 581g. He had learned to deal with it even as he searched constantly for a way to settle down. He rode in Paradigm, the smallest ship in the corporate fleet, and had the sense of humor to think of this as a joke. He had a pet Empress, a charaxes brutus natalensis whose wings and abdomen were brick-red splotched with white, the tips of her wings lined with those colors like a mutated peacock’s spread. He named her Esperanza. He didn’t feed her too much or too little and built a tiny cryogenic cocoon so she, like Paco, could last the years between the stars. After he and everyone else on La Mariposa except Orlando Rodriguez fought in the war, he hadn’t hurt more than a fly.

In those days, before the last fleet of Kradys ships arrived like cities in the sky, he was a war hero. After the last rebel ship plummeted into the sea and Kradys settled on Dominico’s beaches, just before the corporation ordered Paco into his menial career as interstellar delivery boy — as he lingered through that no man’s land of memory, forgetting the fighter he was and meandering through memories of the present, the military compounds on the beach — he had met Karell. She had graduated from the academy that year. The two of them spent weeks on the damaged beaches sunbathing between the wrecks of fallen ships.

Within the year they were engaged, but soon Kradys contracted Paco to his reparations job as interstellar mailman. The couple vowed they’d find the cash to settle. She stuck it out in cryo on Dominico, waking up for two weeks every few hundred years. She worked her biologist’s grind from the plug-in during sleeps, running equations, formulae, and diagrams. They were bizarre creatures in her icy, electric dreams. Dreaming in cryo was proprietary technology. It scrambled her brain every time she popped out. Insomnia, migraines, cycles of melancholy and rage.

Karell sent him messages when she woke. He sent messages back. As the years passed he stopped replying. She figured he’d given up on their prospects. She would have too if she hadn’t holed herself into the long-term cryo job.

From what he did send Karell, it seemed he had become a reader. When he wasn’t in cryo there wasn’t much else to do. He would float in the middle of his ship’s cramped bridge, the Empress fluttering on his shoulder, and call books out of the display. Sometimes he would read them, sometimes he would turn on the audio, close his eyes, and listen. At first they were novels — adventures and romances, as if to replace what he had lost, his memory of Dominico now reduced to an aspiration.

When he ran out of novels he read philosophy, religion, science, politics, whatever else he had in the database. He disagreed with a lot of it, he wrote to Karell. He agreed with some of it. He figured it didn’t really matter what he knew. He described himself as an observer dislocated from space and time, studying the distant intellectual produce of his species from afar.

“Not out-of-body,” he wrote to her. “An out-of-civilization experience. You ever had one of those?”

This was the closest he usually got to human contact.

Paco was a delivery boy after all. What did his dreams matter? What did any of theirs?

Of course, what he read was what Kradys had on file. And what it had on file was a few millennia old. Anything Dominican, anything without a link to Kradys or the Medusa System, was absent. There was no way Paco could ever know what he didn’t know. Karell tried to explain this to him, what she knew from the journals at home, the attempts to rewrite history, but even she struggled to deny her own presumptions. In the end, she wasn’t reading history written only by the winners; it was written by the losers too. Dominico’s Golden Age still concluded with her people’s failure to uphold the planet’s economy, culture, and military might, no matter how Karell tried to explain it away.

She suspected this interpretation was wrong — wanted it to be so — but like Paco she also suspected, when presented with meager information outside the Kradys archives, that she hardly knew how to reconstruct a different narrative. Their people’s history had been taken from them. They did not know what they didn’t know. There was only the conviction, the faith, that they could not — should not — be blamed for their own demise.

Conviction wasn’t enough for Paco. He could not take solace in who he was. There was nothing to take pride in. They’d lost the war. That much was clear. In place of pride, Paco felt what Karell could only interpret as a religious combination of fear and awe of the corporate empire. Kradys thrived on the idea that humanity was the only thinking species in existence. People were destined to conquer the stars, the stars being their domain alone. Top of the food chain. Kradys had delivered this message to Paco, to humanity, and thus deserved to lead this uncompromising conquest of the infertile universe. They had unveiled their species’ purpose through the power of rational inquiry made possible by technological might, and so they possessed the right to govern it.

Surrounded by outer space, Paco wrote to her that he could not bear to look into the cosmos, as if its expanse were as looming as a Kradys compound on a Dominican beach. As if it could crush him with its emptiness.

Then, a century later, Paco found the stream of debris like a river from Hell. The thing from Akashar.

Everything made sense to Karell. Like ice XI, Champollion’s Foot transformed its host following a process of freezing and electric shock — which was exactly what happened in cryo. The process triggered the necessary enzymes, a biological switch.

It made even more sense for Akashar. How does life come out of a planemo, wandering in the cold, dark space between suns? How did life happen without a Goldilocks zone? The answer was obvious now. Akasahar didn’t need a star. It sat in a patchwork of dark matter. A cosmic womb. The stuff drifted everywhere near the center of the Milky Way. When dark matter came into contact with itself, it generated heat. Pocketed in the core of Akashar, dark matter collisions produced the thermal conditions necessary for an inorganic, DNA-like structure like Champollion’s Foot to evolve. These were also the perfect conditions with which to develop molecular chain reactions similar to that of ice XI.

Karell didn’t know what to say. For the first time in her life, she felt no desire except the need to know why. Why would God do this to the crew, to Paco, to Akashar, to the human species? She couldn’t ignore the existential questions.

But it wasn’t God alone. The flag Cortes found was dark blue behind black ships. The Kradys logo. If this was an act of God, God worked with human hands.

Karell heard the door unlatch. The sound echoed through the chamber as she turned. In the artificial breeze, the Shaykha’s robes billowed around her colossal figure.

“The cryo will hold him but not for long,” Karell said. She touched her thin-rimmed spectacles. “I’m sorry.”

“As am I.” The Shaykha smiled. “You would have made a fine daughter-in-law, once we overcame our differences.” Karell thought she detected scorn. The Shaykha placed a wide palm against the cocoon’s surface. “There is only so much we can do,” she continued. “I suggest we let him pass naturally.”

“That would hurt him,” Karell said, shocked.

The Shaykha nodded as if unaware of Karell’s bitter reply. “At least he will leave this world conscious.”

“Even if pain is part of it?”

The Shaykha moved a hand over the cocoon’s dashboard.

“I think my son would want to know about the Akasharians and his impending death. When death arrives, we should feel our last breath. So we understand we cannot live if we do not also pass from this world.”

The Shaykha wasn’t usually this masochistic. Karell watched her type commands into the dashboard.

“Did you hear the news?” the Shaykha continued with brevity undeserved for knowledge so devastating.

“The flag?”

“Yes.” She paused to inspect Karell with amber eyes. Paco’s eyes. “You don’t seem surprised.”

The news of xenocide had occupied the silent quarters of La Mariposa since Cortes radioed in thirty minutes ago. Karell had greeted Cortes when he returned to the ship and had helped him depressurize his unwieldy suit. He was surprisingly wordless for the hulk of a man she knew. There was no talk about following orders or important memories of lessons learned. He only stared at her from beneath the dark visor, air hissing through the constructed perforations in his suit, breathing heavily. His black-flecked, grey pupils were hard as chiseled granite, daring Karell to stain her cheeks with tears. She wasn’t that kind of girl.

“I think it makes sense,” Karell replied to the Shaykha. “Violence is natural to us. It’s natural to the Akasharians. It’s written in their DNA for God’s sake.”

“Champollion’s Foot,” the Shaykha suggested. “Chain reactions. Biological switch. Enzymes. Converted genes.”

“Yeah, biological colonization. Life comes at a price. I don’t think it’s right, but it’s evolution.”

The Shaykha had returned to the dashboard, but she looked up once more.

“With due respect, my dear, that’s bullshit.”

Karell put a hand to her mouth. She’d never heard the Shaykha this crude.

The Shaykha pressed a button and the cocoon shook, then cracked open. Goo began to seep from the edges. Beneath, the body began to twitch.

The Delivery Boy

Paco Sol woke with a shock. He felt the cocoon’s defibrillator lift off his chest as he rose blind through the icy saline goo. No one dreamed in cryo. Time passed, dark and empty — and then, with this shock, the undreamt nightmares of a decade under and light-years of travel coursed through his consciousness.

His mind’s eye filled with the grey skies of Dominico. The long, dreamless hauls between Bashar and Gliese 581g. The stony gaze of Gliese 581g itself, the Capitol.

In the dark beneath his lids, he saw the giant eyeball of Gliese 581g below, fixed in synchronous orbit so that its dilated, dark blue pupil gazed forever into Medusa’s dying glare as if intending to go blind. One side of Gliese 581g always faced the sun, warm enough for an ocean, albeit lifeless. The other side, like a grey cornea, always faced the cold of space, a dark sheath of rock and ice. Below, Medusa’s steady glow carved the distant cities into dark silhouettes bobbing in the water. Slabs of thin ice shifted like tectonic plates on the surface of a cool, violent magma. Medusa’s red light spread everywhere.

Paco had seen this before. He’d seen it too many times. For years he had traveled in cryogenic suspension between Bashar and Gliese 581g, staring inevitably into Medusa’s nightmare of fire. He had learned to muster the eerie sight, admire it occasionally, and appreciate the solitude of interstellar travel, even as he searched for a way to return permanently to Dominico. Usually he couldn’t bear the sight of outer space. He had seen too much of it. But Gliese 581g — now in his mind’s eye a dark spot against Medusa’s crimson disc — drew emotions from him. He felt like a child confronted by a ciguapa, paralyzed by deference and terror.

Now his eternal ricochet between the stars measured itself according to the time he would last until his DNA crumbled like old brick.

When he recalled his condition and felt the fever and the tension in his stomach, his eyes burst open. The light of the ship’s cabin filled his retinas with bright white, dispersing the mental image of Medusa and the Capitol. He glimpsed the sepia blur of his mother’s robes. The thawing goo needled through each pore in his skin, cold and sharp, reminding him of the first time he had taken it upon himself to handle the alien thing he had retrieved from the sinew of waste. The acute chill of the object from Akashar lingered in his sensory memory.

He gasped as he pushed from the cocoon. His pale, hairless body tightened, stretching across his bones. He winced as his mother placed her coarse palm against his back. For several minutes they maintained this position. He breathed deeply from La Mariposa’s filtered atmosphere.

“How long?” he croaked.

“One thousand one hundred and forty-three years,” someone said. His mother’s voice? Karell’s? His ears were clean of goo but numb. Speech came to him as if through water. “Average time for a trek this distance, don’t ya think?” the voice concluded. It was Karell, from his left.

He focused on the blur in front of him, where he distinguished a yellow headscarf. His mother. She hadn’t woken him with a cure, her silence told him. Why had she woken him, for her pious bullshit?

“They killed them,” Karell said, seeming to blurt the words. “The Akasharians are dead. Akashar is ashes, Paco.”

“Who?” He blinked hard, feeling his sinuses widen. “Who killed them?’

“Kradys,” she replied.

He focused away from his mother’s blur.

“Fuck me,” he declared, then shrugged. “Not unexpected.”

“It’s unexpected for me,” his mother said finally, her voice deep and smooth.

“It wasn’t a question, Mother.”

A time passed. His mother didn’t say another word. Was she afraid to speak to him, embarrassed that she believed in God in the wake of the day’s revelation?

A thought occurred to him. He wondered why he had never asked before. Then again, there hadn’t been much of a before for him and his mother.

“Mother,” he said. “You pray five times a day?”

“I adjust the math for travel, but yes,” she answered.

As she hauled him the rest of the way out of the goo, her fingers bit into his skin. She had detected his mockery of her antiquated rituals and chosen to ignore it. She wanted to derive meaning from his final hour, to bond with her last and only son.

He refused to spare her the courtesy.

“We were under for a thousand years,” he said, continuing his game. “That mean you don’t pray in cryo?”

He heard her laugh. “There is some disagreement among scholars, but most would say, when we study the science, that cryo does not count. Take life in moderation and according to circumstances. It’s a stasis anyhow.”

“So to you it’s like dying.”

His pupils adjusted so that he could now identify another figure behind his mother. Karell. Whatever life he could have lived with her was gone. She was looking away, arms folded behind her back.

“I suppose,” his mother agreed. She handed him his clothes. “For the purposes of jurisprudence, yes. In suspension you may as well be dead.”

Paco grunted and found himself remarkably sincere. “Sounds like a damn good definition to me.”

Kradys had robbed him of his aspirations, quietly and by force, the way a cryogenic cocoon’s blue glow, soft but insistent as an unblinking neon sign, deprives its user of dreams. Indentured servitude to be a fucking delivery boy. Part of the corporate machine like jinn in a thermodynamic cage. What’s sleep, the jinn liked to say, without dreams?

The Shaykha

In this moment of revelation, Shaykha Suraya Shatir could only fear. Now that the crew understood the cause and gravity of Akashar’s demise, now that she had already radioed out the existence of Akashar, Kradys would track their location if the crew didn’t leave within the hour. She hadn’t forgotten the technological feats of their enemy during the war: signals intercepted by ansible technology inaccessible outside the offices of power, Dominican fleets underhanded by machinery indescribably of human origin. Most of all, she feared for her son.

Paco had taken the news well. Nothing could break him further. He was no longer hysteric.

He slid off of the cocoon and landed on his feet. Unobstructed by the cocoon’s light, the grey-blue hue of La Mariposa accentuated Paco’s pale, gaunt features. He stooped the way a spider bends over itself in rigor mortis, its mind refusing to acknowledge its mortality while its body yearns to accept what it has coming.

“I’m dying,” he managed, as if realizing it for the first time.

“Ina’lilahi wa ina’Illaihi raj’un,” Suraya crooned. She touched his shoulder. “To God do we belong and to God shall we return.”

“I’m not returning anywhere. I’m going to die.”

She slipped off her glasses and rubbed the loose, dark skin around her eyes. “There’s beauty in death.”

His features hardened. Skin stretched across the ridges of his brow. His apricot eyes glazed over. “No. There isn’t.”

Paco turned and ambled into a corridor as queasily lit as his own complexion, a skin color that suggested too many years in cryo between the stars and too few awake on the worlds that circled them.

Karell glared at Suraya before following him out. Suraya frowned. It had been so many years since she had spent time with her son. Kradys had stuck him in that job for a decade. It was by sheer luck that her travels coincided with his, that they were still alive to see one another, even if for the last time. Thank God for relativity and cryogenic science.

Suraya extracted a string of rosaries from her pocket. She considered consoling Paco. She knew he didn’t want to talk with her. He saw her faith as a crutch.

As she whispered the Ninety-Nine Names of God, she remembered her little sister’s funeral. Her sister was twenty-two. Suraya had received a message from her mother. She recalled running through the hospital with her father. Through familiar corridors. Up the elevator. Across the waiting area. A sofa. Two thick pillars.

“Is she all right? Is she all right?”

Dry silence. Her uncle leaning against the door frame, head shifting left, right. Sobs from the hospital bay, seeping between the throbbing in her ears, as if they’d only now risen to an audible cacophony.

The door frame grew. Cold flesh on the white, white bed. Ringing.

“It’s been ten minutes. Where have you been?”

Memories of long days on the Dominican beaches crashed against the bank of her consciousness until, finally, they flowed as tears. She felt detached, pathetic, sitting cross-legged on the floor with her head down and her knuckles pale, leaning against her grandmother’s knees.

As per tradition, family would wash her body within a day before sending her Earthward for a proper burial. They kept her sister at a funeral home during the night. The next morning, Suraya, her mother, two aunts, and two cousins left for the funeral home. They cleansed her sister’s cold form. Blood flowed from the tiny incisions where doctors had applied their needles; no life system remained to clot the vessels. The blood looked bright and fake, and the scene seemed to pass without end. The process was thorough, cathartic. Suraya remembered trying not to cry. The soul has a harder time leaving when people can’t let go. It has to be able to let go. She had to be able to let go.

At the burial, they lowered her sister’s body, wrapped in white cloth, into an old and yellow cryogenic chamber. The closest of kin — Suraya, her parents, and her grandparents — knelt to the chamber and lifted. They hauled it to the tiny rocket nearby, no taller than a tree, and slid her sister’s chamber into the inner cavity. Her grandmother shut the door, locked it, and keyed Earth’s coordinates onto a remote panel. They prayed. One by one each willing relative passed the rocket and looked upon her sister’s shape, wrapped in white beneath the yellow goo as if caught in the process of metamorphosis. Her grandmother pulled a lever and the small crowd slowly departed as the rocket hummed to life. They were a kilometer away when it torpedoed into the sky, trailing a bright yellow plume. Distant relatives would receive her in Earth orbit and bury her covered with that bare white cloth in a spot overlooking the Caribbean. No caskets. No tombstones. No gaudery.

We come from dust, we return to it. Ina’lilahi wa ina’Illaihi raj’un.

In La Mariposa, Suraya thumbed her rosaries, head inclined and eyelids half-cast, and listened to the ship’s incessant groan. She relived memories of her sister, reminding herself of what it first felt like to lose a loved one, as if in preparation for Paco’s death. It was difficult to love a man she scarcely knew.

Behind her, she heard crackling fire.

Suraya flinched. She dropped her rosaries and turned toward a bony, wrinkled face shrouded in pale blue mist. The jinn had drifted in through the wall, his cloudy shape diffusing in the pressurized cabin of the ship. He grinned, a form like gnarled roots in his mangle of blue flame. It was Istikar, Prince of the Hydrogen Bridge.

“Salaam, Istikar,” she mouthed bitterly, bracing her muscles, before he dove beneath her arms and snaked round to her back.

She could feel the heat of him over her left shoulder. Whispering. Something unintelligible, an accumulation of neural triggers, emotional catcalls, demanding actions out of her involuntary biology like a magician conjuring spells from rock. Searching her brain like a database, invoking the collection of words and emotions he agreed with, even if she had buried them. These thoughts gathered in her ear and ran down her spine, prickling every nerve in her body. She could parse out meaning, interpreted through the networks the jinn activated inside her body —

Before Paco woke…

She felt a rush of heat, a sharp, familiar gas on her tongue, and gagged. Her whole body convulsed, arcing like she was about to retch. Suraya’s mouth opened against her will, finishing the sentence aloud —

“… you spent more time with a suspended corpse than with the living,” the jinn mused, through her.

Istikar was a free jinn, from the swathes of gaseous refuse between galaxies. Deuterium. Lambent blue fire. Suraya was among the few who still called them free in the true sense of the word. For most, free meant wild, like untamed steeds in untouched land, although Kradys had by now begun projects in the Hydrogen Bridge. Unlike their enslaved cousins terrestrial to Earth, the free jinn were not discovered until humanity left the solar system. It was hardly a discovery, given that jinn were by that time a known species. A known commodity.

Suraya ignored Istikar, concentrated her mind on nothing, and forced out the thoughts the jinn had summoned from deep inside her mind as a means of communicating on his own behalf. The heat receded to her stomach, away from her spine. She found herself unhinged from Istikar’s neural anchor.

“Why didn’t you tell us about Kradys from the start?” she demanded. “You could have spared us many hardships.”

She was used to this, the temporary possessions. The invasions of privacy. That was what jinn did. Possession was the only way to communicate with them. They had to creep in and access particular fundamentals of human biology, the building blocks of temptation translated into puppetry. No wonder the Devil was a jinn. No wonder no one thought of jinn as sentient: they communicated exclusively through human bodies, and what they could communicate simply rehashed latent thoughts and suppressed desires. For this reason people hardly interacted with them at all. Suraya had relayed Istikar’s message about the Akasharian extinction to the crew, and it was only by her authority, she knew, that they implicitly trusted what Istikar had to say. It required enormous composure to communicate with Istikar’s kind. A state of controlled entropy. A tolerance for pain and ideological dislocation.

Others called it induced schizophrenia.

Istikar’s blue eyes appeared before her, glowing, and then plunged into her breast. She lurched again, gasped, felt him dredge through her mental backlog until words emerged from her lips. She spoke to the empty cabin —

“You in all your honor and integrity, you whose moral gravity draws the respect of the defeated souls aboard this ship with such weight that they will sleep in the cold to the end of this universe for you, to save your son… Even for you, to be told of an extinction at the hands of your kind… You…” She coughed, resisting. “… Not — would not — believe. Even if Kradys, predictably, perpetrated this crime. Neither would your… crew… no matter what they claim after the — fact.”

She grunted, then quieted. She waited for him to continue. A portion of his flame burst out of her, drifting before her, churning the filtered air —

“I was eavesdropping on your conversation with the girlfriend.”

Furrowing her brow, pushing out the being of smokeless fire, coughing —

“She’s a biologist,” she corrected. “Of sorts.”

Again, Istikar plunged thick rivers of lambent blue into her body —

“Inorganic biology.” The blue haze before her laughed, a noise like crackling fire. “I think her… bitter. She blames God. Paco also does — similarly.”

Suraya grimaced. Outrush of blue —

“What do you want, Istikar?”

And back in, hot —

“You know what I…want, Shatir. I — I… relish your torment…” The haze moved closer. “So,” he said, through her, a wheezing, guttural sound. “Do you blame God? Why does suffering exist? Where are the answers in this mess?” He was prodding her limits.

Suraya exerted him outward, straightened her glasses. She bent to snatch her rosaries, pocketing them, and then stood, facing the blue flame but thinking inward to the part of the jinn still there. How unsettling, and yet how appropriate, that in order to speak to an Other she in fact spoke to herself.

“Faith is not a source of knowledge as much as it gives us a means of understanding it,” she replied. “Answers are, in a way, irrelevant. Our enemy is not God. We cannot presume to know what is beyond our comprehension. Our enemy is ourselves.”

She jerked —

“So you believe in free will.”

Her last push against entropy, expelling the jinn like vomit —

“Of course.”

Istikar swept out of her in one final rush. Once again, the crackle of laughter burst from the lambent blue silhouette.

The Jinn

None of this was revelatory to Istikar. He didn’t have any thoughts on the issue. He had only memories.

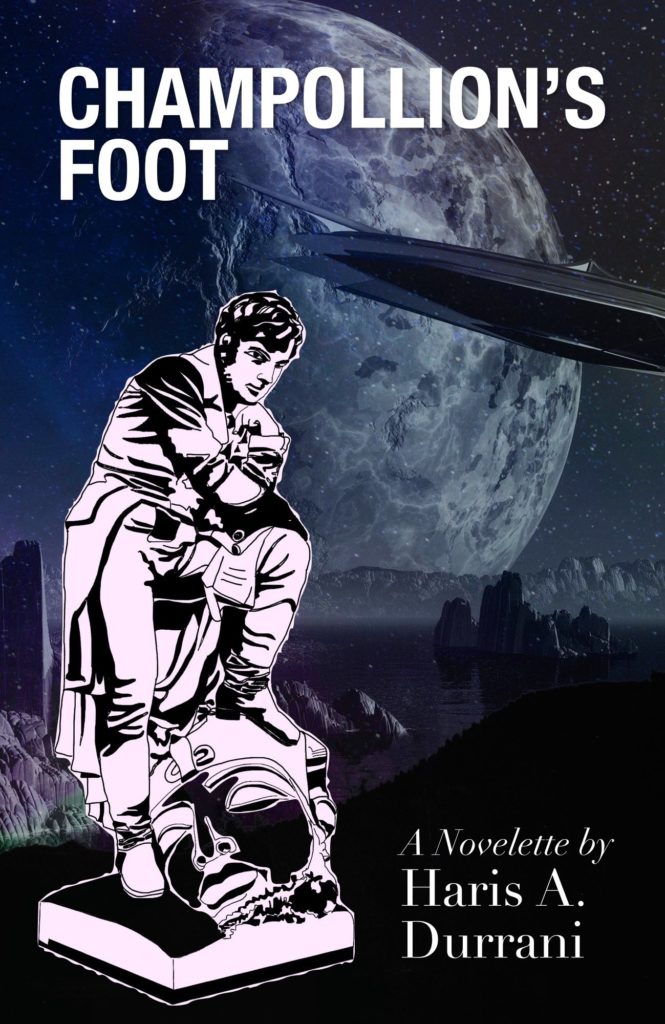

He had lived long enough to remember the era of Jean-Francois Champollion himself. Champollion’s discovery of the Rosetta Stone had enabled communication with a culture not only distant in space but also time. His contribution to the study of ancient civilizations, particularly Ancient Egypt, was tremendous. And yet this very study also resulted in the erasure of a millennium of another culture’s history from the world’s historical consciousness.

For one thousand years preceding Champollion’s era back to antiquity, a civilization had thrived in Egypt, one which birthed many of the greatest artists and thinkers in history. They had ruminated on inertia, momentum, the camera obscura, and optics. They had preserved and improved upon Greek and Roman thought, science, and art. They had written poetry that could make sisters and brothers of enemies; that could excite the nerves of gentle old men; and that could melt even jaded jinn such as Istikar, though he didn’t like to think of himself as such then. Egyptology contributed to a view of history that diverted focus toward the present and the ancient and away from the interim. It stuck a hole in the course of time, like the man-made gap in Earth’s polluted ozone or the artificial one wrenched out of Akashar’s littered sky. But this was not to glimpse the beauty of worlds beyond grasp; rather, intentionally or otherwise, it was to conceal them.

Nothing of significance had occurred, the implication had it, for one thousand years. People like Champollion had entered, robbed what artifacts they deemed fit, and restructured the history to an effect that implied that the civilization living in this period had contributed little to the progress of human history. These were the dark ages.

Soon, prestigious academies in Earth’s western hemisphere established reputed Chairs of Egyptology. In France, before the Sorbonne, Champollion’s statue stood tall, one boot atop the crumbling face of a pharaoh’s bust. The millennium that had birthed some of history’s greatest works of philosophy, art, and science was forgotten, even by the progeny of that civilization itself. Pyramids, pharaohs, and Moses now occupied the cultural consciousness above the poetry, philosophy, and science of medieval Egypt’s thousand-year heyday. The latter had devolved into an outlier in the course of time.

This was a system based on forgetting. Champollion was not the instigator, but he certainly enabled an historical pattern that continued for millennia. Neither was Egypt the locus of the problem. But it was certainly a symptom. The devastation of that moment still burned in Istikar’s memory.

Today, the modern era had yet to pass. It moved like a slow death, always in anticipation of apocalypse by its own hand, as if possessed by a Napoleonic inferiority complex. It teetered on its inflexible call for progress, as if willingly chained to the idea that it had reached the end of history. Under the guise of modern philosophy, politics had infested everything. Peoples were erased, genocide and colonization justified under modern civilization’s new way with power. God was political. Morality was political. Science was political. Even death was political. And politics was the reserve of bureaucrats and their labyrinthine offices. Whether one believed in life after death or not, only its completion relieved the living from the constraints of the modern condition. No posthuman race had emerged, no singularity, nothing with which humans might transcend their bonds.

This was why, when Shatir told Istikar she believed in free will, he laughed.

“Age has granted you knowledge,” she murmured in reply, “but not wisdom.”

He plunged into her, searched her synapses for those unprocessed thoughts he needed, picking them out and regurgitating them through her own throat —

“Why don’t we count? Would the Akasharians, if they lived?” he forced out of her. “Why do your kind hesitate — upon the idea of our consciousness?” These were her thoughts, her fears, ones she hid or disbelieved, but with which he agreed. “I will… tell you. In the beginning — God created the universe… the Heavens, Earth… the angels, who obey God’s command. God created jinn from smokeless fire, capable of commanding our own fate, but our civilization wasted its existential nuptials with war. So God created humankind from Earth, likewise unstuck from determinism, and called all Creation to bow in respect to Adam and Eve. But one jinn, Iblis, the Devil — he… did not. He did not recognize your kind, Shatir, as conscious. Not elevated. Not hot and light as smokeless fire. Incapable of resisting basic temptation, of thinking for yourselves, of overcoming involuntary biology.”

She began to spasm, losing control as his temperature rose, but he would not relent.

“Today we find a… reversal. You… dear Shatir… your kind is now Iblis. Like him, you refuse to bow in respect of the equal ground of another like yourselves. Like him, you are possessed by your deluded sense of enlightenment. But you are only enlightened — conquered — by those among you who bear arms… shed blood… eradicate dreams. Kradys. According to scripture, our two species are not meant to interact. Once, many millennia ago, we did so among a few. But — now. Now…. Perhaps God does not wish for us to communicate with other intelligences, as few as there are. I believe we would… destroy them… as we destroy ourselves. We see in each other only… animals. Constructs of evolution.”

She forced him out, slowly but with strength, and moved so close he singed the hem of her scarf.

“I’d like to believe otherwise,” she said. She rested her palms against her knees, catching her breath, her towering figure reduced to fits.

Observing this, Istikar felt, for a brief moment, grief. He had not experienced this for many millennia, such a deep feeling of sorrow.

“You forget one thing, Istikar,” she went on. “The Devil is not divine. He challenges God, says he will cast humanity astray and thus prove our inferiority. God humors him. God lets him wreak trial and tribulation upon humankind, knowing, in the end, that we will not fall prey to the Devil’s tricks. The Devil is powerless. Is that too hard for you to believe?”

“If there is one thing I believe,” Istikar replied, diving back in, feeling her resist like a clenched fist, “it’s this: The human race can go to Hell.”

And yet the sorrow lingered. He could sense in her the feeling of anticipation, unspoken intentions whispering from deep in her organic circuitry of clay.

Why did God command Creation to bow to Adam and Eve? she was asking herself. Because they possessed the highest form of knowledge. Understanding. Consciousness. Angels follow God’s orders but have never possessed true understanding, were never sentient. In the beginning, jinn possessed this form of knowledge but squandered it; consciousness without conscience is not consciousness at all.

Istikar understood her conviction now. She planned to broadcast the flag, to make people see, to show them Kradys was wrong, so wrong that the corporation had worked — massacred — to sustain its lie. To give them ashes from which to rise. She would display an article of knowledge so terrible no amount of indoctrination or apathy could trick their conscience. She believed resolutely that conscience existed; beyond the facades of politics and culture there was a moral bedrock from which all beings could draw, each in their own way and by their own time and place.

What is the panacea of this endless modernity? How does one defeat a system based on forgetting? The thought — hers, his, he found them difficult to distinguish as his blue flame settled like an aura around her sepia robes — pressed into him with patient ferocity. The answer poised on her tongue, on his fluid kinematics, on the premonition of a thought of a whisper — By the recollection of knowledge presumed unknown.

The Akasharian

In death, each Akasharian experienced its own moment of revelation. Most would recall, looking back, that in order to live one must die. The purpose of life was not to consume but to recycle.

Akasharians wouldn’t call it Champollion’s Foot. They believed it was adoption, not destruction. With every new form of life that their enzymes converted, both the new and the old lost something, while each gained from the other. Their corpus adopted new forms of life, again and again. There were costs. There were deaths. There was growth.

As the Akasharians would say, colonialism was not timeless. It wasn’t human. It wasn’t jinni. It wasn’t Akasharian. It had little to do with evolution. Like life itself, it was only temporary.

For the empire would now know the cause of Akashar’s fate. If Paco Sol lived for anything, the Akasharians would believe, it was this. If he died for anything, it was this. The xenocide transmission, as future generations would call it, was Paco Sol’s legacy, and his mother its agent. Like Galileo wielding the evidence before his inquisitors, Shaykha Suraya Shatir would radio out a second message to the empire: the image of a dark blue flag squirming in the near vacuum of the desolate landscape of Akashar, the world without light.