Geopolitical flashpoints are not always unusual spaces of stunning, ethereal beauty. The state of Jammu and Kashmir is an exception: a strategic flashpoint etched on unsuspecting travelers’ minds as “a heaven on Earth,” the Kashmir Valley is a seismic zone of extremely high machtpolitik-al activity. Kashmir has been a bone of contention not only between India and Pakistan but also, due to a de facto and de jure Sino-Pak alliance, between India and China.

The roots of this bitterness could be traced to 1947, when ‘Hindustan’ of yore was cleaved into a secular India and an Islamic Pakistan. Hari Singh – the Maharaja of Kashmir – signed an instrument of accession with India. Pakistan, furious at being denied a Muslim-majority province, upped the ante – both politically and militarily – and invaded Kashmir using frontier tribesmen. This was more than six decades ago.

The unrest in the border state still persists. Low intensity conflicts and cross-border proxy battles still mar the zone – a cold war still defiles peace. India and Pakistan have, till today, fought three wars: 1947-48, 1965 and 1971; the latest in a series of national armed encounters was Kargil 1999. With such a loaded history, Kashmir doesn’t just emerge as another state for popular imagination on the subcontinent. It becomes a touchstone for India’s pluralistic identity and its territorial sovereignty. Simultaneously, Pakistan’s desire to ‘liberate’ Kashmir mobilizes people across the border in a similar manner.

Science Fiction (SF) – perceived by Darko Suvin as a “specifically roundabout way of commenting on the author’s collective context” (pg 84) – is extremely rooted in the times of its production and consumption. Indian writers, especially those writing a form of military-SF, may find Kashmir to be an ideal entry point into the discourse of post-colonial militaristic reassertion, ideological-based expansionism, popular politics and common imagination.

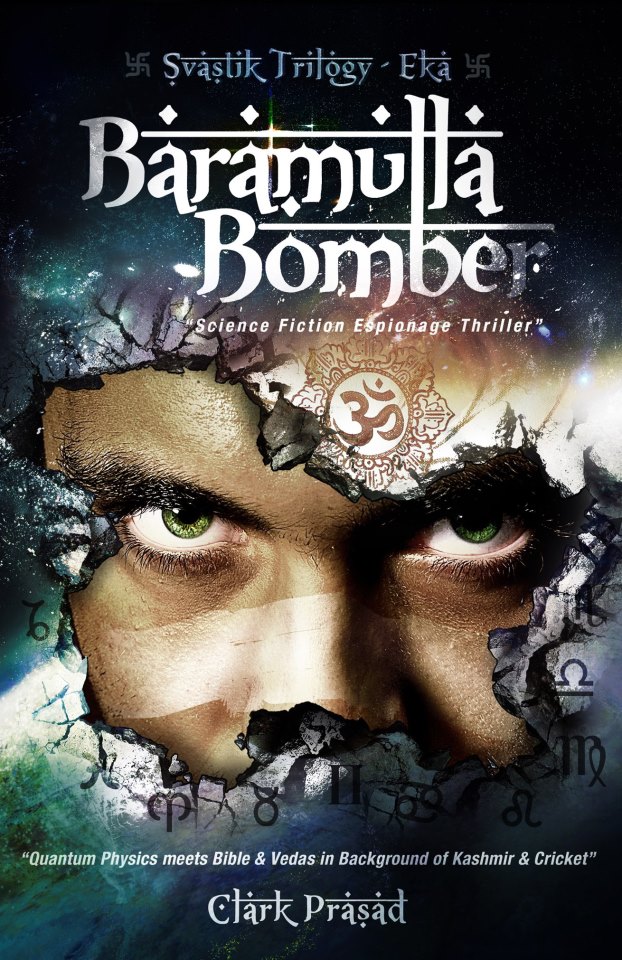

Clark Prasad’s 2013 novel Baramulla Bomber foregrounds, among other things, India’s vision of the religious and political ‘other.’ It features a renegade Chinese general uniting with the Pakistani military establishment in what seems like an attempt to further the dreams of a quasi-communist Caliphate. While the politics behind the operationalization of such a political entity – centered around Kashmir – is worth delving into, the ‘how’ of it – quantum mechanics meets mythology – is as interesting. The novel takes science (quantum physics, to be precise), seamlessly fuses it with mythology, and then spins a yarn of such mythological-military SF that it becomes, above all, a way to comment on current socio-political paradigms, especially in how it represents the religious and political other.

Clark Prasad’s 2013 novel Baramulla Bomber foregrounds, among other things, India’s vision of the religious and political ‘other.’ It features a renegade Chinese general uniting with the Pakistani military establishment in what seems like an attempt to further the dreams of a quasi-communist Caliphate. While the politics behind the operationalization of such a political entity – centered around Kashmir – is worth delving into, the ‘how’ of it – quantum mechanics meets mythology – is as interesting. The novel takes science (quantum physics, to be precise), seamlessly fuses it with mythology, and then spins a yarn of such mythological-military SF that it becomes, above all, a way to comment on current socio-political paradigms, especially in how it represents the religious and political other.

In Baramulla Bomber, Dr. Nasir Raja, a disgruntled Kashmiri separatist, creates a sonic weapon, one which derives its legitimacy from ancient scriptures and the universe’s primordial sound “A-U-M”. He is helped by Chinese generals and this rogue Jihadist-Maoist nexus plans to deploy this sonic weapon at a UN meet in Oslo. By locating global terrorism – centered around Kashmir as the leitmotif of the text, and the subsequent ‘scientification’ of mythology (as evident in the creation of this Biblical-Vedic sonic-weapon) – when set within the rubric of Islamic Republic of Pakistan colluding with the People’s Republic of China, the novel expresses a tendency to see Islamism and Maoism in the light of the ‘other’, especially from the perspective of an India of today. For the Indian popular imagination, after all, China is an expansionist Maoist power that does not recognize India’s territorial sovereignty in the north east (Arunachal Pradesh, for example), whereas Pakistan comes across as an Islamist state that does the same to India’s north (Kashmir, for example). Moreover, it is not only India which bears the brunt of this Jihadist-Maoist nexus, but the entire world, as represented by the planned sonic-attack on the UN. These implicit assumptions and scenarios are clearly established in how the plot evolves.

Baramulla Bomber begins with a massive earthquake hitting the Shaksgam Valley in Kashmir, and the world of espionage immediately begins to take note of shifting (political) fault lines. Intelligence organizations around the world focus their attention on South Asia. A foreign intelligence agent on the trail of finding more about this mysterious (un)natural calamity is assassinated. Spooks suspect that this earthquake might be the result of a Sino-Pak joint experimentation with weapons of mass destruction. Operatives weave through the tale, trying to find more information about the weapon, the terrorists, and where they will attack. The earthquake, as one later finds out, is a result of the sonic weapon, one which has been designed by Dr. Nasir with the help of China and Pakistan. The ultimate aim of the terrorists is to use this weapon during a UN concert in Oslo, thereby wreaking havoc on the assembled delegates. Since this is a sound-weapon, the terrorists believe it would be well-hidden – and would signify poetic (in)justice by deploying it during a musical ceremony celebrating peace. During the climax, an international team comprising Mansur, a cricketer from Kashmir, Aahana, along with the top-brass of India’s political and military executive foil this strike. Peace gets another chance.

Baramulla Bomber has an abstract – though eclectic – mythological backbone around which political flesh is woven, which makes it distinct. It utilizes the trope of a ‘golden past’ and a hyper-advanced Vedic civilization, from which the current India has devolved, not evolved. However, Prasad stays away from glorifying one particular religion as the fountainhead of all wisdom by including other religions in this gamut. This super-weapon might have been built by ancient knowledge of the Vedas but this know-how belongs to all of mankind and not just one religion. For example, this weapon has been described in the Bible, too.

Baramulla Bomber does not read as propaganda literature of and for the right since it differs from right wing manifestations of the narratives of golden past by attributing the source of knowledge to not only Hindu scriptures, but also to Abrahamic ones. Moreover, the international team that saves the day in this text is a syncretic mixture of nationalities and religions. Another interesting aspect of Baramulla Bomber in this regard is not the discovery of knowledge, but the rediscovery of it. This sonic-weapon is not a new invention: it is an ancient weapon that has been mentioned in the Vedas and the Bible. It was once sought by the Nazis and is powered by Brahmnada – the sound of the Universe.

For me, the novel is primarily a take on material realities. This weapon is first tested in the insurgency-infested Kashmir, on which both India and Pakistan stake a claim. In the age of global Jihadism, by locating terrorism centered around Kashmir, the writer is making an extremely tangible point that connects the world of the text with the world of the reader. Second, the revisionism of history using golden past and the subsequent scientification of mythology denote a majoritarian tendency to see Pakistan’s Islamism (and by extension, Jihadism) and China’s Maoism as the ‘other,’ especially from the Indian and American perspective(s).

It is not difficult to link such themes with contemporary India, one in which Islamist Fundamentalism and Maoist Extremism are increasingly being perceived as dangerous ideologies which seek to destabilize the Indian state. Swadesh Rana writes in “The Gravest Threat to India’s National Security” hosted on The Academic Council on United Nations System Information Memorandum 82 of 2010, (ACUNS website):

Home Minister Palaniappan Chidambaram has virtually tiptoed over a division between external and internal dangers in designating the Naxalites as the gravest threat to India’s national security. “They have declared a war on the Indian state,” he told a media conclave in Delhi on March 10. Comparing the Maoism-driven Naxal violence to the jihad-motivated Islamic militancy as the two biggest threats, he rated the former as the more serious. “Jihadi terrorism can be countered, usually successfully, if you are able to share information and act in real time,” said Chidambaram. “But Maoism is an even graver threat.”

While the former home minister, in a previous administration, was echoing what security experts had maintained for some time, Baramulla Bomber, by manifesting the other on similar lines, reconfirms the slow but steady assimilation of such a perspective by the Indian popular SpecFic writing – and reading – community.

Prasad, when asked if he was conscious of engaging in social criticism, replied (in a conversation on Facebook; 23rd August 2014): “Yes, Baramulla Bomber was shaped by immediate and forecasted future realities. The thought was how India and the world will shape up five years ahead, keeping the trilogy in mind. I was looking for solution to the Kashmir crisis, via this medium and start to find an answer on the origin of God. I thought of using sci-fi as genre as I believe scifilogists hold the secret of future of the world and the vision they see.”

This establishes a link between a writer of SF and his conscious efforts to respond to contemporary threats using the vehicle of SF. Clark’s novel is not merely an ‘escapist’ text: while SF – like Baramulla Bomber – might not lead to immediate, tangible changes, but at least it makes the reader aware of ideological confrontations and socio-political fault lines which exist around him or her. By formulating religious and political others, and by focussing on a fusion of science, mythology and ideology to prevent violence, Baramulla Bomber appears more concerned with peace than with war. By resolving a terror crisis through a cooperative global effort of the international community in an Indian military-mythology-SF thriller, the novel shows SF to be a mode existing in a plane above the petty boundaries of genres, ideologies, nations or people. SF becomes the literature of more than the ‘one.’

References

Prasad, Clark. Baramulla Bomber. New Delhi: Niyogi, 2013. [Goodreads]

Suvin, Darko. Metamorphoses of Science Fiction. Yale: YUP, 1979. [Goodreads]

Rana, Swadesh. “The Gravest Threat to India’s National Security,” The Academic Council on United Nations System Information Memorandum 82 of 2010.