If you sit alone at night by the sea, your heart will adjust to the rhythm of the surf. Give it a minute. Allow the chatter in your mind to cease. Listen to your breath follow the cadence of the waves. In the silence, you’ll get in touch with the best of yourself, your core values, and you’ll know the job we have to do. If nine billion of us are to survive in 2050, we are charged with six moral imperatives as ancient as they are urgent:

If you sit alone at night by the sea, your heart will adjust to the rhythm of the surf. Give it a minute. Allow the chatter in your mind to cease. Listen to your breath follow the cadence of the waves. In the silence, you’ll get in touch with the best of yourself, your core values, and you’ll know the job we have to do. If nine billion of us are to survive in 2050, we are charged with six moral imperatives as ancient as they are urgent:

feed the hungry,

enrich the poor,

cure the sick,

restore the environment,

power civilization sustainably, and

live in peace.

In this book you are going to meet six aquapreneurs who plan to fulfill these moral imperatives by working to build floating nations on the sea. They are launching their ambitions from four continents, and they are radically misunderstood by landlubbers. Several of them have independently cited 2050 as a deadly deadline, an approaching pinch point in the supply of several key commodities that humanity needs to survive.

Water: According to Growing Blue, a gigantic consolidation of data from industry analysts, scientists, academia and environmental professionals, 52% of the world population will be exposed to severe water scarcity by 2050, and continuing our current course will put at risk roughly $63 trillion USD, or the equivalent to 1.5 times the size of today’s entire global economy.

Food: Even assuming a 50% increase in agricultural efficiency, by 2050 we will need to increase the land space devoted to farmland 22 million square kilometers, an area equivalent in size to North America.

Oil: Searching for consensus about “peak oil,” the point in time when the maximum global rate of crude oil extraction is reached became a fool’s errand when the hydrofracking revolution only further polarized the debate due to deep uncertainty about the actual size of undiscovered world oil reserves. Many of the most popular doomsdates refer to current economically available oil and not total physically existing oil, as if extraction technologies will never improve and prices never adjust. So let’s just say that the most pessimistic analysts say “peak oil” has already occurred, while the most optimistic analysts say 2050.

Fish: In 2006, the journal Science published a four-year study written by an international group of ecologists from Canada, Panama, Sweden, Britain and the United States, which predicted that, at prevailing trends, the world will run out of wild-caught seafood in 2048— though the assumptions behind these claims have been widely disputed.

Fertilizer: The soil is running out of phosphate, a crucial ingredient in fertilizer required for farming. The most optimistic estimate for Peak Phosphate is 2050.

Land: Eighty percent of the world’s expanding megacities are sinking on a coast or river plain while sea levels rise. More than one million people move to cities each week, and by 2050, about half of the human population will live within 100 kilometers of a coast.

Humanity is poised to plunge in 2050. We can drown or we can float.

We don’t know enough about each subject to judge whether the 2050 deadline predicted in multiple domains is realistic, or a convenient focal point around which forecasters simplify their perception of trends. For instance, as recently as 2012, scientist and policy analyst Vaclav Smil argues that the famous 2009 Scientific American article on this subject of Peak Phosphate is balderdash. All we know is that through the ages, every Armageddon predicted by experts fails to occur, because humanity solves the problem. The bottomless source of solutions, as author Julian Simon argues in his classic book The Ultimate Resource, is human creativity.

What would you do with political freedom, almost limitless energy, and nearly half the earth’s surface?

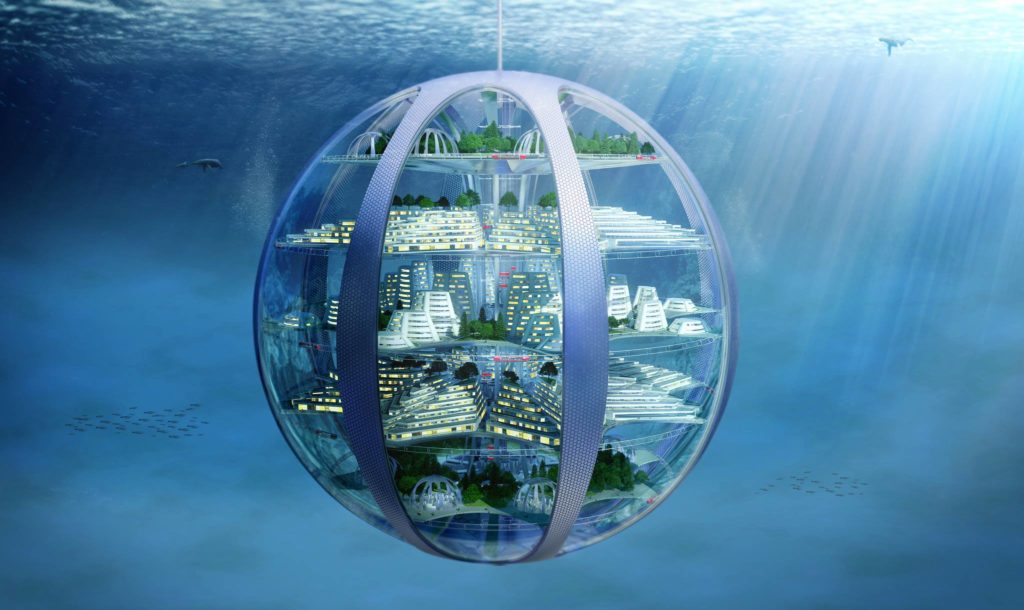

Underwater City Britain’s leading space scientist Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock unveiled the SmartThings Future Living Report, which predicts that within the next 100 years, sub aquatic communities will be commonplace. The surrounding water will be used to create breathable atmospheres, generating hydrogen fuel through the process. The report was commissioned by Samsung.

See the Sea

The globally emerging Blue Revolution became conscious of itself when Google engineer Patri Friedman realized that the economic theories elucidated by his grandfather, Milton Friedman, and developed by his father, David Friedman, would soon be put to the test by a rapidly approaching technology. Milton and David each asserted that political conflict was caused by political power, and that the solution to political conflict lay not in further consolidating power in the most virtuous government officials, but by the radical decentralization of power among millions of individuals with freedom and choice. How could such an organic bottom-up system work? David wrote The Machinery of Freedom describing the practical details, and Milton and his wife Rose wrote Free to Choose elucidating the moral principles. Millions were swayed by the ideas which have been vigorously discussed and debated ever since, but a practical full application of them was impossible. Friedmans proposed that humanity rethink society from the ground up. Unfortunately, all ground was claimed by existing governments.

A third-generation Friedman realized the assumption contained in the phrase “from the ground up” was the problem. Our terrestrially-trained minds are blind to the terrifying potential for tyranny in the power to claim land—fixed, immobile, where people have no choice but to live. At least since the agricultural revolution, humanity’s wealth and status had come from the power to control land and those who cultivate it. But that was about to change. A machinery of freedom was developing that would soon render citizens free to choose among governments, and disempower governments to claim monopoly control over land. To put Friedman theory into practice, all we had to do was imagine if civilization was founded not on “a solid foundation.” We do not, after all, live in planet Earth. Over two-thirds of our home’s surface is planet Ocean.

Our problem is not politics. Homo politicus, after all, is not going to stop politicking. The problem is one level deeper. It’s the medium in which humans compete to thrive. On static Planet Earth, the struggle must be to enforce power over our political opponents. On fluid Planet Ocean, however, solutions would emerge from granting power to our political opponents. Much of civilization’s capital is stuck to land and easily monopolized by dominant states, but “seavilization” could be disassembled and reassembled fluidly according to the choices of those who own the units. Imagine a thousand floating Venices with waterways for roads, except the components are modular. When individuals possessed the technology to settle the seas, they’d discover an aquatic world more than twice the size of Planet Earth, where citizens would engage in such fluidity of movement, tyrants would have a very hard time getting a foothold, and political power would be radically decentralized and shared. Floating cities which best pleased their inhabitants would expand, while others which failed to do so would decline and disappear. Democracy, a system by which majorities outvote minorities, would be upgraded to a system whereby the smallest minorities, including the individual, could vote with their houses.

David Friedman described a machinery of freedom. Milton Friedman advocated the freedom of choose. Patri identified a machinery of freedom to choose. In his personal blog, Patri proposed an idea that became contagious: Imagine ten thousand homesteads on the sea—“seasteads”– where ocean pioneers will be free to experiment with new societies. Aquatic citizens could live in modular pods that can detach at any time and sail to join another floating city, compelling ocean governments to compete for mobile citizens like companies compete for customers A market of competing governments, a Silicon Valley of the Sea, would allow the best ideas for governance to emerge peacefully, unleashing unimaginable progress in the rate at which we generate solutions to the oldest social problem: How do we get along? By such means, an economic and moral argument could become a technological experiment. In a blog called “Let a Thousand Nations Bloom,” Patri predicted that a process of trial and error on a fluid frontier will generate solutions we can’t even imagine today.

As if to confirm this prediction, pieces of a global puzzle coalesced around Patri’s proposal, as marine biologists, nautical engineers, maritime attorneys, and aquaculture farmers, many of whom thought they were laboring alone, approached Patri to propose astonishing solutions to global problems he never would have imagined.

A dozen mega-industries awoke from their collective slumber to discover that the colonization of the oceans was already underway. Japan inaugurated the Aquatic Age in the year 2000 when large aircraft landed on a thousand-meter floating airport in Tokyo Bay. In Singapore, the world’s largest floating football field, The Float at Marina Bay, hosted the 2010 Summer Youth Olympics. Three solar-powered floating islands, each shaped like a flower, were inaugurated on the Han River in Seoul, South Korea in 2011. India began installing a massive solar power plant on a 1.27 million square-meter floating platform in 2014, the same year that Japan built a floating solar array of the same size, equivalent to 27 Japanese baseball stadiums. The Dutch firm WaterStudio has designed a floating stadium which they propose could travel the world hosting the Olympic Games. Most extraordinary of all, Shimizu Corporation, a Japanese construction company that makes 14 billion US dollars a year, is holding fast to their deadline to have self-sufficient, carbon-negative botanical skyscrapers floating in Tokyo Bay by 2025.

A global movement of seasteaders believe the Aquatic Age is upon us, and if humanity is to solve our most pressing problems, we must build a blue, green civilization on blue-green algae. As we write, a team of volunteer seasteading lawyers is negotiating in talks with officials in several countries who want to host the first seasteads in their territorial waters and grant residents some measure of political autonomy. If all goes according to plan (and it never does), the first small floating city may take to the water around 2020.

All Hands On Deck

Seasteaders are a diverse global team of marine biologists, nautical engineers, aquaculture farmers, maritime attorneys, medical researchers, security personnel, investors, environmentalists, and artists. We plan to build seasteads to host profitable aquaculture farms, floating health care, medical research islands, and sustainable energy powerhouses. Our goal is to maximize entrepreneurial freedom to create blue jobs to welcome anyone to the Next New World.

The Seasteading Institute serves as a nonprofit think tank which takes a pragmatic and incremental approach to empowering others to build permanent settlements on the ocean. We envision a vibrant startup government sector, with many small groups experimenting with innovative ideas as they compete to serve their citizens’ needs better. The most successful can then inspire change in governments around the world. We’re creating this future because our governments profoundly affect every aspect of our lives, and improving them would unlock enormous human potential. Currently, it is very difficult to experiment with alternative social systems on a small scale; countries are so enormous that it is hard for an individual to make much difference. The world needs a Silicon Valley of the Sea where those who wish to experiment with building new societies can go to demonstrate their ideas in practice. At The Seasteading Institute, we believe that experiments are the source of all progress: to find something better, you have to try something new.

As a nonprofit, we’ve produced hundreds of pages of research in the key areas of engineering, law, and business development freely available at http://www.seasteading.org/overview/. Our primary engineering focus is on structure design. Seasteads should be safe, affordable, comfortable, and modular. Our law and policy program seeks to foster diplomatic relations with existing nations and industries. The Institute investigates viable business models that can take advantage of seasteads’ unique political and environmental features. Our current strategy centers around the Floating City Project through which we are crafting practical plans for the world’s first seastead, designed to satisfy the specifications of potential residents, and located within a “host” nation’s protected, territorial waters. As soon as we secure legislation for substantial political autonomy from a friendly host nation, we will invite businesses and residents.

Our efforts are entirely supported by at least a thousand people who have donated to the Seasteading Institute and hundreds who have volunteered their expertise and labor. We’ve been joined by over a hundred volunteer ambassadors from 23 countries who speak and educate about seasteading all over the world. About 3000 potential residents have filled out our Floating City Project survey, telling us what they want to see in their floating city.

Science Fiction is Science Fact

Floating cities? The idea strikes most people as fantastical. But thousands of structures the size of skyscrapers already ply the seas. Some cruise ships are two-thirds the size of the Empire State Building. Most cruise ships provide thousands of residents with food, power, water, service staff, safety, doctors, trash removal– most with more amenities than your average town. On these floating mini-cities, residents enjoy rock concerts, ice skating, opera, bumper cars, ballet, a 10-story waterslide, planetariums, Disney excursions, simulated skydiving, ice sculptures, robot bartenders, and more extravagances, all included in the price of the ticket.

If you step off an American or European coastal city, and step onto a cruise ship, your standard of living may rise, and your cost of living may drop. During the off-season, Celebrity Eclipse offers a 10-day transatlantic crossing from Florida to England, stopping at several Caribbean islands like the Bahamas, Puerto Rico, and Saint Maarten— at a cost of $31 per night, not counting tips. Want an ocean view? That’s $38 per night. We expect the price to drop rapidly as seasteading scales.

And scale it will. The global cruise ship industry is caught in a virtuous spiral of ascending profits, with markets doubling in size every decade. The enormous size of ships helps reduces the price each passenger pays, which compels more people to board them, which drives more revenue, which incentivizes the construction of ever bigger ships. In the 1990s, cruise ships rarely exceeded 2,000 passengers. By 2010 ships were carrying 6,000 passengers. If the cruise ship industry were a country, it would be ranked as one of the fastest in economic growth. Since 1980, the Gross Oceanic Product of the cruise ship industry has grown at more than twice the average annual rate of the Gross Domestic Product of the USA. This de facto self-governing ocean economy has remained immune to economic cycles of bubble and recession. For instance, during global financial crisis of 2008-2009, the growth of the global cruise market accelerated. In effect, people vacationed from mismanaged governments by choosing privately governed floating cities. In 2016, at least 22 million people, a population nearly equivalent to the island nation of Taiwan, will temporarily take to the sea.

The transition from temporary to permanent “resident-sea” is almost complete. In 2014, Shell, the oil and gas company, anchored the world’s largest floating offshore structure off the coast of Australia which will remain at sea for up to 25 years. A hundred and fifty feet longer than the Empire State Building is high, the Prelude Floating Liquefied Natural Gas Facility is built to withstand Category Five typhoons. The Prelude serves as a demonstration that technical challenges can be rapidly solved once a compelling business model is in place.

The Prelude is but a prelude of seasteads to come. It will be stationed 200 kilometers (125 miles) offshore. Park a dozen such floating skyscrapers next to each other, and we’d have a floating city with waterways for roads. If such a city were to float more than 200 nautical miles from shore – the outer limit at which a land government could assert any kind of jurisdiction – then its inhabitants would be free to start afresh with a new government. Beyond 200 nautical miles is the high seas, where ocean industries in cooperation with international governing bodies have developed a polycentric system of rules managing 45 percent of the planet’s surface which is unclaimed by countries.

The United Nations Convention on The Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), is an international agreement signed by 167 countries – excluding the United States which takes the position that UNCLOS reflects long-standing “customary international law.” UNCLOS defines the limits of a nation’s jurisdiction at sea in three zones of decreasing sovereignty. The first 12 nautical miles are a nation’s “territorial waters” where land governments have the same power they do on land. The area 12 to 24 nautical miles from the coast is a sort of buffer called the “contiguous zone” where a state may pursue vessels which break certain laws or pose a threat to the coastal nation. Beyond that each nation is entitled to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) that extends 200 nautical miles, or the length of its continental shelf, whichever is longer, where nations reserve the right to exploit natural resources such as oil and minerals below the surface of the sea, though the surface waters remain international waters. This means states won’t regulate “vessels” on the EEZ but they reserve the right to regulate “artificial islands, installations and structures.”

It gets complicated. Vessels traverse international waters under the jurisdiction of the country whose flag they purchase permission to fly. That means little islands of sovereignty from one nation sail through the 200-mile “exclusive economic zones” claimed by two other nations. As on all frontiers, legal jurisdictions on the sea overlap and are contested.

This can be a good thing. The law of the land isn’t as fluid as the law of the seas. The cruise ship industry flourishes in this flexible system of floating rules. Cruise ships dock in one nation, incorporate in another, and hire from anywhere. They pick and choose the national laws best suited to their industry, and through a sophisticated practice of “jurisdictional arbitrage,” flourish as semi-independent pioneer entities, while maintaining friendly alliances with all nations. Passengers sign a contract for onboard security and medical services with these freewheeling ocean skyscrapers that bring their own hospitals and security along with them.

So what nation do people belong to when they take a cruise? Don’t expect clarity if you ask the experts. Some legal scholars uphold the “floating territory doctrine,” which states that a vessel’s flag determines the jurisdiction of everyone on it. Opposing legal scholars reject this in favor of the “nationality princple,” by which nations retain jurisdiction over their citizens no matter where they travel. In many cases citizens are subject to several jurisdictions at once. Millions of people with conflicting legal statuses and contracts signed in different jurisdictions mingle on ships. It all works. In fact, it works so well, the average passenger on a cruise ship understands as little about his legal status as he understands about the ship’s engine— as is true with all mechanisms that work.

Cruise ships rarely stay in ports overnight. They drop off passengers, pick up supplies and more passengers, and go back to sea. This is an inconvenient way to run a mini-city. If seasteads remain permanently at sea, it’s easier to ferry goods and people to the floating city, rather than move the entire seastead to land every few weeks to pick up people and supplies. The vacationer’s dream: I wish my cruise would never end, becomes true if the ship doesn’t dock. If it doesn’t dock, it could remain in international waters. If it profits, it could expand without foreseeable limit. If it succeeds, others could proliferate. If people move there, they would be homesteaders on the high seas.

Excerpted from Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore the Environment, Enrich the Poor, Cure the Sick, and Liberate Humanity from Politicians by Joe Quirk and Patri Friedman. Free Press (2017). Amazon.