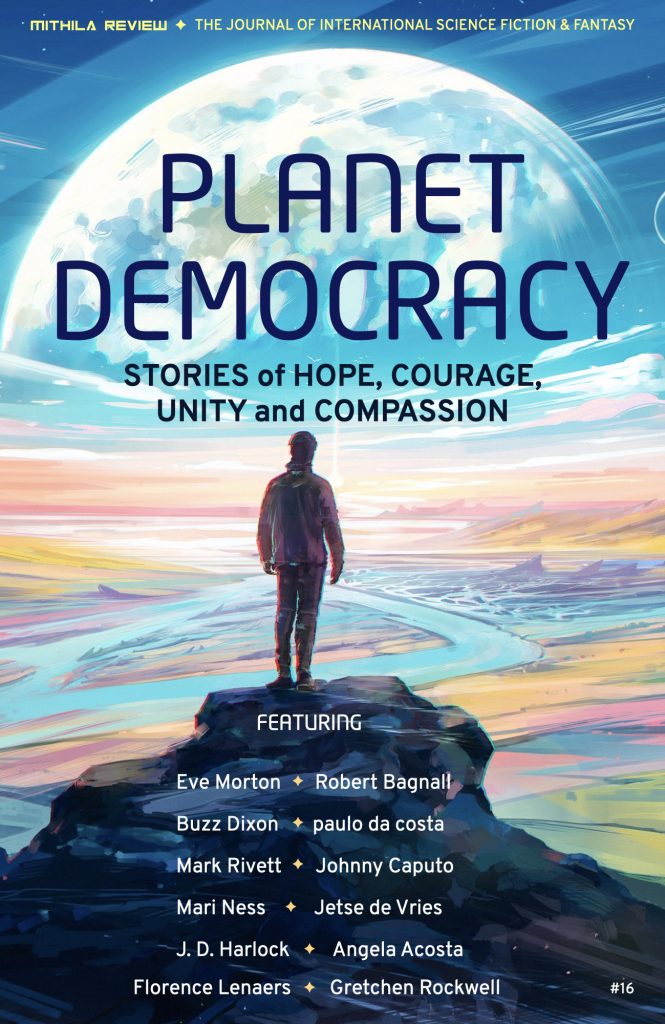

Planet Democracy: Stories of Hope, Courage, Unity & Compassion is a special edition of Mithila Review devoted to Hopepunk — a literature of resistance, which seeks to inspire compassionate thought and positive action.

Definition

Alexandra Rowland, who is said to have coined the term, described “Hopepunk” as a form of literature that is opposite of dark and dystopian fiction: “Hopepunk says that kindness and softness doesn’t equal weakness, and that in this world of brutal cynicism and nihilism, being kind is a political act. An act of rebellion.”

“Hope” and “punk” are the two key elements that make hopepunk interesting and powerful. Characters who don’t quit, who resist oppression, and fight for justice, for change, for democracy. There can’t be hopepunk, I think, without an underlying and undying faith in global democracy and freedom.

Genre definitions come after the fact, not before. The story comes first, not genre.

In her genre-defying story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” Ursula K. Le Guin raises profound questions about the fundamental nature of human suffering, and the price we must pay in our quest for happiness.

Imagine you have this perfect city with zero crime and misery for all but one child. Would you trade the joy and splendor of your perfect city, your perfect country for the suffering of a lone innocent child? Or would you reject the long-established belief or tradition of your people, and choose to walk away?

There’s a third choice: Would you rather stay and fight — like N. K. Jemisin wants us to — in the city of Um-Helat?

I think “Omelas” qualifies as a hopepunk story, even though it was written in 1973 — before the term’s inception.

Compared to Jemisin’s literary response to Guin “Those Who Stay and Fight,” I think Jemisin’s story “Emergency Skin” makes a far better hopepunk story.

—

Planet Democracy in Action

When we started Mithila Review in late 2015, it was an urgent plea for peace, tolerance and democracy during a time of an acute political crisis — a period of ultranationalism, radicalization and turmoil. And I’d like to believe that as a global science fiction and speculative community of visionary thinkers, storytellers, editors, publishers, all our readers and patrons, we have been able to make a small difference just by the act of existing, being, and bringing this community together.

As the founding editor and publisher of Mithila Review, my job has been anything but easy. Still I go to sleep peacefully each night knowing that we — you and I — are working to keep the hope for a peaceful, better and inclusive future alive for everyone on this planet. One cause, one special issue at a time.

In response to our call for submissions for an issue devoted to hopepunk, we received nearly two hundred stories from writers living and working in five continents. And I am truly grateful to each and every author who gave me the opportunity to read their precious work.

For long, I’ve resisted the idea of doing themed issues at Mithila Review because I like to give writers freedom to choose to speak their truths when the need is personal and urgent. As a writer, I know writing to a theme can be very difficult. We write when that creative dam inside us wants to burst, but the creative needs or writely muse usually doesn’t align with the theme or call for submissions.

Writing is action. Writing a hopeful and positive story of change and radical kindness is an act of courage, the essence of political activism. Sometimes it takes about a day, a week or a month, even multiple years, to write, rewrite, “finish,” and submit a piece of story. Let’s say it takes about a hundred hours to write and send a story. It’s roughly three weeks of an author’s life spent working on hope — for oneself and the others: readers. 200 submissions x 3 weeks = 600 weeks divided by 52 weeks/year. That’s almost twelve years’ worth of conscious thinking and action for a better world.

This special edition of Mithila Review — this radiant and collective act of hope — would not have been possible without the uniting vision and tireless efforts of Dr. Amy Johnson (editor: Drones & Dreams, 2019), and the invaluable support of the team and partners at the National Democratic Institute (NDI).

Once again, thank you so much, Amy, and the whole NDI team, specially Chris Doten, Maddy (Madeleine Nicoloff), Sarah Moulton and Caitlyn Ramsey, for giving us the perfect opportunity to facilitate and organize such a global movement to strengthen our democracy at a personal and global level.

—

Planet Democracy: Table of Contents

FICTION

In Robert Bagnall’s story “The Ones Who Scream America,” Quaker school teacher Sally Nodal fights against the voices she hears imploring her to hate. When the Secret Service traps her into helping them, she learns she’s not alone in hearing those voices, voices that define a poisonous zeitgeist. Realizing the enormity of it all, Sally fights back — and learns a bit about modern art along the way as well.

Buzz Dixon transports us to a blazing hot future in his cinematic story “Trucker,” where three of the last human truck drivers save a desperate mother and her child.

In Eve Morton’s story “Milkman,” two women band together to help feed a future of children who would otherwise starve.

In “This is My Home” by Mark Rivett, we come face to face with the power of technology and collective action in changing the world — whether we want it to or not.

“In The Rhythms of the World,” Johnny Caputo takes us to a distant time, where many of the ills caused by the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels have been mitigated by advanced plant and fungal technologies. But these bio-innovations don’t come free of consequences. Told from the point of view of a pollution-devouring fungus, this story explores the relationships between humankind, the technologies we create, and the incomprehensibly complex cycles of life of which we are but one part.

In “Harefoot Express,” Paulo da Costa transports us to a future that still holds hope for human existence, including more inclusive and democratic forms of governing, as well as new strategies for the long process of restoring the earth’s natural ecosystems and diminishing the human footprint. What will tourism and holiday travel look like a century from now? This is a time when individual limitations are accepted and understood in light of the collective steps necessary to move past a post-apocalyptic era and a more sustainable future.

In Jetse de Vries, “Zen and the Art of Gaia Maintenance,” humanity seems to have finally figured out what it means to be part of the solution and not the problem.

POETRY

Mari Ness’s poem “Horsemen” offers a brief moment of respite — a poetic break from the preceding fiction.

J. D. Harlock’s poem “Brighter Than The Last” melds solarpunk and sunshine noir to explore the harsher currents underlying our path to a solarpunk future.

In Angela Acosta’s “Paradise of the Abyss,” we travel to the Yucatán Peninsula and take a tour of a burgeoning civilization, Paradise of the Abyss. There, young Piedad learns how to revitalize Earth’s ancient impact crater using the knowledge of Mayan ancestors and million-world networks lightyears across.

In Florence Lenaers’ poem, she asks: What would a school curriculum offer in a hopeful future? Written as a poetical take on this question, “School of Continuing Education: Excerpt of the Course Catalog” crystallized from a twofold view of education: as both an interdisciplinary web & an indefatigably continuing endeavour.

In “In My Utopias,” Gretchen Rockwell presents a series of sonnets that imagines five different utopias, looking outward as well as inward to imagine hopeful futures.

Happy reading and sharing!

Love,

Salik

PS. Our generous patrons and readers like you make every issue of Mithila Review possible. Please don’t forget to subscribe and support us. Thank you!