“Fifty years in the making, India’s Space Programme is fulfilling the vision of its founders and delivering services from space that touch the lives of 1.3 billion people every day. In addition to operating a collection of satellites for weather, Earth observation, navigation and communication, today has a spacecraft orbiting Mars and a space telescope orbiting the Earth.

Gurbir Singh’s book The Indian Space Programme: India’s incredible journey from the Third World towards the First provides the big picture of India’s long association with science, from historical figures like Aryabhata and Bhaskara to Homi Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai, the key architects of its space program. It covers the scientific contribution of Indian scientist during the European enlightenment and industrial revolution through the work of physicist S.N Bose, experimentalist J.C. Bose, mathematician S. Ramanujan and Nobel Laureate C.V. Raman and others. It traces the technological development of Tipu Sultan’s use of rockets for war in the 1780s; the all but forgotten contribution of Stephen H Smith’s use of rockets as a means of transport in 1935 in northern India and the emergence of Sriharikota – India’s spaceport.

Key questions about the Indian Space Research Organisation covered in the book include: a detailed account on why a fishing village in Kerala was used to launch India’s first rocket into space on 21 November 1963. What are the types of launchers India has developed? How are ordinary people of India benefitting from the space programme? How India got to the Moon and Mars? What are the prospects for India’s ambitions in space for human spaceflight, military and science? In space will India compete or collaborate with China, USA and Russia? This detailed work in 645 pages, 29 tables and 9 appendices is richly illustrated with 140+ illustrations (some images published for the first time) and supported by over 1000 references. It is written for the non-specialist offering a big picture view of India’s space program – its history, current status and future ambitions, all in one place.” — Source: Amazon

Excerpts from Chapter 14: Human Space Flight

Without Gagarin, there would have been no Armstrong, asserted the Russian rocket engineer Boris Chertok (1912–2011). Yuri Gagarin from the USSR was the first man in space in 1961. Eight years later, Neil Armstrong from the US became the first man to walk on the surface of the Moon. Just as the US’s space programme was driven by the success of the USSR’s programme, the success of the Chinese Human Spaceflight (HSF) programme has been the impetus for that of India’s. China space program is operated by the China National Space Administration (CNSA) and started in the mid-1950s. The US has barred NASA from cooperating with CNSA but despite that, China has the most advanced space program after the US and Russia.

HSF is a natural aspiration for any national space programme and India is no different but there are suggesting that China’s HSF has been a motivation for India’s. China’s first spaceflight with an astronaut was completed in 2003, and by the following decade, China had flown ten astronauts, including a woman, in four flights. India has not launched any Indian’s to space and does not have an active Human Spaceflight program. ISRO presented plans for its HSF programme to the Prime Minister of India in October 2006 to secure funds and initiate the programme in April 2007. This timeline suggests that this was most likely triggered by China’s success of Shenzhou 5 in 2003 and Shenzhou 6 in 2005. However, a decade after presenting those plans, ISRO still does not have a formal approval from the government to proceed with its HSF programme.

From the outset, ISRO has been clear that its main objective is to use space to address the social and economic needs of the nation. HSF does not naturally fit into this vision. Apart from the enormous cost of HSF, any funds diverted to such a programme would not be available for ISRO’s earth observation and communication capabilities responsible for delivering those social and economic benefits. Besides, the vision of its founder Vikram Sarabhai explicitly excluded manned-spaceflight “There are some who question the relevance of space activities in a developing nation. To us, there is no ambiguity of purpose. We do not have the fantasy of competing with the economically advanced nations in the exploration of the moon or the planets or manned space-flight. But we are convinced that if we are to play a meaningful role nationally, and in the community of nations, we must be second to none in the application of advanced technologies to the real problems of man and society.”

Financial and political commitment aside, India lacks one of the key elements for a HSF programme, a heavy-lift launch vehicle. Even if a spacecraft qualified for a human crew and a fully trained human crew were available, India does not have a reliable human-rated launch vehicle to deliver the spacecraft to Earth orbit. However, the development of some critical elements associated with HSF are in progress. For example, a spacecraft re-entry experiment was conducted in 2007, a mock-up of a crew capsule was flown and recovered after a sub-orbital flight in 2014, and work is progressing on astronaut training facilities, space food and launch escape system.

India’s First and Only Astronaut Rakesh Sharma

Of India’s 1.3 billion nationals, only one has had the first-hand experience of spaceflight with direct support of the Indian government. Two astronauts with connections to India, Kalpana Chawla and Sunita Williams have flown as part of the American space programme. Four Indian astronauts (two from the Indian Air Force and two ISRO) have trained for a specific mission but only one went to space. In April 1984, Wing commander Rakesh Sharma (born 1949) from the IAF spent eight days aboard the Soviet space station Salyut 7 in LEO. India did not solicit the spaceflight but accepted after it was offered a second time by the USSR. The first offer was made by Leonid Brezhnev (1906–1982), leader of the USSR, in 1978 to the then Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai (1896–1995). Following a general election in India, Indira Gandhi was elected, and Brezhnev successfully repeated the offer to the new Prime Minister in 1980.

The offer to fly an Indian astronaut onboard the USSR’s space station Salyut 7 was part of the USSR’s wider Interkosmos programme and not an offer exclusively made to India. The Interkosmos programme was a part of the IGY objective to build international cooperation but also a strategy to extend the USSR’s political influence. In addition to India, nationals of 15 other countries, including Hungary, Vietnam, Poland, East Germany, Afghanistan and France, experienced spaceflight between 1978 and 1988 through the Interkosmos programme. The US pursued a similar dual pronged policy. India already had a strong relationship with the USSR going back to the early 1960s when the latter had played a key role in India’s very first rocket launch from Thumb and assisted in the launch of India’s first satellite in the 1970s. It was not just in space technology that India received offers of assistance but in other sectors, too, during the period of the Cold War. Through such offers of collaboration, both the US and the USSR attempted to persuade non-aligned nations, including India, to side with their respective geopolitical world view.

When the offer came from the USSR, ISRO was making progress with its INSAT satellite programme and developing the infrastructure on the ground to support it. Launch vehicle technology was still at an early stage. ISRO had achieved initial success with the SLV-3, but the PSLV was still more than a decade away. HSF did not feature in its plans, and ISRO could not justify investing time and resources to gain the experience of eight days of human spaceflight that had no foreseeable value once the mission was over. So, when the Prime Minister passed on the offer of a free spaceflight for an Indian astronaut, ISRO declined. The Prime Minister then approached the Indian Air Force (IAF). Upon receiving a positive response, she took the political decision in 1980 to proceed. She instructed ISRO to provide full support and, if possible, to design meaningful scientific experiments that could be conducted during the mission.

The search for a suitable candidate then commenced. Reminiscent of the secret plan under which the USSR had selected Yuri Gagarin for his flight in April 1961, a secret programme (named Pawan ‘the wind’ in Hindi) was initiated in India. Around 200 IAF test pilots volunteered for “something extraordinary” under this programme. It was only when the selection process reduced the number of candidates to a handful, and the medical tests started that the true nature of the mission, HSF, was disclosed to the applicants. All candidates were put through a series of medical, physical and psychological test at the Institute of Aviation Medicine (now the Institute of Aerospace Medicine). Four candidates were shortlisted, and they travelled to Moscow for further medical tests. Eventually, Ravish Malhotra (born 1943) and Rakesh Sharma were selected as the final two candidates. Although only one would undertake the spaceflight, both underwent identical training. The decision for Sharma to be part of the primary crew and Malhotra in the backup, was made prior to their arrival at Star City in Russia for training in 1982. Sharma was born in the town of Patiala in Punjab in 1949; two years after the country had gained independence. He had joined IAF in 1970, and with 50 hours of training in a Russian MIG 21 fighter, he was on the front line. By his 23rd birthday, he had completed 21 operational missions in defensive and offensive roles during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. After the war, he became a test pilot. Prior to being selected for the Interkosmos mission, Sharma and Malhotra had known each other and both trained at the National Defence Academy but their time there did not overlap. Malhotra had left before Sharma arrived. The National Defence Academy is a joint services academy of the Indian Armed Forces, where cadets of the three services (army, air force and navy) train together. In the 1970s, both had served at India’s Air Force Test Pilot School within the Aircraft Systems Testing Establishment in Bangalore. In 1974, Malhotra was selected for the USAF Test Pilots Course. He attended the class 74A at Edwards Air Force Base and graduated as an Experimental Test Pilot.

Figure 11: Soviet-Indian prime and backup crew from left- Yuri Malyshev, Ravish Malhotra, Rakesh Sharma, Georgi Grechko, Anatoly Berezov and Gennady Strekalov. Credit: Sputnik

Figure 11: Soviet-Indian prime and backup crew from left- Yuri Malyshev, Ravish Malhotra, Rakesh Sharma, Georgi Grechko, Anatoly Berezov and Gennady Strekalov. Credit: Sputnik

Following their selection and medical assessments, Sharma and Malhotra arrived in Moscow with their families on 20 September 1982 to begin their training. They were eventually rostered as Research Cosmonauts, Sharma as part of the primary crew and Malhotra in the backup. The primary crew (Commander: Yury Vasilyevich Malyshev (1941–1999), Flight Engineer: Nikolai Nikolayevich Rukavishnikov (1932–2002 – later Rukavishnikov was replaced by Gennady Mikhailovich Strekalov (1940-2004)) and Research Cosmonaut: Rakesh Sharma) and the backup crew (Commander: Anatoli Nikolayevich Berezovoy (1942–2014), Flight Engineer: Georgi Mikhaylovich Grechko (1931–2017) and Research Cosmonaut: Ravish Malhotra) underwent identical training. Should an illness, injury or any other issue prevent any one of the primary crew from flying, the backup crew would step in.

Figure 12: Soyuz Capsule Abort System that Helped Gennady Strekalov Survive a Launch Failure Six Months before His Flight with Sharma. Credit: NASA

The 18-month training included assessments, training in a centrifuge and weightless environment, simulations for launch and landing in the Soyuz launch vehicle and survival training to cater for the eventuality that during return the capsule may land in a remote location resulting in a delay between landing and recovery. Since this was a Russian programme, learning the Russian language was a key requirement. Malhotra had some experience with the Russian language. While at the National Defence Academy, he had selected Russian as his foreign language, but it was entirely new for Sharma, who found it to be the “most difficult part of the training.” On 26 September 1983, six months before their flight on Soyuz T-11, the primary and backup crews, including Sharma and Malhotra, watched the launch of Soyuz T-10-1. With a two-member crew, T-10-1 was to fly to Salyut 7 with a mission to augment its solar arrays. The launch did not go to plan. A fuel leak and fire resulted in the destruction of the launch vehicle and launch pad. The Capsule Abort System engaged removing the crew capsule from the top of the rocket a few seconds before a massive explosion engulfed the launch site. As an experienced fighter and test pilot, Sharma was familiar with such life-and-death situations. He did not tell his wife about the launch failure “as had been my practice right through my flying and testing career.” Gennady Strekalov, one of the two who survived that day, returned to the launch pad six months after his death-defying experience and sat alongside Sharma and Malyshev for another attempt to launch to Salyut 7 when Nikolai Nikolayevich Rukavishnikov (1932–2002) assigned as the flight engineer on Sharma’s flight fell ill.

Figure 13: Crew of Soyuz T-11 in Star City. (Right to left) Gennady Strekalov, Yuri Malyshev, Rakesh Sharma, Ravish Malhotra and Sharma’s wife, Madhu. 15 April 1984. Credit: Sputnik

Figure 13: Crew of Soyuz T-11 in Star City. (Right to left) Gennady Strekalov, Yuri Malyshev, Rakesh Sharma, Ravish Malhotra and Sharma’s wife, Madhu. 15 April 1984. Credit: Sputnik

On Tuesday, 3 April 1984, at 10:38, Rakesh Sharma with Commander Yuri Malyshev and Gennady Strekalov blasted off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome aboard the Soyuz T-11 spacecraft. Ten minutes later, Soyuz T-11 was in a 224 kilometre LEO. There was no repeat of the dramatic events of six months earlier. Sharma, a career pilot, used to looking out of a window when flying, found the absence of windows at launch unnerving. The navigation, cabin pressurisation and warning system displays were placed in front of the research cosmonaut’s seat and it was his duty to monitor the health of these systems during flight. As the only one of the crew without previous spaceflight experience, his role during launch was to monitor instruments and participate only if an emergency arose. None did. Twenty-five hours after launch, Soyuz-T-11 gradually caught up and docked with Salut 7, which had the crew of Salyut T-10 on-board since February. For the next eight days, the six cosmonauts lived and worked together onboard Soyuz-7.

Sharma adapted quickly to microgravity without any ill effects. A day after arrival, he spoke to the Indian Prime Minister from orbit. Reminiscent of President Nixon’s (Richard Milhous Nixon, 1913–1994) speaking to Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin during their historic Moonwalk in July 1969, this was the political highlight of Sharma’s mission. The brief conversation in Hindi with Prime Minister IndiraGandhi has come to define Sharma’s spaceflight. She asked him “Upur se Bharat kaise dikhta hae (how does India look from above)?” He replied “Saare jahan se acha (best in the world)”. His natural, spontaneous and unrehearsed response were words from the lyrics of a song he was very familiar with since his student days.

Sharma’s mission made a substantial contribution to a sophisticated science experiment called Terra. During April, the huge Indian land mass is clear and cloud free, unlike Europe and the northern latitudes. The Terra Experiment was the collective name for the study of India’s natural resources using data from a variety of sources, including photographic surveys of Indian territory with a multi-zonal MKF-6M apparatus and KATE-140 camera onboard Salyut 7. The images produced formed part of a larger collection, including visual observations and photographic surveys using hand-held cameras, aerial surveys and surface measurements of experimental sections of Indian territory by Indian specialists. The original plan involved Sharma taking images from orbit during the nine passes over India, which was increased to 11 in support of Terra. Around 2,000 images were taken from space during the mission and later added to ISRO’s remote sensing database. The database had been initiated almost a year earlier at the launch of India’s second remote sensing satellite INSAT-1B.

During the eight days in space, Sharma recorded biomedical data from his own body with equipment designed and built by ISRO scientists. He conducted experiments on the phenomenon of undercooling and microgravity and its effects on semiconductor alloys using silver and germanium. Sharma’s yoga experiment was the “most curious of the medical experiments.” It was designed to study the potential of yoga techniques to mitigate the harmful effects of weightlessness on the human body; bones and muscles tend to deteriorate in extended periods of microgravity. Collectively, the crew conducted 43 experiments over the eight days of the mission.

Sharma went to space aboard Soyuz T-11 on 3 April as the 138th person to enter space and returned to Earth aboard Soyuz T-10 on 11 April, landing as planned in the USSR 46 km to the east of the city of Arkalyk. The return to Earth, potentially as hazardous as the launch, was also incident free, although Sharma recalls that the sound of the parachute cables chafing against the brackets was very unnerving “I was certain that the parachute was going to part company.” After his successful flight, he was awarded two medals by the USSR, Hero of the Soviet Union and The Order of Lenin. This was an integral part of the Interkosmos programme, a package deal that all foreign cosmonauts received. Sharma is the only Indian recipient of these awards and with the demise of the USSR on 26 December 1991, will remain so. From the Indian government, he received the Ashok Chakra, and in the interest of diplomatic consistency, the two Russian crew were also awarded the Ashok Chakra.

Speaking to the media about his experience, Sharma endorsed passionately the role of international collaboration. Not the collaboration of Interkosmos, which was driven by narrow political objectives of the Cold War, but one borne out of a grander recognition that future space exploration should be conducted by people from planet Earth and not just by representatives of a few of its nations. He advocates the idea that not every nation should have to reinvent the wheel, nor should they have to develop from scratch their HSF programme. It would not only prevent plundering the meagre resources of planet Earth but also not undermine the collective enterprise that human space exploration ought to be. Sharma is not keen on being defined by his spaceflight, nor is he preoccupied with it but is bemused that others are “It was just an event. It was given to me. I did it, and I want to move on”. It was no “cakewalk” he insists, but it was not as fulfilling as it would have been had he been a career astronaut’.

As a backup pilot, Ravish Malhotra was never called up. Following the joint celebratory tours around India, he returned to his career as a test pilot. Malhotra declined an offer to return to the USSR as an air attaché and turned instead to the private sector and worked for an aerospace company. Since his return in 1984, he has never been back to Russia. Following his spaceflight, Sharma returned to the IAF as a Flight Commander with an operational squadron before joining Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd. as chief test pilot. Later he headed the aerospace and defence division of an American Software Company in India.

Figure 14: Rakesh Sharma with Hero of the Soviet Union and The Order of Lenin Awarded by the USSR. August 2013. Credit: Gurbir Singh

From ISRO’s perspective, the flurry of media interest upon Sharma’s return to India was followed by nothing; just as ISRO had. Even though the eight-day-long spaceflight was a great morale boost for the nation, Sharma’s flight, in the absence of a coherent Indian plan for HSF, has remained one of the “isolated artefacts of curiosity.” However, even before Sharma had completed his mission, a demand arose again for another Indian astronaut. This time, it was not from the USSR, but the US.

Still-born Astronaut

By the time Sharma’s mission ended, the American Space Shuttle had been flying successfully for three years. To recover some of the huge costs, a commercial objective was built into the Space Shuttle programme from the outset. NASA was looking for ways to promote the Shuttle’s commercial potential and offered to fly a payload specialist as part of the commercial deal to launch a satellite from the Space Shuttle. This also served as NASA’s attempt to counter, compete with or simply emulate the USSR’s Interkosmos programme.

India was encouraged by the 1975 SITE programme to have its own communication satellite programme, resulting in the Indian Satellite (INSAT) series. ISRO commissioned four satellites of the first INSAT series (INSAT-1A through 1D) from the US-based Ford Aerospace and Communication Corporation. INSAT-1A was launched by a Delta launch vehicle in April 1982, and INSAT-1B was launched by the Shuttle in August 1983. INSAT-1C was assigned to mission STS-61-I for launch by the Space Shuttle Columbia on 25 June 1986. It would be launched along with three other payloads and a crew of five (including an Indian astronaut) for a seven-day mission. Once the agreement was signed, the search for an Indian payload specialist to join the crew was initiated. Since INSAT was an ISRO project, the proposed astronaut was to be from ISRO, not the IAF.

Figure 15: N.C. Bhat and P. Radhakrishnan. Credit: Bert Vis

Figure 15: N.C. Bhat and P. Radhakrishnan. Credit: Bert Vis

Initially, 400 volunteers with science and engineering backgrounds applied from various ISRO centres. Forty were shortlisted for further assessment, including a week-long screening consisting of medical, stress and psychological tests. In the summer of 1985, seven candidates were invited to a final selection board headed by Professor U.R. Rao and included Rakesh Sharma and NASA astronaut Paul Joseph Weitz (born 1932). The panel selected two candidates, Paramaswaren Radhakrishnan (born 1943), a scientist from VSSC in Trivandrum, and Nagapathi Chidambar Bhat (born 1948), an engineer from ISRO Satellite Centre in Bangalore. The candidates had to complete additional medical tests determined by NASA at the Johnson Space Centre. ISRO chose to make the public announcement on the candidate selection only after the tests in the US were complete. Until such announcement, both were prohibited from sharing the decision publicly. In July 1985, both candidates flew out to Huston, Texas, and successfully completed the medical evaluation.

Radhakrishnan, as a 22-year-old electronics engineer, was recruited in 1966 to INCOSPAR, which in 1969 became ISRO. He had established a strong connection with the American space programme from the outset. As a new recruit, Radhakrishnan’s first role was to visit schools, colleges and universities as part of a three-member team teaching students about spaceflight. He crisscrossed India for almost a year using a NASA-supplied Chevrolet truck loaded with models of rockets, satellites, Apollo modules and cine film of rocket launches. In 1966, the US was still developing the Apollo programme (the Saturn 5 launch vehicle and Command, Service and Lunar Modules) that would take Americans to a return journey to the surface of the Moon. Later Radhakrishnan served in ISRO in numerous roles including the design and development of the power system for India’s first satellite, Aryabhata

Bhat joined ISRO in 1973 just as India’s satellite programme was getting underway. Based at the ISRO Satellite Centre in Bangalore, he contributed to several of ISRO’s key space missions. He was involved in fabricating several elements for ISRO’s first satellite Aryabhata, the solar panel unfurling mechanism for IRS-1A, the antenna used on-board India’s first Moon mission Chandrayaan-1 and some of the experiments on SRE-1 in 2007, India’s first spacecraft that returned to Earth after 12 days in space.

Figure 16: P. Radhakrishnan (back row third from left) and N. C. Bhat (back row third from right) during High-altitude Training with the Indian Airforce. 1985. Credit: N.C. Bhat

Figure 16: P. Radhakrishnan (back row third from left) and N. C. Bhat (back row third from right) during High-altitude Training with the Indian Airforce. 1985. Credit: N.C. Bhat

Radhakrishnan was concerned that his age, 41, would work against him. He remembers a series of progressively tougher tests during the selection process, which included “countless questionnaires to fill in, and endless interviews, which mostly consisted of a monologue from the candidate, punctuated occasionally by a prompting question from the other side. The purpose was to probe into the deepest crevices of the candidate’s mind.” Bhat recalls the use of eye drops to dilate the pupil so that pictures could be taken of the retina. He unnecessarily suffered from blurred vision for three days before his sight returned to normal “Later, I came to know that they had forgotten to put another eye drops which restores the dilated pupil to normal.”

Preparation for the mission started following the successful medical tests conducted by NASA. The training included learning about the technical details of the INSAT satellites, how they were built, readied for launch and operated once in orbit. Both candidates visited the ISRO Satellite Centre in Bangalore, National Remote Sensing Agency (now National Remote Sensing Centre) in Hyderabad and SAC in Ahmedabad. Their training included gaining familiarity with high G forces in a centrifuge and altitude flights with the IAF.

The launch of INSAT-1C was scheduled for November 1986. During a five-day mission, the payload specialist would help prepare and launch INSAT-1C from the Space Shuttle cargo bay while in LEO. As with all space missions, there were a primary and a backup crew. The decision for primary/backup crew was to be made in September, that is, two months before launch. Until then, both would undergo identical training in India and the US. The Institute for Aerospace Medicine familiarised them with the space food that was being prepared by the Defence Food Research Laboratory (DFRL) in Mysore. The DFRL had provided food for the series of Indian Antarctic missions, as well as Sharma’s visit to Salyut 7. In addition to the NASA supplied food aboard the Space Shuttle (72 different items and 20 beverages), the Indian astronauts would take Indian space food, too. The preliminary group of 12 foods suggested by the DFRL included peas pulav, chicken pulav, lemon rice, chicken masala, peas paneer, kheer rice pudding, pineapple juice, mango juice, grape juice, sooji halwa, mango fruit bar and chapattis.

Then, on 28 January 1986, Space Shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after launch. Radhakrishnan and Bhat were at Ford Aerospace in the US for familiarisation with the INSAT spacecraft. They did not see it live but an hour afterwards on TV. They described the horror of seeing the death of seven astronauts as “very tragic and touching.” The incident sent shock waves across the US and space agencies around the world. The spectacular destruction during the launch of the most sophisticated spaceship ever built and the largest loss of life in a single US space incident brought NASA to an existential crisis. NASA’s initial statement indicated that the Space Shuttle mission would be rescheduled within six months, and ISRO’s provisional response was to proceed on that basis. However, the magnitude of the incident dictated that a longer period of review would be necessary. Radhakrishnan concluded that his dream of spaceflight “went up in smoke in that moment.”

It wasn’t just the Indian satellite and the astronaut flight that was impacted. Investigation of the Challenger accident was completed and the report published on 29 October 1986. Before the end of the year, on 27 December 1986, President Reagan (Ronald Wilson Reagan, 1911–2004) issued a directive asserting that the Space Shuttle “shall no longer provide launch services for commercial and foreign payload unless those spacecraft have unique, specific reasons to be launched aboard the space shuttle.” Before the accident, two dozen Shuttle flights (there were four shuttles in total) were scheduled per year. Afterwards, it was just 14 flights per year. In practice, it was even lower. Between the first and last Shuttle flights (12 April 1981 and 16 May 2011), 135 space missions were completed averaging to about 12 missions per year. The mission to launch Indian communication satellites from the Space Shuttle ended abruptly, and with it, the hopes of two Indian engineers who had suddenly acquired and then lost the opportunity of spaceflight. On that news, Radhakrishnan concluded, “so here I am, a still-born astronaut.”

Roadmap for Human Spaceflight

ISRO’s HSF programme has had several false starts. In 2006, over 80 senior scientists met at ISRO headquarters in Bangalore concluding unanimously that time was right for ISRO to proceed with its HSF. India’s Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007–20012), stated “The development of a manned mission would take about 10 to 12 years, and it is planned to focus on developing critical technologies required during 11th plan period and achieve substantial progress towards realising a manned mission during 12th plan period”.

A mission with specific objectives related to a human crewed spacecraft was completed in the following year when ISRO demonstrated its ability to launch and recover a 550-kilogram module in January 2007. SRE-1was ISRO’s first attempt to recover a spacecraft it had launched. Following the launch aboard a PSLV and twelve days in Earth orbit, the capsule was remotely commanded to de-orbit and was recovered by the Indian coast guard after splashdown in the Indian Ocean. In addition to basic on-board microgravity experiments, ISRO tested the capsule’s navigation, guidance and control systems. The recovered SRE-1module is now a key exhibit in ISRO’s space museum in St. Mary Magdalene Church, the cradle of India’s space programme located within the grounds of VSSC in Kerala.

Figure 17: Space Recovery Experiment Capsule on display at VSSC. Credit: ISRO

Figure 17: Space Recovery Experiment Capsule on display at VSSC. Credit: ISRO

SRE-1was an important step towards the HSF programme. Its success helped ISRO secure a $2.1 million (Rs.8.5 crore) feasibility study on HSF. Six months after SRE-1, in June 2007, ISRO chairman constituted a steering committee on Human in Space Programme. The committee produced a four-volume report by early 2008 consisting of a project report, cost estimate, executive summary and a prologue. This report was submitted to the government in February 2008. So, by mid-2008, ISRO had a clear vision on how its HSF programme would develop based on detailed research, feasibility studies and a successful re-entry mission. By the end of the year, an opportunity arose for potential international collaboration that could hasten the programme timeline compared to ISRO’s doing it alone. A MoU was signed following Russian President Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev’s (born 1965) visit to India in December 2008. The Russians were probably influenced by India’s success with SRE-1in 2007 and ISRO’s first and highly successful mission to the Moon, Chandrayaan-1, which had been launched three months before Medvedev’s visit. Under this agreement, Russia would fly an Indian astronaut aboard a Russian spacecraft by 2013 and help India build its own spacecraft capable of carrying a human crew based on the Soyuz design for launch by GSLV-Mk3 by 2016.

Buoyed by the success of SRE-1, Chandrayaan-1 and the prospects of rapid progress through the Russian MoU, the ISRO chairman Kasturirangan unveiled plans for two- and three-member crew modules designed for a week-long space mission during the 96th Indian Science Congress in January 2009. K. Radhakrishnan, the VSSC director at the time but became ISRO chairman about nine months later, was also present. He also spoke about an Indian space mission by Indian astronauts in an Indian spacecraft, along with missions to the Moon and Mars. One spectacular media headline that followed was “India plans to hoist tricolour on the Moon by 2020.” In 2009, the Government of India, too, appeared to be in favour not only of HSF but also of a human mission to land on the Moon by 2020.

India’s plans were very likely motivated by the September 2008 success of the Chinese Shenzhou 7 mission, which carried for the first time a crew of three. By 2016, China successfully completed 6 missions carrying 15 astronauts, 13 men and two women (Shenzhou 5 on 15 October 2003 with one astronaut; Shenzhou 6 on 16 October 2006 with two; Shenzhou 7 on 25 September 2008 with three; Shenzhou 7 on 25 November 2008 with three; Shenzhou 9 on16 June 2012 with three; Shenzhou 10 on 11 June 2013 with three and Shenzhou 11 on 17 October 2016 with three). Ostensibly, India is not in a space race with China, but in 2014, ISRO revealed that it prepared its mission to Mars in haste only after the Chinese mission to Mars, Yinghuo-1, aboard a Russian rocket failed to leave Earth orbit in November 2011.

Over the next couple of years, the HSF programme made no real headway. The following year, 2010 was not a good year for ISRO. The MoU with Russia had not been productive and was terminated in October 2010. Why that happened is unclear, but probably because India and Russia could not agree on the commercial arrangements underpinning the technology transfer of Soyuz from Russia to India. Two GSLV launches, GSLV D3 in April and GSLV F06 in December, failed during launch.

The Twelfth FYP (2012-2017), published in 2011, merely restated the Eleventh FYP objective to “develop the critical technology and subsystems related to Human Space Flight programme”, confirming that, between the 11th and 12th Plans, India’s HSF programme made no major progress. Unexpected media statements in 2012 from the IAF, claiming that the IAF was proceeding with the astronaut crew selection process, added to the confusion. The source of the confusion was to some extent competitive posturing between the IAF and ISRO. The IAF has had a strong connection with the HSF in the past. Astronaut training is centred around the Institute of Aerospace Medicine which is an IAF body, and the first astronaut, Rakesh Sharma, was a wing commander in the IAF.

At the end of 2013, ISRO issued a press release insisting that media reports on Manned Mission to Moon were unfounded. Despite the absence of an essential element, the heavy launch vehicle, ISRO has been quietly making progress towards human spaceflight capability. In March 2012, the Minister of State confirmed in the Indian parliament that Rs.145 crore ($22.5 million) had been allocated for ISRO to pursue the development of critical technologies for the HSF programme. These funds were split between various tasks: Rs.61 crore ($9 million) for the crew module, Rs.27 crore ($4 million) for qualifying the launch vehicles for a human crew, Rs.36 crore ($5.5 million) for contracts with institutions and Rs.21 crore ($4 million) for other tasks, such as crew module aerodynamics, space suits and life support systems. A mock-up of the crew capsule was tested in a sub-orbital flight on 18 December 2014 as the LVM3-X/CARE mission, a sub-orbital version of the SRE-1 but using the LVM3 with a non-active cryogenic third stage.

The HSF programme is not one of ISRO’s priorities, but with the allocated funds, it has been quietly working on the development of an astronaut training programme and an astronaut crew capsule under the guidance of a dedicated project director for the HSF programme. Progress is being made in many key prerequisites, including space suits, environmental and life support systems, and emergency Capsule Abort System at the launch pad and during the early phase of launch. Since March 2009, ISRO has had a MoU with the IAF’s Institute of Aerospace Medicine to conduct basic research on the physical and psychological requirements for the human spaceflight crew and expand the institute’s existing facilities to cater for the HSF programme as a pre-project R&D activity.

Figure 18: Crew Module in the Andaman Sea after Splashdown. 18 December 2014. Credit: ISRO

Figure 18: Crew Module in the Andaman Sea after Splashdown. 18 December 2014. Credit: ISRO

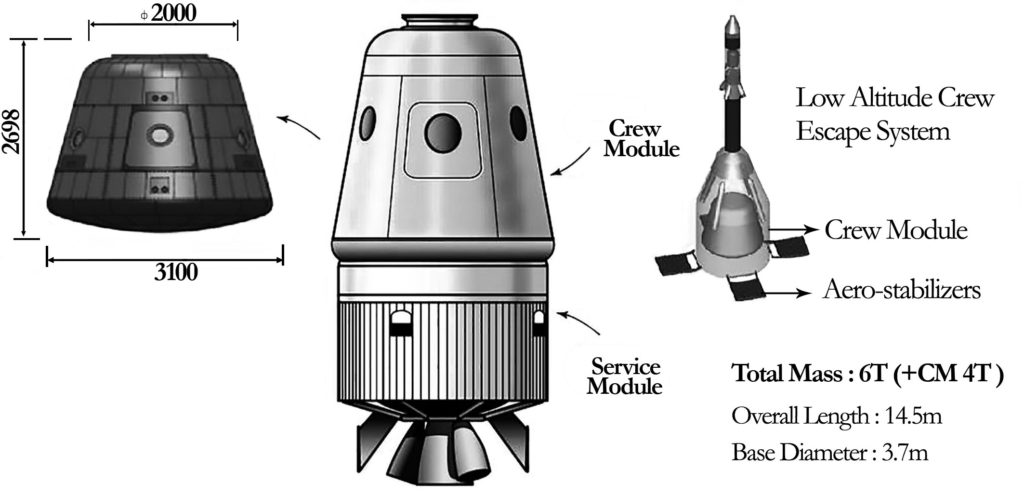

ISRO has also entered agreements with a Bangalore-based third party to initiate the development of spacesuits and a Mysore-based company to develop a space food menu for Indian astronauts.The initial plan envisaged a crew module designed for two, but this has since been expanded to include a 3-astronaut variant. Preliminary designs indicate that the crew module will be a twin-walled structure with a sealed, all-welded internal shell.

A service module with a re-entry engine is to support the crew module. Initial plans call for a mission duration of a few hours for the first mission that could be extended up to seven days. The orbit has been designed to allow the crew capsule to re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere automatically in the event of a service module engine failure. The capsule would be launched from Sriharikota using GSLV-Mk3/LVM3 return for a splashdown in the Bay of Bengal or the Indian Ocean. The crew module is designed with some capability to manoeuvre in the atmosphere along both down and across ranges to support navigation to a predetermined splashdown location.

Once the launch vehicle (LVM3) is ready, integrated tests with the crew module, including the Emergency Capsule Abort System (CAS), can commence. The CAS is a small rocket at the top of the main launch vehicle. In an emergency, it fires like an ejector seat (but is located above the crew) and pulls the crew capsule away from the launch vehicle for a parachute landing a few kilometres away from the launch pad. Prior to the first human orbital flight, multiple test-flights of the crew module in orbit with dummy passengers and non-human occupants (the US had used a chimpanzee, the USSR used 4 dogs and the Chinese had used rats and guinea pigs. These initial missions test various subsystems, including life support, guidance, navigation and re-entry. The USSR had conducted seven flights without human occupants using varying sophistication in the onboard subsystems before Yuri Gagarin’s historic flight on 12 April 1961.

Figure 19 Proposed Crew Vehicle (left), Crew Module Attached to the Service Module (centre) and the Emergency Capsule Abort System (right). Credit ISRO

The crew capsule of each version was an improvement on the previous. Only three of the seven flights were completely successful before Gagarin made his attempt. Between 1959 and 1961, the US too conducted over a dozen tests on the ground and sub-orbital launch on their Mercury spacecraft before America’s first astronaut Alan Shepard’s (1923–1998) flight in May 1961. China conducted four test flights of their Shenzhou spacecraft before their first human spaceflight with Yang Liwei (born 1965) in 2003. ISRO had planned to follow-up SRE-1 with SRE-2, but following a series of delays, SRE-2 has been quietly withdrawn. ISRO’s 2014 LVM3-X/Crew Module Atmospheric Re-entry Experiment test flight was sub-orbital, and the crew module was of an initial rudimentary design. Since then, ISRO has not scheduled any additional test flights of the crew module, so a date for India’s first flight with a human crew is not imminent and remains unknown. The success of India’s HSF programme will be measured more in terms of political and national prestige than results in science or technology.

The HSF programme will require a profound shift in ISRO’s capability and capacity, but success will not translate into meaningful national economic benefits for which ISRO was established. Further, the high cost of HSF may well delay or prevent its other objectives. Kasturirangan, who became ISRO chairman in 1994, understood the scale of the challenges inherent in the HSF programme and noted “People give you a wrong impression about the type of resources needed for human space mission” and the “returns will never be big.” Ten years ago, India committed to a desire for HSF but ISRO still has no formal government approval to proceed. In its absence, ISRO is undertaking work on some aspects of HSF in the background.

The story of Indian astronauts is a short one. Rakesh Sharma continues to speak and write about his experience and the future for India’s HSF programme. A recent announcement indicated that Bollywood film about his experiences is underway. Kalpana Chawla, was killed when Space Shuttle Colombia disintegrated during re-entry over Texas on 1 February 2003. Announcements about a film about her career have also been published but here former husband, Jean-Pierre Harrison has insisted in the past that he does not support the project..

Ravish Malhotra retired from his work in the private sector and is not actively involved in any space projects. P. Radhakrishnan continues to live in Kerala where he frequently participates in the media as a science communicator in both his native Malayalam and English. N.C. Bhat retired in 2011 from ISRO but continues to share his experience in mechanical design as a consultant. Since 2015, he has been involved with Team Indus in support of their lander and rover mission to the Moon. Sunita Williams completed two spaceflights to the ISS and clocked up a total of over 300 days in space and over 50 hours of spacewalk. She is now part of a team of astronauts preparing to fly the next generation of US’s commercially built human-rated spacecraft from Boeing CST-100 and Space-X Dragon.

Each national government that has launched humans into space started with men and then included women. The Soviets put the first woman in space in 1963, two years after the first man. The gap between the first male astronaut and its first female astronaut for the US was 22 years. The Chinese took just nine years. In early 2016, the IAF Chief Arun Raha announced that women in the IAF could qualify as fighter pilots. Perhaps, India’s first man in space could be a woman.

Excerpted from Gurbir Singh’s The Indian Space Programme: India’s incredible journey from the Third World towards the First available on Amazon and other stores.

Footnotes:

1. To quote Boris Chertok “I contend that if Gagarin’s flight on April 12th, 1961 had ended in failure, U.S. astronaut Neil A. Armstrong would not have landed on the Moon on July 20th, 1969.” Chertok, Boris and Asif A. Siddiqi. 2009. Rockets and People Volume III: Hot Days of the Cold War. NASA. Retrieved from http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4110/vol3.pdf. P79

2. The terms astronaut and cosmonaut are currently used interchangeably depending on where and who is using them. The US uses the term astronaut, the Russians use cosmonaut, the Chinese taikonaut, and it may turn out that India may use the term Vyomanout. In China, the term hangtianyuan is also gaining popularity. See http://archive.defense.gov/pubs/20030730chinaex.pdf. I use the term astronaut only for convenience and consistency.

3. Quoted from Sarabhai’s speech on 2 February 1968 during the ceremony for formally dedicating the Thumba launch site to the United Nations. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was present for the ceremony.

4. Rao, U. R. 2014. India’s Rise as a Space Power. First edition. Delhi: Cambridge University Press India Private Limited. P86

5. Interview with Rakesh Sharma in August 2013. See http://astrotalkuk.org/2013/11/03/rakesh-sharma/. For fascinating details on the USSR’s secret plan under which the first six cosmonauts, including Gagarin, were selected, see Burgess, Colin and Rex Hall. 2009. The First Soviet Cosmonaut Team: Their Lives and Legacies. Springer Science & Business Media. P18

6. Me too in 1958.

7. Interview with Ravish Malhotra. 11 October 2013.

8. Nikitin, S. A. 1985. The Space Flight of the Soviet-Indian Crew. NASA TM-77615. P6. Retrieved from http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19850012916.pdf. The original report was produced by the Interkosmos Council, USSR Academy of Sciences, in July 1984. The English version was made available by NASA at the link given.

9. Gennady Strekalov, the flight engineer aboard Sharma’s flight, had narrowly escaped a launch pad fire and explosion on 26 September 1983, thanks to the Soyuz abort system.

10. On 18 March 1965, two cosmonauts in Voskhod-2 landed 400 km away from their designated target and had to spend two nights in their capsule with night-time temperature of -25oC. Survival training and their familiarity with the region was crucial in the eventual safe recovery.

11. Interview with Rakesh Sharma in August 2013. See http://astrotalkuk.org/2013/11/03/rakesh-sharmaa

12. Email exchange with Rakesh Sharma. April 2016

13. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salyut_7 for a list of all the Salyut 7 missions that took up 27 cosmonauts between 1982 and 1986.

14. Despite the extensive speculation to the contrary in the media, these words were not rehearsed. Interview with Rakesh Sharma in August 2013. See http://astrotalkuk.org/2013/11/03/rakesh-sharma/

15. Nikitin, S. A. 1985. The Space Flight of the Soviet-Indian Crew. NASA TM-77615. P9. Retrieved from http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19850012916.pdf.

16. Ibid

17. Interview with Rakesh Sharma in August 2013. See http://astrotalkuk.org/2013/11/03/rakesh-sharma

18. Ibid

19. Personal communication with Rakesh Sharma dated 9/10/2013.

20. This was the conclusion of Professor U.R. Rao, who became the ISRO Chairman in 1984, the same year as Sharma’s flight. Rao, U. R. 2014. India’s Rise as a Space Power. First edition. Delhi: Cambridge University Press India Private Limited. P90

21. The astronaut flight would cost an additional Rs. 2 crore (about $300,000) according to an undated India Today clipping provided by N.C. Bhat.

22. This information has been sourced from NASA’s Flight Assignment Baseline (FAB) document. It shows that the booking date for the launch was 13 November 1982, though it was common for the FAB to be amended multiple times to reflect operational requirements. Dr David Baker, who worked on flight manifests at NASA headquarters during the early 1980s, supplied this information from his personal archives. Following the loss of Challenger on 28 January 1986, the mission STS-61-H was reassigned to another crew and payload but was eventually cancelled altogether. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/STS-61-H

23. Email correspondence with P. Radhakrishnan. 13 September 2013

24. These details were included in an article published in an ISRO in-house magazine called Upagrah made available by N. C. Bhat.

25. In February 1985, less than a year after Sharma’s flight, Salyut 7 was almost lost. Whilst unmanned, it lost communication with Earth and a special rescue mission was launched to rescue it. In the meantime, a fantastical and false story emerged in which the American Space Shuttle was to be used to kidnap Salyut 7 from orbit to steal sensitive military secrets. This was further promoted by a Russian documentary by Roscomos. Bart Hendrickx wrote a factual account available here http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2554/1

26. Ibid

27. This quote comes from an article published in an Indian newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, on 9 March 1986.

28. A classified US report indicated that a “New Delhi is likely to keep its payload specialist on standby for a future shuttle flight – perhaps to launch the INSAT-1D satellite scheduled to be ready in 1989”. CIA Report “India: Space Satellite Options), 23 July 1986, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP86T01017R000302820001-5.pdf P4

29. Email communication with P. Radhakrishnan. 13 September 2013. The full quote is as follows “Bhat and I were in Ford Aerospace, USA, for familiarisation with INSAT spacecraft, when we watched on the TV the Challenger flight on January 28, 1986. A little over a minute into the flight, the Shuttle blew into a ball of fire shattering my lifetime dream. Just as steeply as my hopes had soared high into space barely a year earlier, it now made a nosedive. I clearly remember the first question to me from the Selectionboard in 1985 “Why are you in this?” My answer was, “for thrill, excitement and adventure, and also to have something to tell my grandchildren.” All that went up in smoke in that moment.

30. National Security Decision Directive Number 254 27/12/1986. 1986. National Security Council. Retrieved from https://reaganlibrary.archives.gov/archives/reference/Scanned%20NSDDS/NSDD254.pdf.

31. Fought, E. Bonnie. January 1988. Legal Aspects of the Commercialization of Space Transportation Systems. Berkley Technology Law Journal 3 (1). Retrieved from http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1068&context=btlj.P103

32. The following resource describes each Space Shuttle mission in thorough detail. https://spaceflight.nasa.gov/outreach/SignificantIncidents/assets/space-shuttle-missions-summary.pdf

33. From an account written in 2009. The full text is available in MS Word format here (with the consent of the author): https://gurbir.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/My_Flirtation_With_Space.doc

34. For ISRO’s press release on this meeting, see http://www.isro.gov.in/update/07-nov-2006/scientists-discuss-indian-manned-space-mission

35. Post-independence, Indian Prime Minister Nehru chose to centralise India’s national economy using the concept of a five-year plan that was common particularly among countries governed by socialist governments. There is not one but a series of five-year plans; each government department has one. The first plan covered 1951–56. The current 12th plan was published by the Planning Commission in 2011 and covers the period 2012–2017. With minor breaks, India has consistently pursued the five-year plan approach since independence. Previous plans are available here: http://www.planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveyr/welcome.html

36. Priyadarshini, Subhra. 3 January 2009. ISRO Unveils Manned Mission Design. Nature India. Retrieved from http://www.natureasia.com/en/nindia/article/10.1038/nindia.2009.2

37. India Plans to Hoist Tricolour on Moon by 2020. 4 January 2009. Hindustan Times. Retrieved from http://www.hindustantimes.com/india/india-plans-to-hoist-tricolour-on-moon-by-2020/story-kBha7UjIAPsXlPqTAlOK7H.html

38. During the 1960s, the US and USSR publicly denied there was a race to Moon at the time. Subsequent declassified documents leave no doubt that there was, in fact, a race. Similarly, today India is in a race with China. Even though India got to Mars before China, in pretty much every other respect, China’s space programme is well ahead of India’s. The report below reveals how India chose to go to Mars only after China’s attempt had failed: http://zeenews.india.com/news/sci-tech/a-book-that-reveals-indias-journey-to-mars-and-beyond_1500017.html

39. USA International Business Publications (Ed). 2011. India Space Programs and Exploration Handbook. Int’l Business Publications. P125. See also media reports from the time, for example, The Economic Times article ISRO, Russian Space Agency Join Hands for Indian Man Mission (http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2008-12-13/news/27728784_1_moon-mission-human-space-flight-isro).

40. The following piece suggests that India probably could not agree to the price Russia put on the technology transfer. During the “USSR days”, India benefited from many free and very favourable deals. Post USSR days and presence of financially savvy Russian protagonists, favourable deals were no longer on the table for India. See http://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/science/india-has-not-made-offer-to-russia-to-buy-soyuztma-isro/article369235.ece

41. PTI. 28 December 2012. IAF Developing Parameters for India’s Manned Space Mission. The Economic Times. Retrieved from http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/iaf-developing-parameters-for-indias-manned-space-mission/articleshow/17798420.cms?intenttarget=no

42. Also, ISRO had concluded that India (like other nations) would select future astronauts with test pilot experience, so the IAF would be the primary source.

43. For ISRO’s press release, see http://www.isro.gov.in/update/31-deCE-2013/media-reports-manned-mission-to-moon

44. The short but full statement is available here: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/erelease.aspx?relid=81367

45. The project director of India’s HSF is S. Unnikrishnan. He was also the payload director for the 2014 Crew Module Atmospheric Re-entry Experiment. He describes the state of the HSF programme in section 8.10 entitled Initiatives on Indian Human Space Flight in the following publication: ISRO. 2015. From Fishing Hamlet to Red Planet: India’s Space Journey. Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India: Harper Collins India.

46. An early design of a space suit that ISRO may use is based on the original Sokol space suits designed by the USSR in 1970. The current proposal for the Indian spacesuit is a modern version from Russia. For more information on this early version of the spacesuit, see http://danielmarin.naukas.com/2013/04/30/el-nuevo-traje-espacial-indio-que-en-realidad-es-ruso/. For the space food menu, ISRO has engaged the same company that supplied the food for Sharma’s spaceflight in 1984.

47. This free return option relies on air drag slowing down the spacecraft in Low Earth orbit. After about a week, the speed loss would result in an automatic re-entry and a splash-down provided the crew onboard has sufficient supplies to survive that long. This precautionary approach was designed for Yuri Gagarin’s historic 12 April 1961 spaceflight. However, Gagarin was launched into a higher than planned orbit. Re-entry would have occurred long after all the supplies were depleted.

48. Most rockets generate thrust at the bottom and “push” the payload. A Capsule Abort System “pulls” the crew capsule from the top. In the event of a fuel leak at the launch pad or an imminent explosion during the early phase of launch, the CAS, like an ejector seat, removes the crew capsule from the primary launch vehicle at high speed. This YouTube clip shows the CAS saving the crew of Soyuz T-10-1 in 1983: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UyFF4cpMVag

49. Even before the Space Age, a variety of insects and animals had made the journey to test rockets, and some even made it to space. In 1935, Stephen Smith in India transported a small cock and a hen about 800 m across a river by a rocket. Immediately after the World War II, the US tested V2 rockets brought from Germany to the US using mice, monkeys and dogs. A monkey called Yorick and 11 mice were the first to survive a trip to space in September 1951. The first dogs to enter space were launched from Kapustin Yar in 1951(see ‘Leading the Way: Soviet Space Dogs’. Accessed 8 August 2017. http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/visitmuseum/Plan_your_visit/exhibitions/cosmonauts/race-to-space/soviet-space-dogs). Many human lives have been lost in the pursuit of HSF since 1961, but not as many, had animals not been used. The first life forms to circle the Moon were turtles, wine flies, mealworms, plants, bacteria and other living matter in the USSR’s Zond 5 spacecraft. It was launched on a free return orbit to the Moon in September 1968. For an interesting summary of animals used in space launch systems, see http://history.nasa.gov/animals.html. For the guinea pigs used in the Chinese space programme, see http://edition.cnn.com/2003/TECH/space/10/03/china.space.timeline/

50. A DOS audit report highlights the delays and cost overruns arising from the SRE-2: http://www.cag.gov.in/sites/default/files/audit_report_files/Union_Compliance_Comptroller_Auditor_General_27_2014_chap_4.pdf

51. ISRO. 2015. From Fishing Hamlet to Red Planet: India’s Space Journey. Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India: Harper Collins India. P496

52. The initial announcement indicated that the Rakesh Sharma will be played by one of Bollywood’s leading actors, Amir Khan. Since then who will play the central role has become a little unclear. http://www.deccanchronicle.com/entertainment/bollywood/300617/confirmed-aamir-khan-to-star-in-astronaut-rakesh-sharmas-biopic.html

53. A public statement from her husband available herehttps://www.quora.com/Is-a-film-on-Kalpana-Chawla-being-made