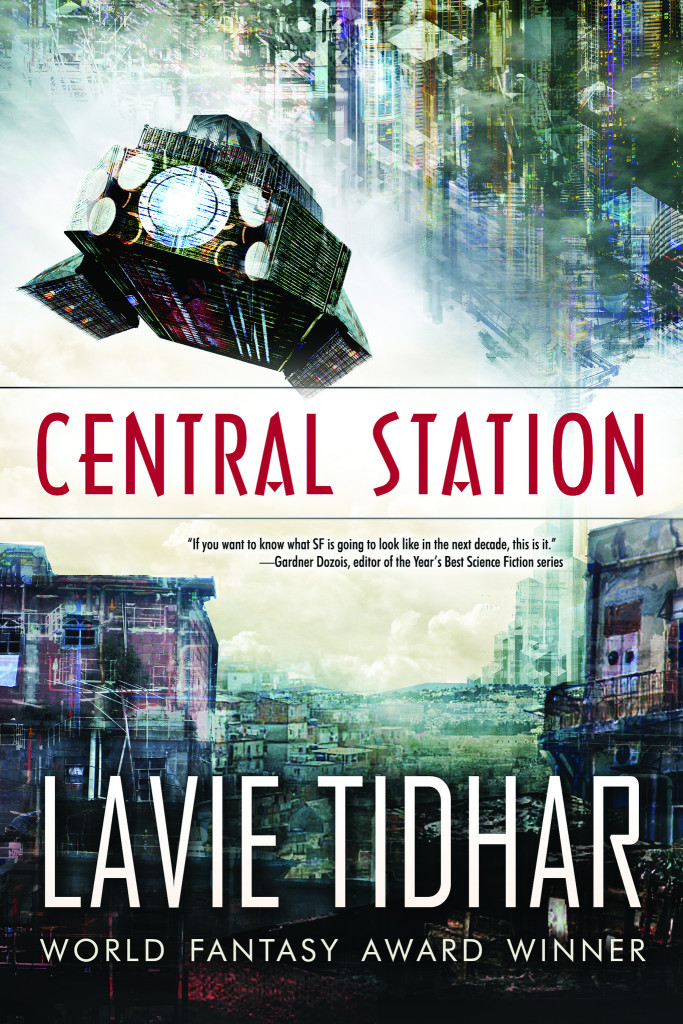

Lavie Tidhar is the author of the Jerwood Fiction Uncovered Prize winning and Premio Roma nominee A Man Lies Dreaming (2014), the World Fantasy Award winning Osama (2011) and of the critically-acclaimed The Violent Century (2013). His latest novel is Central Station (2016). He is the author of many other novels, novellas and short stories. His website is at http://lavietidhar.wordpress.com and he can be found on Twitter:@lavietidhar.

Central Station by Lavie Tidhar | Goodreads

Central Station pays homage to a bygone era of science fiction. You said its influences include seminal classics: Clifford Simak’s Project Pope (1981), Cordwainer Smith’s Norstrilia (1975), C.L. Moore’s Shambleau (1953), Philip K. Dick’s Ubik(1969), Zenna Henderson’s Pilgrimage (1961). When did you first start building Central Station as a massive spaceport, a border town in the middle of Israel and Palestine? Did you set out to write a mosaic novel from the beginning?

I started writing the wider world — the “future history” — where Central Station is set, years ago. But the novel — and yes, it was always planned as a mosaic novel! — started for me when I was living briefly back in Israel in 2010-2011. I became fascinated by Tel Aviv’s Central Bus Station area, which is much as described here, and by the people living there. I’ve always wanted to write a mosaic novel, though I was never quite sure how one goes about it. Some of my favourite science fiction novels when I was growing up were done in this way — City, Lord of Light, or pretty much anything by Cordwainer Smith, who to me is maybe one of the two or three most important American SF writers of the 20th century. And I like short stories, obviously, as a writer. So to me it was a technical challenge, in part — how do I write these more-or-less self-contained chapters/stories, that still add up to a bigger whole? But it allowed me to work on it, on and off, as I was working on “proper” novels. So I started it in Israel and then worked on it in London through the next several years. All this time I was writing books like The Violent Century and A Man Lies Dreaming. And of course working on other stories and so on. But to my delight theCentral Station stories started to sell, and were picked up for various Year’s Bests anthologies and so on. So that was nice. But it was my weird little passion project! I didn’t really expect anyone to end up publishing it, or for people to actually, you know, pick it up! So I’m still in a bit of a shock.

I think it does, you know, play with a lot of the older kind of science fiction, it corresponds with it. But it does it from an outsider’s perspective. From someone who was very obviously not included in those American SF stories. The other major influence on it, I think, is very different — it’s V.S. Naipaul’s Miguel Street. I wanted to write a story that wasn’t at all based on the pulp formula, on action, adventure, violence. My other novels are very interested in violence and plot. What I wanted was to write sort of slice-of-life science fiction. Domestic science fiction. About people who are just people, even if they live against the big shiny science fictional future.

So it’s been… on a personal level it was very satisfying to work on, and then for Tachyon to pick it up, and for people to seem to so far respond pretty well to it, that’s very rewarding — if, as I said, more than a little surprising to me!

Central Station is what science fiction is going to look like in the next decade, Gardner Dozois said. Where do think contemporary science fiction is today? In what direction some of your favorite contemporary books and authors are pushing the field?

Well, it was very kind of Gardner to say that. You’d have to ask him what he meant! I think, one of the exciting shifts we’re seeing in science fiction is the trickle of voices from outside of the Anglophone sphere into it. That different perspective. That’s something that never existed before. That’s exciting. We see it more obviously in short fiction at the moment, but we’re also seeing a lot more novels coming in. I don’t necessarily mean in translation, though certainly some of my favorite recent weirdnovels were translations, but also the choice to write in English if we want to.

I don’t know. My preference is for more off-beat, weird books, so I don’t feel that much connected to the mainstream of genre fiction, necessarily. I thought Saad Z. Hossain’s Escape From Baghdad! was fantastic, for example. Pasi Ilmari Jääskeläinen’s Rabbit Back Literature Society. More recently I was surprised and delighted by Zen Cho’s Sorcerer To The Crown, which is much more of a commercial sort of book but man, was it fun! I kind of started the first page and then found myself still reading at 2 in the morning. And, you know, pick up any one of the Apex Book of World SF volumes and you’ll find writers I’d be hugely excited about.

Are there other stories set in the world of Central Station that wasn’t included in the book? If yes, which ones? I can’t wait to read what happens next to Boris Chong and Kranki, or the bookseller cut off from the Conversation — and the data vampire, of course. The stories in the book are spellbinding, mesmerizing. I hated how Boris’s father chose his death because it almost broke my heart. But it was perhaps the best way for him to embrace that good night. How are you planning to write and publish new stories set in this universe—separately as before, or as a complete novel?

Thank you for saying that!

There is one Central Station story that got dropped from the final novel (“Crabapple”) but we’re going to include it as a bonus in the limited edition (and it’s available online). And there are about 28, I think, stories set in the wider universe outside of it. They were published over more than a decade, if you can believe it! But having written the last chapter of Central Station, I felt very strongly that I was done. In fact, I couldn’t write any more science fiction after that for about two years. I could only write in that genre again if I could find something new to say, and it was only when I was in Korea on a writing retreat that it finally clicked for me what I wanted to say. I was very inspired by the work of the great Korean novelist Pak Kyongni. So the next SF project I’m working on is very different. It brings different concerns, a different philosophy into it. You can find the first… taste of it in the recent Drowned Worlds anthology edited by Jonathan Strahan. With a couple more stories already sold. And then there are some exciting possibilities for me to do more in this new universe, but we’re still ironing out the details! I’m really looking forward to it.

The Apex Book of World SF series on Goodreads

You edited three World SF anthologies for Apex, and then helped Mahvesh Murad take it over recently. The critical response to the series has been great. How are these books doing commercially? How open and diverse is the world of SF—readers, writers, editors, publishers—today than when you started the World SF Blog in 2009?

Well, it’s not a commercial venture. I remember when I pitched it to Jason (our long-suffering publisher), it was something along the lines of “Look, no one’s going to actually buy it, but it’s an important book to do!” And Jason, happily, agreed with me.

It’s… the books are basically a showcase. A snapshot of the field in a particular time and place. They’re taught at university now. With every volume, we just hope to make enough to allow us to do another one. It’s a shoestring operation. But it’s very satisfying. It’s a lot of work! I think you’ll also note that a lot of the writers we featured early on went on to sell novels, win prizes — if you really want to see the future of genre fiction, like I said above, look at the Apex Book of World SF and you’ll see the rising stars of the future. When I started the World SF Blog, it was to try and push that conversation, and when I finished it four years later I felt that it had moved on tremendously since.

The thing is, I’m a writer predominantly. I didn’t want to become “that World SF guy”. And the other thing is, diversity can only really work if the editors themselves change. So after 3 volumes, I felt there was a need for me to step away, to let a different sensibility take over. I’m still very much involved, I remain as series editor, I handle all the messy stuff — paperwork, getting hold of reading material — but I don’t choose the stories. I think Mahvesh did a great job — I hope we can go on to do a Vol. 5 and, you know, in all honesty, I’d love it if we could keep doing them. The only rules I apply are, we never repeat writers, and we feature up to 2 authors per country per volume. Also I’d try and suggest, you know, areas we still haven’t covered. I keep a close eye on what’s coming out, I always look out for interesting new writers, for what’s being published, so that I have it to hand for later. It’s challenging, but it’s also very satisfying.

With its diverse cast and themes, do you see Central Station as an extension of your World SF project in spirit?

That’s an interesting question! I don’t think so as such — what I did take from it, in a very real way, was a sense around 2010 or so that I needed to stop telling other people’s stories and tell my stories. By which I mean, write about the people and the culture and the things I know about, my own background. And that very much came out of that wider conversation I think. But it’s a challenge, because what’s obvious and familiar to you may not be obvious and familiar to your readers. What I came to realize was that I needed to write for myself, to tell the stories that belonged to me. I’m not sure it makes for an easy life, necessarily. But it’s an interesting question! I never thought of it that way before. Maybe you’re right.

As a writer whose first language isn’t English, what are some of the challenges that you struggled with in your early career? How did you overcome them?

Well, I never saw it as a challenge, I saw it as an opportunity. One of the things I’ve tried very hard to do, for example, is keep my sense of rhythm, not to use “standard” English, necessarily, to keep my own voice. The biggest problem really was that for a while, the things I was trying to do were not necessarily the things American editors were looking for. I had to almost… make the case for what it was I was doing. But for a long time there were places essentially closed to me because of that. But I was very blessed that some terrific editors supported my work, like Ellen Datlow, who gave me my first big shot, or Gardner Dozois, who you mention above. I think speaking — and writing in — more than one language is incredibly important. At the moment, for instance, I’m writing a monthly column in Bislama, the South Pacific pidgin/creole spoken in Vanuatu. I write a short literary vignette a month, basically a short story of about 700-900 words, and it’s published in the monthly supplement of the Vanuatu Daily Post. This is tremendously exciting for me. It’s a great opportunity. And my first book was in fact a collection of Hebrew poetry. I only wish I spoke more languages. Usually I just pick up the very basics — how to shop in the market, in Lao, or how to swear in Afrikaans… both useful, depending on the circumstances, really!

Your new story, “Terminal,” is a shattering tale of migration to another world. What prompted you to write it? You have several new short stories coming out in 2016. How do you divide your time between short stories and novels?

“Terminal,” well, it was partly the whole “one way ticket to Mars” thing, and I wanted to kind of explore it in a more lyrical, more psychological way. What does it mean to leave everything behind?

The truth is, I love short stories. If it were up to me I’d only be writing short stories. I’m not really a novelist — I always get funny looks when I say it (“Just how many novels did you write, Lavie?”) but honestly I struggle with novels. Short stories feel much more natural to me. I don’t get to write them as much as I’d like, and especially novellas — I think I wrote a total of 7 novellas, which isn’t very much. It’s my favourite length. The last one just came out in F&SF — “The Vanishing Kind” — I really love that one.

Though as much as I love the immediacy of short stories, at some point I begin to long for a slower rhythm, which is when novels begin to take shape. When you work out one tiny piece of the puzzle at a time, and it’s a matter of months, not days. But I am a restless writer, so I’ll often be working on several things, and switch between them if I’m stuck on one or need a break.

At the moment I’ve got stories coming out in Apex, Analog, Tor.com and in Conjunctions, plus a few anthologies, and hopefully some new novels soon! I try to keep busy.

What is The Jewish Mexican Literary Review about? What made you start it?

The Jewish Mexican Literary Review really started as a joke between me and Silvia Moreno-Garcia. We were chatting about respectability, and then tried to come up with the most “respectable” name we could for a literary magazine. We figured you couldn’t go wrong with “literary” and “review” in the title, and “Jewish Mexican” was just us!

So then the joke was if we do one we could then legitimately say we’re “editors of the Jewish Mexican Literary Review”, which sounds really posh in an author bio. But of course that’s all it remained… until Silvia found the artwork by Jason Wright, that was so perfect for the title, and she made a mock-up cover, and at that point I said, Well, you realise now we have to do it!

So then we did. It was surprisingly stress free! Our whole attitude was, let’s be complete slackers about this. And ask people we like to send us whatever weird stuff they had, we were quite happy to take anything. So we ended up with a really eclectic, fun mix! I think we’re both really happy with it. We both have that focus on international diversity, and we loved the idea of running stories in more than one language. So we have Spanish there, we have Hebrew… Naomi Alderman wrote us a story especially for the magazine, recounting twin visits to Israel and Mexico. It was fantastic! It was a lot of fun to do. I’m kind of trying to convince Silvia we should do another one…